4.1. Речевые ошибки

В психолингвистике накоплен огромный

материал, связанный с ошибками в

производстве и восприятии речи (speech

errors).

К числу речевых ошибок относятся паузы

(они составляют до 40-50% речи), колебания,

исправления, повторы и замещения, а

также оговорки. Различают следующие

типы оговорок: подстановка, перестановка,

опущение, добавление.

Оговорки на фонологическом уровне

связаны преимущественно с заменой

первых и последних звуков находящихся

рядом слов (1) (причем первые меняются

на первые, последние на последние), с

заменой гласных и согласных; с

предвосхищением, пропуском и повтором

слогов.

(1) молодой человек > челодой моловек

Нередко также происходит оглушение или

озвончение согласных, появление или

пропадание фонологических признаков,

характерных для определенного языка

(например, назальности). Например, вместо

словосочетания clear blue sky может

прозвучать glear plue sky, где перестановке

подверглись различительные признаки

(-звонкий) в слове clear и (+звонкий) в

слове blue. При этом каждая ошибка

проявляется только в фонологически

возможном для данного языка контексте

с учетом грамматики данного языка.

Часто в речи встречается пропуск и

замена слогов, неправильное ударение,

а также перестановка слов (2); 87% ошибок

происходит в одних и тех же частях речи.

(2) Нельзя ли у вокзала трамвай остановить?

> Нельзя ли у трамвала вокзай остановить?

Повторы в 90% случаев приходятся на

служебные части речи вроде предлогов,

союзов и местоимений; исправлениям же

подвергаются в основном знаменательные

части речи — существительные, глаголы,

прилагательные и наречия.

На появление ошибок в речи влияют и

экстралингвистические факторы. Так,

человеку, начавшему говорить, может

попасться на глаза название книги:

(3) Target: «Are

you trying to send me a message, Dog?»

Situation: «A

novel of intrigue and menace»

Output: «Are you

trying to send me a menace, Dog?»

Описки, отличающиеся от орфографических

ошибок, понимаются как нестандартные

ошибки, возникающие при письме. На

принципе фонологического озвучивания

пишущегося слова основано 20% описок

(there / their). Значительно меньше ошибок,

вызванных графическим сходством букв

(there / theme). Встречаются также пропуски

(vsual < visual), перестановки (colsed <

closed) и добавления (bothe < both) букв.

Описки на морфемном уровне также содержат

в себе пропуски (went to <the> room) и

добавления (saw the the movement).

Ослышки могут быть связаны с недослышкой

как звуков в пределах одного слова (икра

> игра), так и сочетаний звуков между

словами и переразложением слов.

Оговорки и ослышки часто лежат в основе

шуток и анекдотов (4).

(4) — Ты кто такой? — Я прозаик.

— Про каких таких заек?

Ошибки речи подтверждают правомерность

выделения таких уровней языка, как

фонологический, морфологический,

просодический, семантический,

синтаксический и доказывают тот факт,

что при порождении речи человек оперирует

единицами этих уровней.

4.2. Стохастическая модель порождения речи

Дж.Миллер и Н.Хомский исходили из того,

что язык может быть описан как конечное

число состояний. И, следовательно, речь

можно описывать как такую последовательность

элементов, где появление каждого нового

элемента речевой цепи зависит от наличия

и вероятности появления предшествующих

элементов. Согласно этой теории, чтобы

обучиться порождать речь последовательно

(«слева направо»), ребенок должен

прослушать огромное количество — 2.100

предложений на родном языке, прежде чем

сам сможет порождать высказывания. Но

очевидно, что для этого не хватит и

десяти жизней.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Слайд 1Понятие и виды речевых ошибок в психолингвистике

Презентацию подготовила: студентка

2_КОЛ_ИПР

Москвичева Светлана Геннадьевна

ГОУ ВПО ЛНР «ЛУГАНСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ

ИМЕНИ

ТАРАСА ШЕВЧЕНКО

КАФЕДРА ДЕФЕКТОЛОГИИ И ПСИХОЛОГИЧЕСКОЙ КОРРЕКЦИИ

Слайд 2Речь – это канал развития интеллекта, чем раньше будет

усвоен язык, тем легче и полнее будут усваиваться знания.

Николай Иванович

Жинкин,

советский лингвист и психолог

Слайд 3Речевая ошибка — ошибка, связанная с неверным или не

с самым удачным употреблением слов или фразеологизмов.

Речевая ошибка — это

отклонение от литературной нормы.

Речевые ошибки зачастую рассматриваются только в лингвистическом контексте, но это весьма ошибочно, т.к. природа ошибки может быть различна и нести различный характер. В рамках психолингвистики существует достаточно много подходов и классификаций речевых ошибок. Так, еще в 1895 г. Мерингер, которого считают «отцом» проблемы речевых ошибок, опубликовал список из более 8000 ошибок в устной и письменной речи, а также ошибок, допускаемых при чтении.

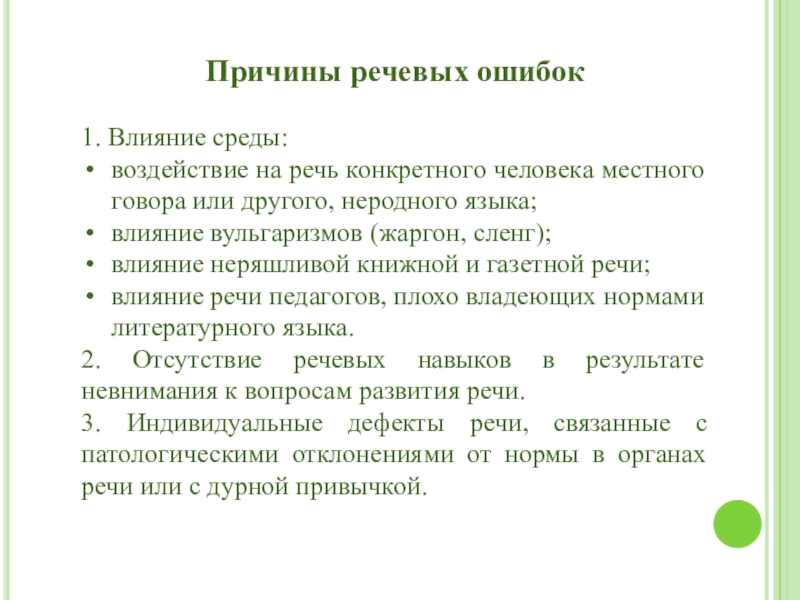

Слайд 4Причины речевых ошибок

1. Влияние среды:

воздействие на речь конкретного человека

местного говора или другого, неродного языка;

влияние вульгаризмов (жаргон, сленг);

влияние неряшливой

книжной и газетной речи;

влияние речи педагогов, плохо владеющих нормами литературного языка.

2. Отсутствие речевых навыков в результате невнимания к вопросам развития речи.

3. Индивидуальные дефекты речи, связанные с патологическими отклонениями от нормы в органах речи или с дурной привычкой.

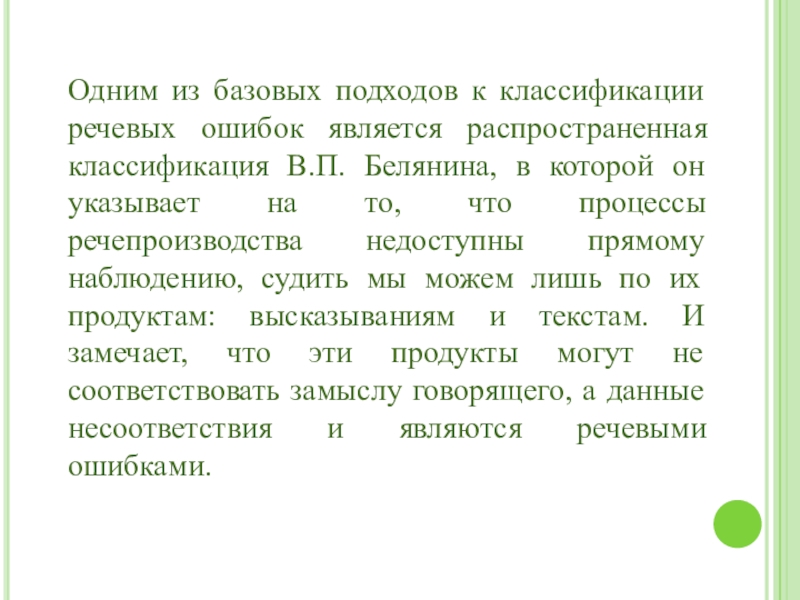

Слайд 5Одним из базовых подходов к классификации речевых ошибок является

распространенная классификация В.П. Белянина, в которой он указывает на то,

что процессы речепроизводства недоступны прямому наблюдению, судить мы можем лишь по их продуктам: высказываниям и текстам. И замечает, что эти продукты могут не соответствовать замыслу говорящего, а данные несоответствия и являются речевыми ошибками.

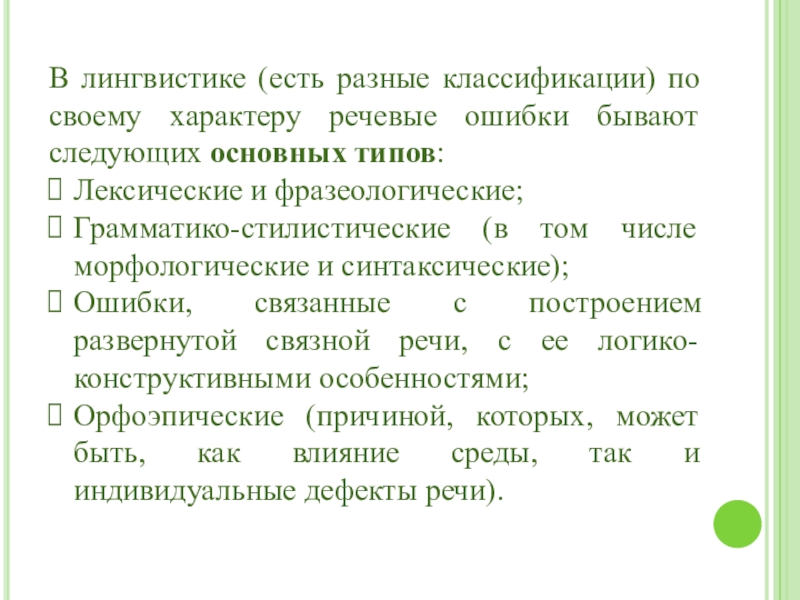

Слайд 6В лингвистике (есть разные классификации) по своему характеру речевые

ошибки бывают следующих основных типов:

Лексические и фразеологические;

Грамматико-стилистические (в том числе

морфологические и синтаксические);

Ошибки, связанные с построением развернутой связной речи, с ее логико-конструктивными особенностями;

Орфоэпические (причиной, которых, может быть, как влияние среды, так и индивидуальные дефекты речи).

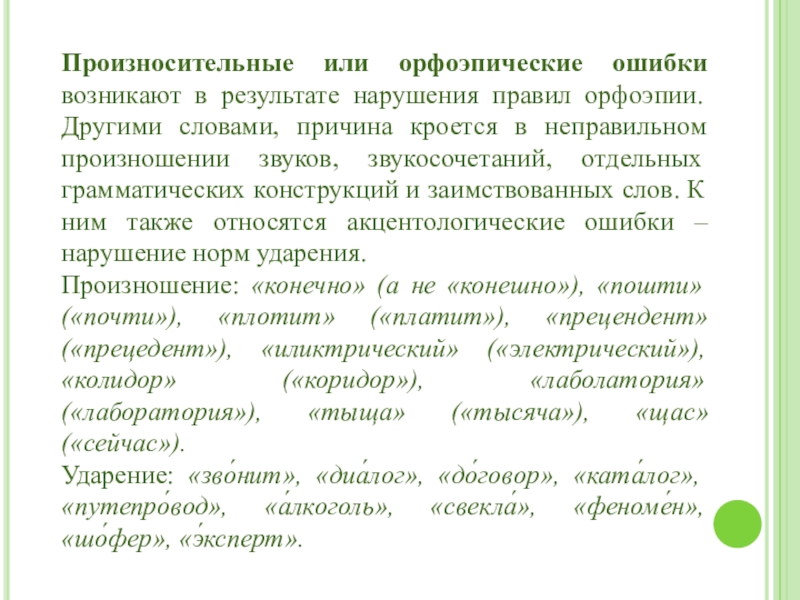

Слайд 7Произносительные или орфоэпические ошибки возникают в результате нарушения правил

орфоэпии. Другими словами, причина кроется в неправильном произношении звуков, звукосочетаний,

отдельных грамматических конструкций и заимствованных слов. К ним также относятся акцентологические ошибки – нарушение норм ударения.

Произношение: «конечно» (а не «конешно»), «пошти» («почти»), «плотит» («платит»), «прецендент» («прецедент»), «иликтрический» («электрический»), «колидор» («коридор»), «лаболатория» («лаборатория»), «тыща» («тысяча»), «щас» («сейчас»).

Ударение: «зво́нит», «диа́лог», «до́говор», «ката́лог», «путепро́вод», «а́лкоголь», «свекла́», «феноме́н», «шо́фер», «э́ксперт».

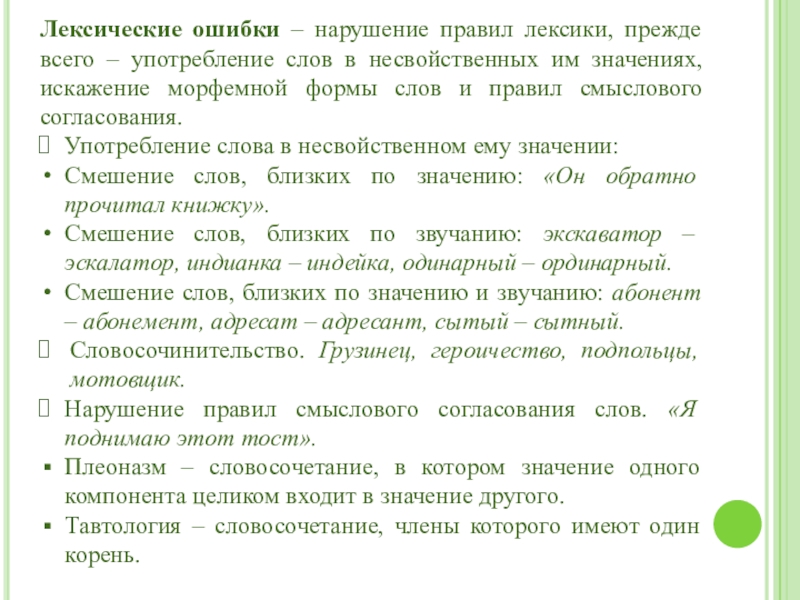

Слайд 8Лексические ошибки – нарушение правил лексики, прежде всего –

употребление слов в несвойственных им значениях, искажение морфемной формы слов

и правил смыслового согласования.

Употребление слова в несвойственном ему значении:

Смешение слов, близких по значению: «Он обратно прочитал книжку».

Смешение слов, близких по звучанию: экскаватор – эскалатор, индианка – индейка, одинарный – ординарный.

Смешение слов, близких по значению и звучанию: абонент – абонемент, адресат – адресант, сытый – сытный.

Словосочинительство. Грузинец, героичество, подпольцы, мотовщик.

Нарушение правил смыслового согласования слов. «Я поднимаю этот тост».

Плеоназм – словосочетание, в котором значение одного компонента целиком входит в значение другого.

Тавтология – словосочетание, члены которого имеют один корень.

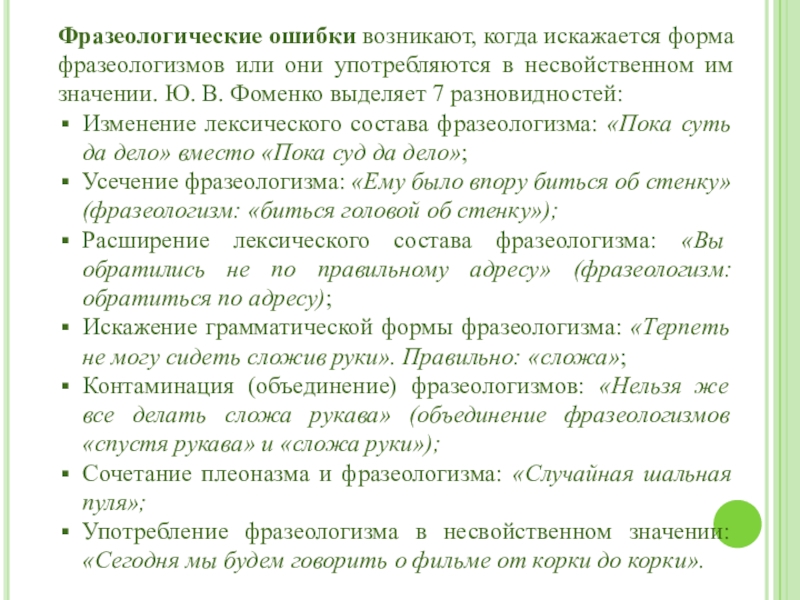

Слайд 9Фразеологические ошибки возникают, когда искажается форма фразеологизмов или они

употребляются в несвойственном им значении. Ю. В. Фоменко выделяет 7

разновидностей:

Изменение лексического состава фразеологизма: «Пока суть да дело» вместо «Пока суд да дело»;

Усечение фразеологизма: «Ему было впору биться об стенку» (фразеологизм: «биться головой об стенку»);

Расширение лексического состава фразеологизма: «Вы обратились не по правильному адресу» (фразеологизм: обратиться по адресу);

Искажение грамматической формы фразеологизма: «Терпеть не могу сидеть сложив руки». Правильно: «сложа»;

Контаминация (объединение) фразеологизмов: «Нельзя же все делать сложа рукава» (объединение фразеологизмов «спустя рукава» и «сложа руки»);

Сочетание плеоназма и фразеологизма: «Случайная шальная пуля»;

Употребление фразеологизма в несвойственном значении: «Сегодня мы будем говорить о фильме от корки до корки».

Слайд 10Морфологические ошибки – неправильное образование форм слова.

Примеры таких

речевых ошибок: «плацкарт», «туфель», «полотенцев», «дешевше», «в полуторастах километрах».

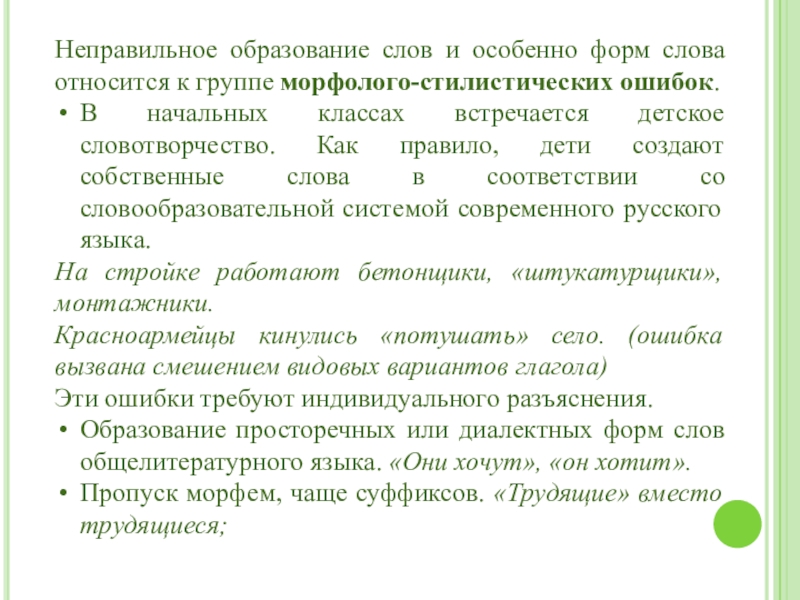

Слайд 11Неправильное образование слов и особенно форм слова относится к

группе морфолого-стилистических ошибок.

В начальных классах встречается детское словотворчество. Как правило,

дети создают собственные слова в соответствии со словообразовательной системой современного русского языка.

На стройке работают бетонщики, «штукатурщики», монтажники.

Красноармейцы кинулись «потушать» село. (ошибка вызвана смешением видовых вариантов глагола)

Эти ошибки требуют индивидуального разъяснения.

Образование просторечных или диалектных форм слов общелитературного языка. «Они хочут», «он хотит».

Пропуск морфем, чаще суффиксов. «Трудящие» вместо трудящиеся;

Слайд 12Синтаксические ошибки связаны с нарушением правил синтаксиса – конструирования

предложений, правил сочетания слов.

Неправильное согласование: «В шкафу стоят много

книг»;

Неправильное управление: «Оплачивайте за проезд»;

Синтаксическая двузначность: «Чтение Маяковского произвело сильное впечатление» (читал Маяковский или читали произведения Маяковского?);

Смещение конструкции: «Первое, о чём я вас прошу, – это о внимании». Правильно: «Первое, о чём я вас прошу, – это внимание»;

Лишнее соотносительное слово в главном предложении: «Мы смотрели на те звёзды, которые усеяли всё небо».

Слайд 13Среди допускаемых ошибок встречаются ошибки в словосочетаниях и предложениях

– синтаксисо- стилистические. Они очень многообразны.

Нарушение норм согласования и

управления – нарушение управления, чаще всего предложного:

Смеялись «с него». ( под влиянием диалектного – над ним).

Нарушение согласования, чаще всего сказуемого с подлежащим:

Саше очень «понравилось» ёлка. «Вся семья» радостно «встретили» Новый год.

Глагольное управление дети усваивают по образцам, в живой речи, в читаемых текстах. Поэтому ошибки в управлении могут быть предупреждены на основе анализа образцов и составления словосочетаний.

Слайд 14Орфографические ошибки возникают из-за незнания правил написания, переноса, сокращения

слов. Характерен для письменной речи. Например: «сабака лаяла», «сидеть на

стули», «приехать на вогзал», «русск. язык», «грамм. ошибка».

Пунктуационные ошибки – неправильное употребление знаков препинания при письме.

Слайд 15К речевым ошибкам относят: паузы, колебания, исправления, повторы и

замещения, а также оговорки.

Оговорки на фонологическом уровне связаны преимущественно с

подстановкой — заменой первых и последних звуков находящихся рядом слов. Различаются предвосхищение звука, который имеется позднее, и повторение звука, который был уже произнесен. Ещё чаще встречается замена одного слога на другой.

Оговорки подчиняются закону структурного деления слова на слоги. В частности, начальный слог слова, которое говорящий намеревается произнести, меняется на начальный слог другого слова, с которым происходит смешение; средний меняется на средний; последний меняется на последний (иное невозможно).

Слайд 16Возможно также оглушение или озвончение согласных, появление или пропадание

фонологических признаков, характерных для определённого языка. Если же говорящий предполагал

начать со звонкого согласного, а получился глухой, то можно говорить о предвосхищении признака глухости.

«Весёлая повесть – фесёлая повесть»

Одной из особенностей оговорок является то, что минимальный контроль за правильностью речи всё же сохраняется даже при производстве совсем невразумительного высказывания.

Возможно и неправильное ударение в словах.

К числу оговорок относят также сращения. Основываясь на замене, они возникают как случайное соединение двух близкорасположенных слов.

«Портмоне + манто – портмонто»

Слайд 17Описки в отличие от орфографических ошибок понимаются как нестандартные

ошибки, возникающие при письме. На принципе фонологического озвучивания пишущегося слова

(принцип «как слышится, так и пишется») основано 20% описок. Значительно меньше ошибок, вызванных графическим сходством букв. Встречаются также пропуски, перестановки и добавления букв. Описки на морфемном уровне также содержат в себе пропуски и добавления.

Слайд 18Особо также выделяются ошибки, основанные на замене двух сегментов

слов. Они известны под названием «спунеризмов» — слова, образованного от

имени декана одного из колледжей Оксфорда Вильяма Спунера.

Среди ошибок иногда выделяют неправильное словоупотребление. Такого рода ошибки называются малапропизмами от имени комической героини пьесы Шеридана «Соперники» мадам Малапроп, которая путала слова аллигатор и аллегория. Поскольку ряд исследователей пишет о зеркальности процесса порождения речи процессу её восприятия, в рамках проблемы речевых ошибок целесообразно рассмотреть и проблему ошибок восприятия речи.

Помимо описок, встречаются ошибки при восприятии речи: ослышки, «овидки», «очитки». Ослышки в речевой деятельности могут быть связаны с недослышкой как звуков в пределах одного слова (икра – игра), так и сочетаний звуков между словами и переразложением слов. При этом ослышки (-Ты кто такой? — Я писатель-прозаик. -Про каких таких заек?) и оговорки часто лежат в основе шуток и анекдотов.

Слайд 19Что касается пауз, то в речи они занимают до

40-50%, причем более половины из них приходится на естественные границы

грамматических отрезков (между синтагмами). Большинство речевых отрезков при этом не превышают объёма в шесть слов. При чтении бессистемных пауз меньше и они определяются синтаксическими структурами читаемого текста.

Слайд 20Многие речевые ошибки могут быть предупреждены в ходе изучения

грамматических форм. Для этого нужно уяснить, какие возможности открывает изучаемая

грамматическая форма для выражения оттенков мысли, для краткости и точности высказывания, для устранения возможных ошибок речи. Соответствующие моменты включаются в урок: школьники учатся исправлять недочеты речи на основе изучаемого материала грамматики.

Устранение речевых ошибок в связи с усвоением грамматического материала, не требуя почти нисколько дополнительного времени, не только повышает культуру речи учащихся, но и помогает им глубже усвоить грамматические понятия, подводит к осознанию роли изучаемых грамматических единиц в речи, в живом общении между людьми.

Слайд 21В целом речевые ошибки подтверждают правомерность выделения таких уровней

языка, как фонологический, морфологический, просодический, семантический, синтаксический, и доказывают тот

факт, что при производстве речи человек оперирует единицами этих уровней. Анализ ошибок свидетельствуют о необходимости комплексного психолингвистического подхода к функционированию языка у пользующегося им индивида.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A speech error, commonly referred to as a slip of the tongue[1] (Latin: lapsus linguae, or occasionally self-demonstratingly, lipsus languae) or misspeaking, is a deviation (conscious or unconscious) from the apparently intended form of an utterance.[2] They can be subdivided into spontaneously and inadvertently produced speech errors and intentionally produced word-plays or puns. Another distinction can be drawn between production and comprehension errors. Errors in speech production and perception are also called performance errors.[3] Some examples of speech error include sound exchange or sound anticipation errors. In sound exchange errors the order of two individual morphemes is reversed, while in sound anticipation errors a sound from a later syllable replaces one from an earlier syllable.[4] Slips of the tongue are a normal and common occurrence. One study shows that most people can make up to as much as 22 slips of the tongue per day.[5]

Speech errors are common among children, who have yet to refine their speech, and can frequently continue into adulthood. When errors continue past the age of 9 they are referred to as «residual speech errors» or RSEs.[6] They sometimes lead to embarrassment and betrayal of the speaker’s regional or ethnic origins. However, it is also common for them to enter the popular culture as a kind of linguistic «flavoring». Speech errors may be used intentionally for humorous effect, as with spoonerisms.

Within the field of psycholinguistics, speech errors fall under the category of language production. Types of speech errors include: exchange errors, perseveration, anticipation, shift, substitution, blends, additions, and deletions. The study of speech errors has contributed to the establishment/refinement of models of speech production since Victoria Fromkin’s pioneering work on this topic.[7]

Psycholinguistic explanations[edit]

Speech errors are made on an occasional basis by all speakers.[1] They occur more often when speakers are nervous, tired, anxious or intoxicated.[1] During live broadcasts on TV or on the radio, for example, nonprofessional speakers and even hosts often make speech errors because they are under stress.[1] Some speakers seem to be more prone to speech errors than others. For example, there is a certain connection between stuttering and speech errors.[8] Charles F. Hockett explains that «whenever a speaker feels some anxiety about possible lapse, he will be led to focus attention more than normally on what he has just said and on what he is just about to say. These are ideal breeding grounds for stuttering.»[8] Another example of a «chronic sufferer» is Reverend William Archibald Spooner, whose peculiar speech may be caused by a cerebral dysfunction, but there is much evidence that he invented his famous speech errors (spoonerisms).[1]

An explanation for the occurrence of speech errors comes from psychoanalysis, in the so-called Freudian slip. Sigmund Freud assumed that speech errors are the result of an intrapsychic conflict of concurrent intentions.[1] «Virtually all speech errors [are] caused by the intrusion of repressed ideas from the unconscious into one’s conscious speech output», Freud explained.[1] In fact, his hypothesis explains only a minority of speech errors.[1]

Psycholinguistic classification[edit]

There are few speech errors that clearly fall into only one category. The majority of speech errors can be interpreted in different ways and thus fall into more than one category.[9] For this reason, percentage figures for the different kinds of speech errors may be of limited accuracy.[10] Moreover, the study of speech errors gave rise to different terminologies and different ways of classifying speech errors. Here is a collection of the main types:

| Type | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | «Additions add linguistic material.»[1] | Target: We Error: We and I |

| Anticipation | «A later segment takes the place of an earlier segment.»[1] | Target: reading list Error: leading list |

| Blends | Blends are a subcategory of lexical selection errors.[10] More than one item is being considered during speech production. Consequently, the two intended items fuse together.[1] | Target: person/people Error: perple |

| Deletion | Deletions or omissions leave some linguistic material out.[1] | Target: unanimity of opinion Error: unamity of opinion |

| Exchange | Exchanges are double shifts. Two linguistic units change places.[1] | Target: getting your nose remodeled Error: getting your model renosed |

| Lexical selection error | The speaker has «problems with selecting the correct word».[10] | Target: tennis racquet Error: tennis bat |

| Malapropism, classical | The speaker has the wrong beliefs about the meaning of a word. Consequently, they produce the intended word, which is semantically inadequate. Therefore, this is a competence error rather than a performance error. Malapropisms are named after ‘Mrs. Malaprop’, a character from Richard B. Sheridan’s eighteenth-century play The Rivals.[3] | Target: The flood damage was so bad they had to evacuate the city. Error: The flood damage was so bad they had to evaporate the city. |

| Metathesis | «Switching of two sounds, each taking the place of the other.»[3] | Target: pus pocket Error: pos pucket |

| Morpheme-exchange error[10] | Morphemes change places. | Target: He has already packed two trunks. Error: He has already packs two trunked. |

| Morpheme stranding | Morphemes remain in place but are attached to the wrong words.[11] | Target: He has already packed two trunks. Error: He has already trunked two packs. |

| Omission | cf. deletions | Target: She can’t tell me. Error: She can tell me. |

| Perseveration | «An earlier segment replaces a later item.»[1] | Target: black boxes Error: black bloxes |

| Residual Speech Errors | «Distortions of late-developing sounds such as /s/, /l/, and /r/.»[6] | Target: The box is red.

Error: The box is wed. |

| Shift | «One speech segment disappears from its appropriate location and appears somewhere else.»[1] | Target: She decides to hit it. Error: She decide to hits it. |

| Sound-exchange error | Two sounds switch places.[10] | Target: Night life [nait laif] Error: Knife light [naif lait] |

| Spoonerism | A spoonerism is a kind of metathesis. Switching of initial sounds of two separate words.[3] They are named after Reverend William Archibald Spooner, who probably invented most of his famous spoonerisms.[10] | Target: I saw you light a fire. Error: I saw you fight a liar. |

| Substitution | One segment is replaced by an intruder. The source of the intrusion is not in the sentence.[1] | Target: Where is my tennis racquet? Error: Where is my tennis bat? |

| Word-exchange error | A word-exchange error is a subcategory of lexical selection errors.[10] Two words are switched. | Target: I must let the cat out of the house. Error: I must let the house out of the cat. |

Speech errors can affect different kinds of segments or linguistic units:

| Segment | Example |

|---|---|

| Distinctive or phonetic features | Target: clear blue sky Error: glear plue sky (voicing) |

| Phonemes or sounds | Target: ad hoc Error: odd hack |

| Sequences of sounds | Target: spoon feeding Error: foon speeding |

| Morphemes | Target: sure Error: unsure |

| Words | Target: I hereby deputize you. Error: I hereby jeopardize you. |

| Phrases | Target: The sun is shining./The sky is blue. Error: The sky is shining. |

Types[edit]

- Grammatical – For example, children take time to learn irregular verbs, so in English use the -ed form incorrectly. This is explored by Steven Pinker in his book Words and Rules.

- Mispronunciation

- Vocabulary – Young children make category approximations, using car for truck for example. This is known as hyponymy.

Examples[edit]

- «particuly» (particularly) ← elision

- «syntaxically» (syntactically) ← vocabulary

Scientific relevance[edit]

Speech production is a highly complex and extremely rapid process so that research into the involved mental mechanisms is very difficult.[10] Investigating the audible output of the speech production system is a way to understand these mental mechanisms. According to Gary S. Dell «the inner workings of a highly complex system are often revealed by the way in which the system breaks down».[10] Therefore, speech errors are of an explanatory value with regard to the nature of language and language production.[12]

Performance errors may provide the linguist with empirical evidence for linguistic theories and serve to test hypotheses about language and speech production models.[13] For that reason, the study of speech errors is significant for the construction of performance models and gives insight into language mechanisms.[13]

Evidence and insights[edit]

- Speech errors provide investigators with insights into the sequential order of language production processes.[10]

- Speech errors clue investigators in on the interactivity of language production modules.[12]

- The existence of lexical or phonemic exchange errors provides evidence that speakers typically engage in forward planning their utterances. It seems that before the speaker starts speaking the whole utterance is available.[10]

- Anticipation

- Target: Take my bike.

- Error: Bake my bike.

- Perseveration

- Target: He pulled a tantrum.

- Error: He pulled a pantrum.

- Performance errors supply evidence for the psychological existence of discrete linguistic units.

- Speech errors involve substitutions, shifts, additions and deletions of segments. «In order to move a sound, the speaker must think of it as a separate unit.»[3] Obviously, one cannot account for speech errors without speaking of these discrete segments. They constitute the planning units of language production.[1] Among them are distinctive features, phonemes, morphemes, syllables, words and phrases. Victoria Fromkin points out that «many of the segments that change and move in speech errors are precisely those postulated by linguistic theories.» Consequently, speech errors give evidence that these units are psychologically real.

- One can infer from speech errors that speakers adhere to a set of linguistic rules.

- «There is a complex set of rules which the language user follows when making use of these units.»[3] Among them are for example phonetic constraints, which prescribe the possible sequences of sounds.[3] Moreover, the study of speech error confirmed the existence of rules that state how morphemes are to be pronounced or how they should be combined with other morphemes.[3] The following examples show that speech errors also observe these rules:

-

- Target: He likes to have his team rested. [rest+id]

- Error: He likes to have his rest teamed. [ti:m+d]

-

- Target: Both kids are sick. [kid+z]

- Error: Both sicks are kids. [sik+s]

- Here the past tense morpheme resp. the plural morpheme is phonologically conditioned, although the lemmas are exchanged. This proves that first the lemmas are inserted and then phonological conditioning takes place.

-

- Target: Don’t yell so loud! / Don’t shout so loud!

- Error: Don’t shell so loud!

- «Shout» and «yell» are both appropriate words in this context. Due to the pressure to continue speaking, the speaker has to make a quick decision which word should be selected.[8] This pressure leads to the speaker’s attempt to utter the two words simultaneously, which resulted in the creation of a blend.[8] According to Charles F. Hockett there are six possible blends of «shout» and «yell».[8] Why did the speaker choose «shell» and not one of the alternatives? The speaker obeyed unconscious linguistic rules because he selected the blend, which satisfied the linguistic demands of these rules the best.[8] Illegal non-words are for example instantaneously rejected.

- In conclusion, the rules which tell language users how to produce speech must also be part of our mental organization of language.[3]

- Substitution errors, for instance, reveal parts of the organization and structure of the mental lexicon.

-

- Target: My thesis is too long.

- Error: My thesis is too short.

- In case of substitution errors both segments mostly belong to the same category, which means for example that a noun is substituted for a noun. Lexical selection errors are based on semantic relations such as synonymy, antonymy or membership of the same lexical field.[2] For this reason the mental lexicon is structured in terms of semantic relationships.[3]

-

- Target: George’s wife

- Error: George’s life

-

- Target: fashion square

- Error: passion square

- Some substitution errors which are based on phonological similarities supply evidence that the mental lexicon is also organized in terms of sound.[3]

- Errors in speech are non-random. Linguists can elicit from the speech error data how speech errors are produced and which linguistic rules they adhere to. As a result, they are able to predict speech errors.

- Four generalizations about speech errors have been identified:[1]

- Interacting elements tend to come from a similar linguistic environment, which means that initial, middle, final segments interact with one another.

- Elements that interact with one another tend to be phonetically or semantically similar to one another. This means that consonants exchange with consonants and vowels with vowels.

- Slips are consistent with the phonological rules of the language.

- There are consistent stress patterns in speech errors. Predominantly, both interacting segments receive major or minor stress.

- These four generalizations support the idea of the lexical bias effect. This effect states that our phonological speech errors generally form words rather than non-words. Baars (1975) showed evidence for this effect when he presented word pairs in rapid succession and asked participants to say both words in rapid succession back. In most of the trials, the mistakes made still formed actual words.[14]

Information obtained from performance additions[edit]

An example of the information that can be obtained is the use of «um» or «uh» in a conversation.[15] These might be meaningful words that tell different things, one of which is to hold a place in the conversation so as not to be interrupted. There seems to be a hesitant stage and fluent stage that suggest speech has different levels of production. The pauses seem to occur between sentences, conjunctional points and before the first content word in a sentence. That suggests that a large part of speech production happens there.

Schachter et al. (1991) conducted an experiment to examine if the numbers of word choices affect pausing. They sat in on the lectures of 47 undergraduate professors from 10 different departments and calculated the number and times of filled pauses and unfilled pauses. They found significantly more pauses in the humanities departments as opposed to the natural sciences.[16] These findings suggest that the greater the number of word choices, the more frequent are the pauses, and hence the pauses serve to allow us time to choose our words.

Slips of the tongue are another form of «errors» that can help us understand the process of speech production better. Slips can happen at many levels, at the syntactic level, at the phrasal level, at the lexical semantic level, at the morphological level and at the phonological level and they can take more than one form like: additions, substations, deletion, exchange, anticipation, perseveration, shifts, and haplologies M.F. Garrett, (1975).[17] Slips are orderly because language production is orderly.

There are some biases shown through slips of the tongue. One kind is a lexical bias which shows that the slips people generate are more often actual words than random sound strings. Baars Motley and Mackay (1975) found that it was more common for people to turn two actual words to two other actual words than when they do not create real words.[14] This suggests that lexemes might overlap somewhat or be stored similarly.

A second kind is a semantic bias which shows a tendency for sound bias to create words that are semantically related to other words in the linguistic environment. Motley and Baars (1976) found that a word pair like «get one» will more likely slip to «wet gun» if the pair before it is «damp rifle». These results suggest that we are sensitive to how things are laid out semantically.[18]

Euphemistic misspeaking[edit]

Since the 1980s, the word misspeaking has been used increasingly in politics to imply that errors made by a speaker are accidental and should not be construed as a deliberate attempt to misrepresent the facts of a case. As such, its usage has attracted a degree of media coverage, particularly from critics who feel that the term is overly approbative in cases where either ignorance of the facts or intent to misrepresent should not be discarded as possibilities.[19][20]

The word was used by a White House spokesman after George W. Bush seemed to say that his government was always «thinking about new ways to harm our country and our people» (a classic example of a Bushism), and more famously by then American presidential candidate Hillary Clinton who recalled landing in at the US military outpost of Tuzla «under sniper fire» (in fact, video footage demonstrates that there were no such problems on her arrival).[20][21] Other users of the term include American politician Richard Blumenthal, who incorrectly stated on a number of occasions that he had served in Vietnam during the Vietnam War.[20]

See also[edit]

- Error (linguistics)

- Auditory processing disorder

- Barbarism (grammar)

- Epenthesis

- Errors in early word use

- Folk etymology

- FOXP2

- Developmental verbal dyspraxia

- Malapropism

- Metathesis (linguistics)

- Signorelli parapraxis

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Carroll, David (1986). Psychology of language. Pacific Grove, CA, USA: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co. pp. 253–256. ISBN 978-0-534-05640-7. OCLC 12583436.

- ^ a b Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Routledge: London 1996, 449.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tserdanelis, Georgios; Wai Sum Wong (2004). Language files: materials for an introduction to language & linguistics. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. pp. 320–324. ISBN 978-0-8142-0970-7. OCLC 54503589.

- ^ Dell, Gary S.; Reich, Peter A. (December 1981). «Stages in sentence production: An analysis of speech error data». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 20 (6): 611–629. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(81)90202-4.

- ^ «Slips of the Tongue». Psychology Today. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ a b Preston, Jonathan; Byun, Tara (November 2015). «Residual Speech Errors: Causes, Implications, Treatment». Seminars in Speech and Language. 36 (4): 215–216. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1562904. ISSN 0734-0478. PMID 26458196.

- ^ Fromkin, Victoria. «The Non-Anomalous Nature of Anomalous Utterances» (PDF). Stanford.

- ^ a b c d e f Hockett, Charles F. (1973). «Where the tongue slips, there slip I». In Victoria Fromkin (ed.). Speech errors as linguistic evidence. The Hague: Mouton. pp. 97–114. OCLC 1009093.

- ^ Pfau, Roland. Grammar as processor: a distributed morphology account of spontaneous speech. John Benjamins Publishing Co.: Amsterdam 2009, 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Eysenck, Michael W.; Keane, Mark A. (2005). Cognitive Psychology: A Student’s Handbook. Psychology Press (UK). p. 402. ISBN 978-1-84169-359-0. OCLC 608153953.

- ^ Anderson, John R. Kognitive Psychologie. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Heidelberg 1996 (2nd edition), 353.

- ^ a b Smith, Derek J. «Speech Errors, Speech Production Models, and Speech Pathology.» Human Information Processing. Date of last revision: 12 December 2003. Date of access: 27 February 2010. «Speech-errors». Archived from the original on 5 December 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2007..

- ^ a b Fromkin, Victoria (1973). «Introduction». In Victoria Fromkin (ed.). Speech errors as linguistic evidence. The Hague: Mouton. p. 13. ISBN 978-90-279-2668-5. OCLC 1009093.

- ^ a b Baars, Bernard J.; Michael T. Motley; Donald G. MacKay (August 1975). «Output editing for lexical status in artificially elicited slips of the tongue». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 14 (4): 382–391. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(75)80017-X.

- ^ Clark HH, Fox Tree JE (May 2002). «Using uh and um in spontaneous speaking». Cognition. 84 (1): 73–111. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.5.7958. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(02)00017-3. PMID 12062148. S2CID 37642332.

- ^ Schachter, Stanley; Nicholas Christenfeld; Bernard Ravina; Frances Bilous (March 1991). «Speech Disfluency and the Structure of Knowledge». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 60 (3): 362–367. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.362.[dead link]

- ^ Garrett, M. F. (1975). «The analysis of sentence production.». In Gordon H Bower (ed.). The Psychology of learning and motivation. Volume 9 : advances in research and theory. New York: Academic Press. pp. 133–177. ISBN 978-0-12-543309-9. OCLC 24672687.

- ^ Motley, Michael T.; Bernard J. Baars (1976). «Semantic bias effects on the outcomes of verbal slips». Cognition. 43 (2): 177–187. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(76)90003-2. S2CID 53152698.[dead link]

- ^ Hendrik Hertzberg (21 April 2008). «Mr. and Ms. Spoken». The New Yorker. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Dominic Lawson (23 May 2010). «Don’t lie – try misspeaking instead». The Sunday Times. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ «Does ‘misspeak’ mean lying?». BBC News. 26 March 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

Further reading[edit]

- Bock, J. K. (1982). Toward a cognitive psychology of syntax. Psychological Review, 89, 1-47.

- Garrett, M. F. (1976). Syntactic processing in sentence production. In E. Walker & R. Wales (Eds.), New approaches to language mechanisms (pp. 231–256). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Garrett, M. F. (1980). Levels of processing in sentence production. In B. Butterworth (Ed.), Language production: Vol. 1. Speech and talk (pp. 177–220). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Hickok G (2012). «The cortical organization of speech processing: feedback control and predictive coding the context of a dual-stream model». J Commun Disord. 45 (6): 393–402. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2012.06.004. PMC 3468690. PMID 22766458.

- Jescheniak, J.D., Levelt, W.J.M (1994). Word Frequency Effects in Speech Production: Retrieval of Syntactic Information and of Phonological Form. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, Vol. 20, (pp. 824–843)

- Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Poeppel D, Emmorey K, Hickok G, Pylkkänen L (October 2012). «Towards a new neurobiology of language». J. Neurosci. 32 (41): 14125–31. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3244-12.2012. PMC 3495005. PMID 23055482.

- Reichman, R. (1981). Plain Speaking: A Theory and Grammar of Spontaneous Discourse. Cambridge, MA

- Bache, Richard Meade. (1869). Vulgarisms and Other Errors of Speech.

External links[edit]

- «Fromkins Speech Error Database — Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics». www.mpi.nl. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A speech error, commonly referred to as a slip of the tongue[1] (Latin: lapsus linguae, or occasionally self-demonstratingly, lipsus languae) or misspeaking, is a deviation (conscious or unconscious) from the apparently intended form of an utterance.[2] They can be subdivided into spontaneously and inadvertently produced speech errors and intentionally produced word-plays or puns. Another distinction can be drawn between production and comprehension errors. Errors in speech production and perception are also called performance errors.[3] Some examples of speech error include sound exchange or sound anticipation errors. In sound exchange errors the order of two individual morphemes is reversed, while in sound anticipation errors a sound from a later syllable replaces one from an earlier syllable.[4] Slips of the tongue are a normal and common occurrence. One study shows that most people can make up to as much as 22 slips of the tongue per day.[5]

Speech errors are common among children, who have yet to refine their speech, and can frequently continue into adulthood. When errors continue past the age of 9 they are referred to as «residual speech errors» or RSEs.[6] They sometimes lead to embarrassment and betrayal of the speaker’s regional or ethnic origins. However, it is also common for them to enter the popular culture as a kind of linguistic «flavoring». Speech errors may be used intentionally for humorous effect, as with spoonerisms.

Within the field of psycholinguistics, speech errors fall under the category of language production. Types of speech errors include: exchange errors, perseveration, anticipation, shift, substitution, blends, additions, and deletions. The study of speech errors has contributed to the establishment/refinement of models of speech production since Victoria Fromkin’s pioneering work on this topic.[7]

Psycholinguistic explanations[edit]

Speech errors are made on an occasional basis by all speakers.[1] They occur more often when speakers are nervous, tired, anxious or intoxicated.[1] During live broadcasts on TV or on the radio, for example, nonprofessional speakers and even hosts often make speech errors because they are under stress.[1] Some speakers seem to be more prone to speech errors than others. For example, there is a certain connection between stuttering and speech errors.[8] Charles F. Hockett explains that «whenever a speaker feels some anxiety about possible lapse, he will be led to focus attention more than normally on what he has just said and on what he is just about to say. These are ideal breeding grounds for stuttering.»[8] Another example of a «chronic sufferer» is Reverend William Archibald Spooner, whose peculiar speech may be caused by a cerebral dysfunction, but there is much evidence that he invented his famous speech errors (spoonerisms).[1]

An explanation for the occurrence of speech errors comes from psychoanalysis, in the so-called Freudian slip. Sigmund Freud assumed that speech errors are the result of an intrapsychic conflict of concurrent intentions.[1] «Virtually all speech errors [are] caused by the intrusion of repressed ideas from the unconscious into one’s conscious speech output», Freud explained.[1] In fact, his hypothesis explains only a minority of speech errors.[1]

Psycholinguistic classification[edit]

There are few speech errors that clearly fall into only one category. The majority of speech errors can be interpreted in different ways and thus fall into more than one category.[9] For this reason, percentage figures for the different kinds of speech errors may be of limited accuracy.[10] Moreover, the study of speech errors gave rise to different terminologies and different ways of classifying speech errors. Here is a collection of the main types:

| Type | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | «Additions add linguistic material.»[1] | Target: We Error: We and I |

| Anticipation | «A later segment takes the place of an earlier segment.»[1] | Target: reading list Error: leading list |

| Blends | Blends are a subcategory of lexical selection errors.[10] More than one item is being considered during speech production. Consequently, the two intended items fuse together.[1] | Target: person/people Error: perple |

| Deletion | Deletions or omissions leave some linguistic material out.[1] | Target: unanimity of opinion Error: unamity of opinion |

| Exchange | Exchanges are double shifts. Two linguistic units change places.[1] | Target: getting your nose remodeled Error: getting your model renosed |

| Lexical selection error | The speaker has «problems with selecting the correct word».[10] | Target: tennis racquet Error: tennis bat |

| Malapropism, classical | The speaker has the wrong beliefs about the meaning of a word. Consequently, they produce the intended word, which is semantically inadequate. Therefore, this is a competence error rather than a performance error. Malapropisms are named after ‘Mrs. Malaprop’, a character from Richard B. Sheridan’s eighteenth-century play The Rivals.[3] | Target: The flood damage was so bad they had to evacuate the city. Error: The flood damage was so bad they had to evaporate the city. |

| Metathesis | «Switching of two sounds, each taking the place of the other.»[3] | Target: pus pocket Error: pos pucket |

| Morpheme-exchange error[10] | Morphemes change places. | Target: He has already packed two trunks. Error: He has already packs two trunked. |

| Morpheme stranding | Morphemes remain in place but are attached to the wrong words.[11] | Target: He has already packed two trunks. Error: He has already trunked two packs. |

| Omission | cf. deletions | Target: She can’t tell me. Error: She can tell me. |

| Perseveration | «An earlier segment replaces a later item.»[1] | Target: black boxes Error: black bloxes |

| Residual Speech Errors | «Distortions of late-developing sounds such as /s/, /l/, and /r/.»[6] | Target: The box is red.

Error: The box is wed. |

| Shift | «One speech segment disappears from its appropriate location and appears somewhere else.»[1] | Target: She decides to hit it. Error: She decide to hits it. |

| Sound-exchange error | Two sounds switch places.[10] | Target: Night life [nait laif] Error: Knife light [naif lait] |

| Spoonerism | A spoonerism is a kind of metathesis. Switching of initial sounds of two separate words.[3] They are named after Reverend William Archibald Spooner, who probably invented most of his famous spoonerisms.[10] | Target: I saw you light a fire. Error: I saw you fight a liar. |

| Substitution | One segment is replaced by an intruder. The source of the intrusion is not in the sentence.[1] | Target: Where is my tennis racquet? Error: Where is my tennis bat? |

| Word-exchange error | A word-exchange error is a subcategory of lexical selection errors.[10] Two words are switched. | Target: I must let the cat out of the house. Error: I must let the house out of the cat. |

Speech errors can affect different kinds of segments or linguistic units:

| Segment | Example |

|---|---|

| Distinctive or phonetic features | Target: clear blue sky Error: glear plue sky (voicing) |

| Phonemes or sounds | Target: ad hoc Error: odd hack |

| Sequences of sounds | Target: spoon feeding Error: foon speeding |

| Morphemes | Target: sure Error: unsure |

| Words | Target: I hereby deputize you. Error: I hereby jeopardize you. |

| Phrases | Target: The sun is shining./The sky is blue. Error: The sky is shining. |

Types[edit]

- Grammatical – For example, children take time to learn irregular verbs, so in English use the -ed form incorrectly. This is explored by Steven Pinker in his book Words and Rules.

- Mispronunciation

- Vocabulary – Young children make category approximations, using car for truck for example. This is known as hyponymy.

Examples[edit]

- «particuly» (particularly) ← elision

- «syntaxically» (syntactically) ← vocabulary

Scientific relevance[edit]

Speech production is a highly complex and extremely rapid process so that research into the involved mental mechanisms is very difficult.[10] Investigating the audible output of the speech production system is a way to understand these mental mechanisms. According to Gary S. Dell «the inner workings of a highly complex system are often revealed by the way in which the system breaks down».[10] Therefore, speech errors are of an explanatory value with regard to the nature of language and language production.[12]

Performance errors may provide the linguist with empirical evidence for linguistic theories and serve to test hypotheses about language and speech production models.[13] For that reason, the study of speech errors is significant for the construction of performance models and gives insight into language mechanisms.[13]

Evidence and insights[edit]

- Speech errors provide investigators with insights into the sequential order of language production processes.[10]

- Speech errors clue investigators in on the interactivity of language production modules.[12]

- The existence of lexical or phonemic exchange errors provides evidence that speakers typically engage in forward planning their utterances. It seems that before the speaker starts speaking the whole utterance is available.[10]

- Anticipation

- Target: Take my bike.

- Error: Bake my bike.

- Perseveration

- Target: He pulled a tantrum.

- Error: He pulled a pantrum.

- Performance errors supply evidence for the psychological existence of discrete linguistic units.

- Speech errors involve substitutions, shifts, additions and deletions of segments. «In order to move a sound, the speaker must think of it as a separate unit.»[3] Obviously, one cannot account for speech errors without speaking of these discrete segments. They constitute the planning units of language production.[1] Among them are distinctive features, phonemes, morphemes, syllables, words and phrases. Victoria Fromkin points out that «many of the segments that change and move in speech errors are precisely those postulated by linguistic theories.» Consequently, speech errors give evidence that these units are psychologically real.

- One can infer from speech errors that speakers adhere to a set of linguistic rules.

- «There is a complex set of rules which the language user follows when making use of these units.»[3] Among them are for example phonetic constraints, which prescribe the possible sequences of sounds.[3] Moreover, the study of speech error confirmed the existence of rules that state how morphemes are to be pronounced or how they should be combined with other morphemes.[3] The following examples show that speech errors also observe these rules:

-

- Target: He likes to have his team rested. [rest+id]

- Error: He likes to have his rest teamed. [ti:m+d]

-

- Target: Both kids are sick. [kid+z]

- Error: Both sicks are kids. [sik+s]

- Here the past tense morpheme resp. the plural morpheme is phonologically conditioned, although the lemmas are exchanged. This proves that first the lemmas are inserted and then phonological conditioning takes place.

-

- Target: Don’t yell so loud! / Don’t shout so loud!

- Error: Don’t shell so loud!

- «Shout» and «yell» are both appropriate words in this context. Due to the pressure to continue speaking, the speaker has to make a quick decision which word should be selected.[8] This pressure leads to the speaker’s attempt to utter the two words simultaneously, which resulted in the creation of a blend.[8] According to Charles F. Hockett there are six possible blends of «shout» and «yell».[8] Why did the speaker choose «shell» and not one of the alternatives? The speaker obeyed unconscious linguistic rules because he selected the blend, which satisfied the linguistic demands of these rules the best.[8] Illegal non-words are for example instantaneously rejected.

- In conclusion, the rules which tell language users how to produce speech must also be part of our mental organization of language.[3]

- Substitution errors, for instance, reveal parts of the organization and structure of the mental lexicon.

-

- Target: My thesis is too long.

- Error: My thesis is too short.

- In case of substitution errors both segments mostly belong to the same category, which means for example that a noun is substituted for a noun. Lexical selection errors are based on semantic relations such as synonymy, antonymy or membership of the same lexical field.[2] For this reason the mental lexicon is structured in terms of semantic relationships.[3]

-

- Target: George’s wife

- Error: George’s life

-

- Target: fashion square

- Error: passion square

- Some substitution errors which are based on phonological similarities supply evidence that the mental lexicon is also organized in terms of sound.[3]

- Errors in speech are non-random. Linguists can elicit from the speech error data how speech errors are produced and which linguistic rules they adhere to. As a result, they are able to predict speech errors.

- Four generalizations about speech errors have been identified:[1]

- Interacting elements tend to come from a similar linguistic environment, which means that initial, middle, final segments interact with one another.

- Elements that interact with one another tend to be phonetically or semantically similar to one another. This means that consonants exchange with consonants and vowels with vowels.

- Slips are consistent with the phonological rules of the language.

- There are consistent stress patterns in speech errors. Predominantly, both interacting segments receive major or minor stress.

- These four generalizations support the idea of the lexical bias effect. This effect states that our phonological speech errors generally form words rather than non-words. Baars (1975) showed evidence for this effect when he presented word pairs in rapid succession and asked participants to say both words in rapid succession back. In most of the trials, the mistakes made still formed actual words.[14]

Information obtained from performance additions[edit]

An example of the information that can be obtained is the use of «um» or «uh» in a conversation.[15] These might be meaningful words that tell different things, one of which is to hold a place in the conversation so as not to be interrupted. There seems to be a hesitant stage and fluent stage that suggest speech has different levels of production. The pauses seem to occur between sentences, conjunctional points and before the first content word in a sentence. That suggests that a large part of speech production happens there.

Schachter et al. (1991) conducted an experiment to examine if the numbers of word choices affect pausing. They sat in on the lectures of 47 undergraduate professors from 10 different departments and calculated the number and times of filled pauses and unfilled pauses. They found significantly more pauses in the humanities departments as opposed to the natural sciences.[16] These findings suggest that the greater the number of word choices, the more frequent are the pauses, and hence the pauses serve to allow us time to choose our words.

Slips of the tongue are another form of «errors» that can help us understand the process of speech production better. Slips can happen at many levels, at the syntactic level, at the phrasal level, at the lexical semantic level, at the morphological level and at the phonological level and they can take more than one form like: additions, substations, deletion, exchange, anticipation, perseveration, shifts, and haplologies M.F. Garrett, (1975).[17] Slips are orderly because language production is orderly.

There are some biases shown through slips of the tongue. One kind is a lexical bias which shows that the slips people generate are more often actual words than random sound strings. Baars Motley and Mackay (1975) found that it was more common for people to turn two actual words to two other actual words than when they do not create real words.[14] This suggests that lexemes might overlap somewhat or be stored similarly.

A second kind is a semantic bias which shows a tendency for sound bias to create words that are semantically related to other words in the linguistic environment. Motley and Baars (1976) found that a word pair like «get one» will more likely slip to «wet gun» if the pair before it is «damp rifle». These results suggest that we are sensitive to how things are laid out semantically.[18]

Euphemistic misspeaking[edit]

Since the 1980s, the word misspeaking has been used increasingly in politics to imply that errors made by a speaker are accidental and should not be construed as a deliberate attempt to misrepresent the facts of a case. As such, its usage has attracted a degree of media coverage, particularly from critics who feel that the term is overly approbative in cases where either ignorance of the facts or intent to misrepresent should not be discarded as possibilities.[19][20]

The word was used by a White House spokesman after George W. Bush seemed to say that his government was always «thinking about new ways to harm our country and our people» (a classic example of a Bushism), and more famously by then American presidential candidate Hillary Clinton who recalled landing in at the US military outpost of Tuzla «under sniper fire» (in fact, video footage demonstrates that there were no such problems on her arrival).[20][21] Other users of the term include American politician Richard Blumenthal, who incorrectly stated on a number of occasions that he had served in Vietnam during the Vietnam War.[20]

See also[edit]

- Error (linguistics)

- Auditory processing disorder

- Barbarism (grammar)

- Epenthesis

- Errors in early word use

- Folk etymology

- FOXP2

- Developmental verbal dyspraxia

- Malapropism

- Metathesis (linguistics)

- Signorelli parapraxis

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Carroll, David (1986). Psychology of language. Pacific Grove, CA, USA: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co. pp. 253–256. ISBN 978-0-534-05640-7. OCLC 12583436.

- ^ a b Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Routledge: London 1996, 449.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tserdanelis, Georgios; Wai Sum Wong (2004). Language files: materials for an introduction to language & linguistics. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. pp. 320–324. ISBN 978-0-8142-0970-7. OCLC 54503589.

- ^ Dell, Gary S.; Reich, Peter A. (December 1981). «Stages in sentence production: An analysis of speech error data». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 20 (6): 611–629. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(81)90202-4.

- ^ «Slips of the Tongue». Psychology Today. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ a b Preston, Jonathan; Byun, Tara (November 2015). «Residual Speech Errors: Causes, Implications, Treatment». Seminars in Speech and Language. 36 (4): 215–216. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1562904. ISSN 0734-0478. PMID 26458196.

- ^ Fromkin, Victoria. «The Non-Anomalous Nature of Anomalous Utterances» (PDF). Stanford.

- ^ a b c d e f Hockett, Charles F. (1973). «Where the tongue slips, there slip I». In Victoria Fromkin (ed.). Speech errors as linguistic evidence. The Hague: Mouton. pp. 97–114. OCLC 1009093.

- ^ Pfau, Roland. Grammar as processor: a distributed morphology account of spontaneous speech. John Benjamins Publishing Co.: Amsterdam 2009, 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Eysenck, Michael W.; Keane, Mark A. (2005). Cognitive Psychology: A Student’s Handbook. Psychology Press (UK). p. 402. ISBN 978-1-84169-359-0. OCLC 608153953.

- ^ Anderson, John R. Kognitive Psychologie. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Heidelberg 1996 (2nd edition), 353.

- ^ a b Smith, Derek J. «Speech Errors, Speech Production Models, and Speech Pathology.» Human Information Processing. Date of last revision: 12 December 2003. Date of access: 27 February 2010. «Speech-errors». Archived from the original on 5 December 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2007..

- ^ a b Fromkin, Victoria (1973). «Introduction». In Victoria Fromkin (ed.). Speech errors as linguistic evidence. The Hague: Mouton. p. 13. ISBN 978-90-279-2668-5. OCLC 1009093.

- ^ a b Baars, Bernard J.; Michael T. Motley; Donald G. MacKay (August 1975). «Output editing for lexical status in artificially elicited slips of the tongue». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 14 (4): 382–391. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(75)80017-X.

- ^ Clark HH, Fox Tree JE (May 2002). «Using uh and um in spontaneous speaking». Cognition. 84 (1): 73–111. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.5.7958. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(02)00017-3. PMID 12062148. S2CID 37642332.

- ^ Schachter, Stanley; Nicholas Christenfeld; Bernard Ravina; Frances Bilous (March 1991). «Speech Disfluency and the Structure of Knowledge». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 60 (3): 362–367. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.362.[dead link]

- ^ Garrett, M. F. (1975). «The analysis of sentence production.». In Gordon H Bower (ed.). The Psychology of learning and motivation. Volume 9 : advances in research and theory. New York: Academic Press. pp. 133–177. ISBN 978-0-12-543309-9. OCLC 24672687.

- ^ Motley, Michael T.; Bernard J. Baars (1976). «Semantic bias effects on the outcomes of verbal slips». Cognition. 43 (2): 177–187. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(76)90003-2. S2CID 53152698.[dead link]

- ^ Hendrik Hertzberg (21 April 2008). «Mr. and Ms. Spoken». The New Yorker. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Dominic Lawson (23 May 2010). «Don’t lie – try misspeaking instead». The Sunday Times. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ «Does ‘misspeak’ mean lying?». BBC News. 26 March 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

Further reading[edit]

- Bock, J. K. (1982). Toward a cognitive psychology of syntax. Psychological Review, 89, 1-47.

- Garrett, M. F. (1976). Syntactic processing in sentence production. In E. Walker & R. Wales (Eds.), New approaches to language mechanisms (pp. 231–256). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Garrett, M. F. (1980). Levels of processing in sentence production. In B. Butterworth (Ed.), Language production: Vol. 1. Speech and talk (pp. 177–220). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Hickok G (2012). «The cortical organization of speech processing: feedback control and predictive coding the context of a dual-stream model». J Commun Disord. 45 (6): 393–402. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2012.06.004. PMC 3468690. PMID 22766458.

- Jescheniak, J.D., Levelt, W.J.M (1994). Word Frequency Effects in Speech Production: Retrieval of Syntactic Information and of Phonological Form. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, Vol. 20, (pp. 824–843)

- Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Poeppel D, Emmorey K, Hickok G, Pylkkänen L (October 2012). «Towards a new neurobiology of language». J. Neurosci. 32 (41): 14125–31. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3244-12.2012. PMC 3495005. PMID 23055482.

- Reichman, R. (1981). Plain Speaking: A Theory and Grammar of Spontaneous Discourse. Cambridge, MA

- Bache, Richard Meade. (1869). Vulgarisms and Other Errors of Speech.

External links[edit]

- «Fromkins Speech Error Database — Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics». www.mpi.nl. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

Речь – это канал развития интеллекта,

чем раньше будет усвоен язык,

тем легче и полнее будут усваиваться знания.

Николай Иванович Жинкин,

советский лингвист и психолог

Речь мыслится нами как абстрактная категория, недоступная для непосредственного восприятия. А между тем это – важнейший показатель культуры человека, его интеллекта и мышления, способ познания сложных связей природы, вещей, общества и передачи этой информации путём коммуникации.

Очевидно, что и обучаясь, и уже пользуясь чем-либо, мы в силу неумения или незнания совершаем ошибки. И речь, как и другие виды деятельности человека (в которых язык – важная составляющая часть), в данном отношении не является исключением. Ошибки делают все люди, как в письменной, так и в устной речи. Более того, понятие культуры речи, как представление о «речевом идеале», неразрывно связано с понятием речевой ошибки. По сути это – части одного процесса, а, значит, стремясь к совершенству, мы должны уметь распознавать речевые ошибки и искоренять их.

Что такое ошибки в языке? Зачем говорить грамотно?

Сто лет назад человек считался грамотным, если он умел писать и читать на родном языке. Сейчас грамотным называют того, кто не только читает и говорит, но и пишет в соответствии с правилами языка, которые нам дают филологи и система образования. В устаревшем смысле мы все грамотные. Но далеко не все из нас всегда правильно ставят знаки препинания или пишут трудные слова.

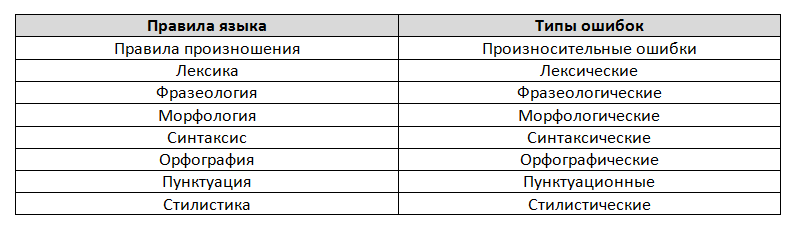

Виды речевых ошибок

Сначала разберёмся с тем, что такое речевые ошибки. Речевые ошибки – это любые случаи отклонения от действующих языковых норм. Без их знания человек может нормально жить, работать и настраивать коммуникацию с другими. Но вот эффективность совершаемых действий в определённых случаях может страдать. В связи с этим возникает риск быть недопонятым или понятым превратно. А в ситуациях, когда от этого зависит наш личный успех, подобное недопустимо.

Автором приведённой ниже классификации речевых ошибок является доктор филологических наук Ю. В. Фоменко. Его деление, по нашему мнению, наиболее простое, лишённое академической вычурности и, как следствие, понятное даже тем, кто не имеет специального образования.

Виды речевых ошибок:

Примеры и причины возникновения речевых ошибок

С. Н. Цейтлин пишет: «В качестве фактора, способствующего возникновению речевых ошибок, выступает сложность механизма порождения речи». Давайте рассмотрим частные случаи, опираясь на предложенную выше классификацию видов речевых ошибок.

Произносительные ошибки

Произносительные или орфоэпические ошибки возникают в результате нарушения правил орфоэпии. Другими словами, причина кроется в неправильном произношении звуков, звукосочетаний, отдельных грамматических конструкций и заимствованных слов. К ним также относятся акцентологические ошибки – нарушение норм ударения. Примеры:

Произношение: «конечно» (а не «конешно»), «пошти» («почти»), «плотит» («платит»), «прецендент» («прецедент»), «иликтрический» («электрический»), «колидор» («коридор»), «лаболатория» («лаборатория»), «тыща» («тысяча»), «щас» («сейчас»).

Неправильное ударение: «зво́нит», «диа́лог», «до́говор», «ката́лог», «путепро́вод», «а́лкоголь», «свекла́», «феноме́н», «шо́фер», «э́ксперт».

Лексические ошибки

Лексические ошибки – нарушение правил лексики, прежде всего – употребление слов в несвойственных им значениях, искажение морфемной формы слов и правил смыслового согласования. Они бывают нескольких видов.

Употребление слова в несвойственном ему значении. Это самая распространённая лексическая речевая ошибка. В рамках этого типа выделяют три подтипа:

- Смешение слов, близких по значению: «Он обратно прочитал книжку».

- Смешение слов, близких по звучанию: экскаватор – эскалатор, колос – колосс, индианка – индейка, одинарный – ординарный.

- Смешение слов, близких по значению и звучанию: абонент – абонемент, адресат – адресант, дипломат – дипломант, сытый – сытный, невежа – невежда. «Касса для командировочных» (нужно – командированных).

Словосочинительство. Примеры ошибок: грузинец, героичество, подпольцы, мотовщик.

Нарушение правил смыслового согласования слов. Смысловое согласование – это взаимное приспособление слов по линии их вещественных значений. Например, нельзя сказать: «Я поднимаю этот тост», поскольку «поднимать» значит «перемещать», что не согласовывается с пожеланием. «Через приоткрытую настежь дверь», – речевая ошибка, потому что дверь не может быть и приоткрыта (открыта немного), и настежь (широко распахнута) одновременно.

Сюда же относятся плеоназмы и тавтологии. Плеоназм – словосочетание, в котором значение одного компонента целиком входит в значение другого. Примеры: «май месяц», «маршрут движения», «адрес местожительства», «огромный мегаполис», «успеть вовремя». Тавтология – словосочетание, члены которого имеют один корень: «Задали задание», «Организатором выступила одна общественная организация», «Желаю долгого творческого долголетия».

Фразеологические ошибки

Фразеологические ошибки возникают, когда искажается форма фразеологизмов или они употребляются в несвойственном им значении. Ю. В. Фоменко выделяет 7 разновидностей:

- Изменение лексического состава фразеологизма: «Пока суть да дело» вместо «Пока суд да дело»;

- Усечение фразеологизма: «Ему было впору биться об стенку» (фразеологизм: «биться головой об стенку»);

- Расширение лексического состава фразеологизма: «Вы обратились не по правильному адресу» (фразеологизм: обратиться по адресу);

- Искажение грамматической формы фразеологизма: «Терпеть не могу сидеть сложив руки». Правильно: «сложа»;

- Контаминация (объединение) фразеологизмов: «Нельзя же все делать сложа рукава» (объединение фразеологизмов «спустя рукава» и «сложа руки»);

- Сочетание плеоназма и фразеологизма: «Случайная шальная пуля»;

- Употребление фразеологизма в несвойственном значении: «Сегодня мы будем говорить о фильме от корки до корки».

Морфологические ошибки

Морфологические ошибки – неправильное образование форм слова. Примеры таких речевых ошибок: «плацкарт», «туфель», «полотенцев», «дешевше», «в полуторастах километрах».

Синтаксические ошибки

Синтаксические ошибки связаны с нарушением правил синтаксиса – конструирования предложений, правил сочетания слов. Их разновидностей очень много, поэтому приведём лишь некоторые примеры.

- Неправильное согласование: «В шкафу стоят много книг»;

- Неправильное управление: «Оплачивайте за проезд»;

- Синтаксическая двузначность: «Чтение Маяковского произвело сильное впечатление» (читал Маяковский или читали произведения Маяковского?);

- Смещение конструкции: «Первое, о чём я вас прошу, – это о внимании». Правильно: «Первое, о чём я вас прошу, – это внимание»;

- Лишнее соотносительное слово в главном предложении: «Мы смотрели на те звёзды, которые усеяли всё небо».

Орфографические ошибки

Этот вид ошибок возникает из-за незнания правил написания, переноса, сокращения слов. Характерен для письменной речи. Например: «сабака лаяла», «сидеть на стули», «приехать на вогзал», «русск. язык», «грамм. ошибка».

Пунктуационные ошибки

Пунктуационные ошибки – неправильное употребление знаков препинания при письме.

Стилистические ошибки

Этой теме мы посвятили отдельный материал.

Пути исправления и предупреждения речевых ошибок

Как предупредить речевые ошибки? Работа над своей речью должна включать:

- Чтение художественной литературы.

- Посещение театров, музеев, выставок.

- Общение с образованными людьми.

- Постоянная работа над совершенствованием культуры речи.

Онлайн-курс «Русский язык»

Речевые ошибки – одна из самых проблемных тем, которой уделяется мало внимания в школе. Тем русского языка, в которых люди чаще всего допускают ошибки, не так уж много — примерно 20. Именно данным темам мы решили посвятить курс «Русский язык». На занятиях вы получите возможность отработать навык грамотного письма по специальной системе многократных распределенных повторений материала через простые упражнения и специальные техники запоминания.

Подробнее Купить сейчас

Источники

- Беззубов А. Н. Введение в литературное редактирование. – Санкт-Петербург, 1997.

- Савко И. Э. Основные речевые и грамматические ошибки

- Сергеева Н. М. Ошибки речевые, грамматические, этические, фактологические…

- Фоменко Ю. В. Типы речевых ошибок. – Новосибирск: НГПУ, 1994.

- Цейтлин С. Н. Речевые ошибки и их предупреждение. – М.: Просвещение, 1982.

Отзывы и комментарии

А теперь вы можете потренироваться и найти речевые ошибки в данной статье или поделиться другими известными вам примерами. Кроме того, обратите внимание на наш курс по развитию грамотности.