From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

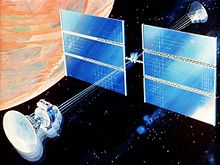

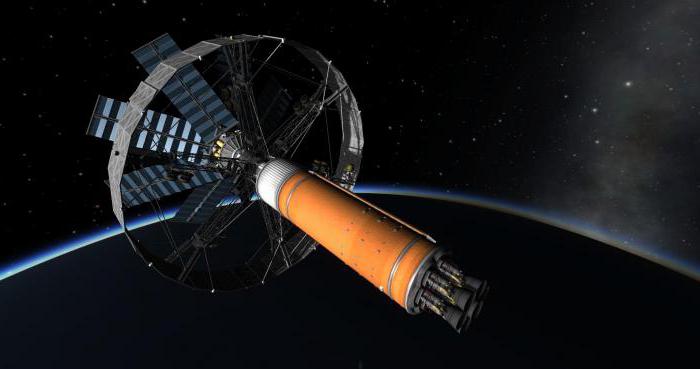

Proposed Nautilus-X International space station centrifuge demo concept, 2011.

Artificial gravity is the creation of an inertial force that mimics the effects of a gravitational force, usually by rotation.[1]

Artificial gravity, or rotational gravity, is thus the appearance of a centrifugal force in a rotating frame of reference (the transmission of centripetal acceleration via normal force in the non-rotating frame of reference), as opposed to the force experienced in linear acceleration, which by the equivalence principle is indistinguishable from gravity.

In a more general sense, «artificial gravity» may also refer to the effect of linear acceleration, e.g. by means of a rocket engine.[1]

Rotational simulated gravity has been used in simulations to help astronauts train for extreme conditions.[2]

Rotational simulated gravity has been proposed as a solution in human spaceflight to the adverse health effects caused by prolonged weightlessness.

However, there are no current practical outer space applications of artificial gravity for humans due to concerns about the size and cost of a spacecraft necessary to produce a useful centripetal force comparable to the gravitational field strength on Earth (g).[3]

Scientists are concerned about the effect of such a system on the inner ear of the occupants. The concern is that using centripetal force to create artificial gravity will cause disturbances in the inner ear leading to nausea and disorientation. The adverse effects may prove intolerable for the occupants.[4]

Centripetal force[edit]

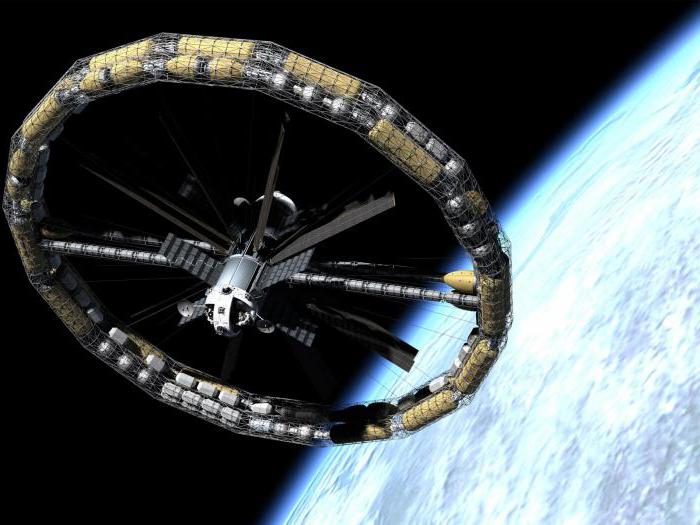

Artificial gravity space station. 1969 NASA concept. A drawback is that the astronauts would be moving between higher gravity near the ends and lower gravity near the center.

In the context of a rotating space station, it is the radial force provided by the spacecraft’s hull that acts as centripetal force. Thus, the «gravity» force felt by an object is the centrifugal force perceived in the rotating frame of reference as pointing «downwards» towards the hull.

By Newton’s Third Law the value of little g (the perceived «downward» acceleration) is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the centripetal acceleration.

Differences from normal gravity[edit]

Balls in a rotating spacecraft

From the perspective of people rotating with the habitat, artificial gravity by rotation behaves similarly to normal gravity but with the following differences, which can be mitigated by increasing the radius of a space station.

- Centrifugal force varies with distance: Unlike real gravity, the apparent centrifugal force felt by observers in the habitat pushes radially outward from the axis, and the centrifugal force is directly proportional to the distance from the axis of the habitat. With a small radius of rotation, a standing person’s head would feel significantly less gravity than their feet.[5] Likewise, passengers who move in a space station experience changes in apparent weight in different parts of the body.[6]

- The Coriolis effect gives an apparent force that acts on objects that are moving relative to a rotating reference frame. This apparent force acts at right angles to the motion and the rotation axis and tends to curve the motion in the opposite sense to the habitat’s spin. If an astronaut inside a rotating artificial gravity environment moves towards or away from the axis of rotation, they will feel a force pushing them in or against the direction of spin. These forces act on the semicircular canals of the inner ear and can cause dizziness.[7] Lengthening the period of rotation (lower spin rate) reduces the Coriolis force and its effects. It is generally believed that at 2 rpm or less, no adverse effects from the Coriolis forces will occur, although humans have been shown to adapt to rates as high as 23 rpm.[8]

- Changes in the rotation axis or rate of a spin would cause a disturbance in the artificial gravity field and stimulate the semicircular canals (refer to above). Thus, the rotation of a space station would need to be adequately stabilized, and any operations to deliberately change the rotation would need to be done slowly enough to be imperceptible.[7]

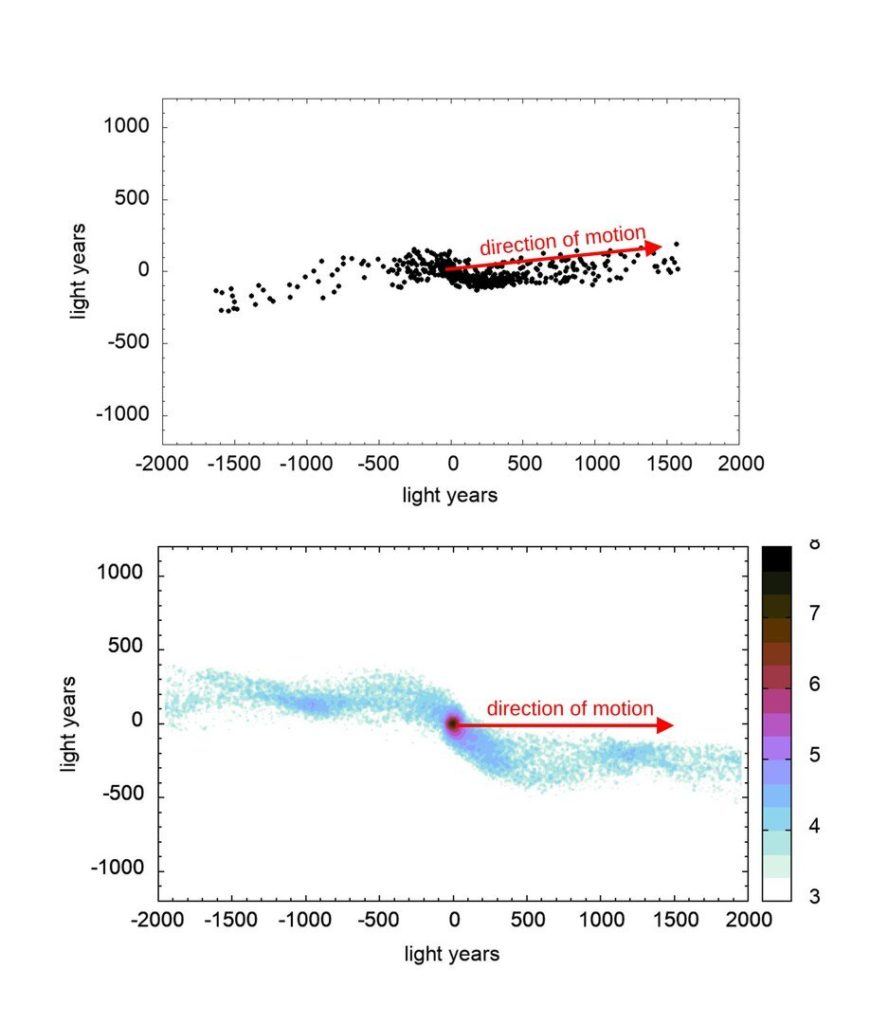

Speed in rpm for a centrifuge of a given radius to achieve a given g-force

Human spaceflight[edit]

The Gemini 11 mission attempted to produce artificial gravity by rotating the capsule around the Agena Target Vehicle to which it was attached by a 36-meter tether. They were able to generate a small amount of artificial gravity, about 0.00015 g, by firing their side thrusters to slowly rotate the combined craft like a slow-motion pair of bolas.[9] The resultant force was too small to be felt by either astronaut, but objects were observed moving towards the «floor» of the capsule.[10]

Health benefits[edit]

Artificial gravity has been suggested for interplanetary journeys to Mars

Artificial gravity has been suggested as a solution to various health risks associated with spaceflight.[11] In 1964, the Soviet space program believed that a human could not survive more than 14 days in space for fear that the heart and blood vessels would be unable to adapt to the weightless conditions.[12] This fear was eventually discovered to be unfounded as spaceflights have now lasted up to 437 consecutive days,[13] with missions aboard the International Space Station commonly lasting 6 months. However, the question of human safety in space did launch an investigation into the physical effects of prolonged exposure to weightlessness. In June 1991, a Spacelab Life Sciences 1 flight performed 18 experiments on two men and two women over nine days. In an environment without gravity, it was concluded that the response of white blood cells and muscle mass decreased. Additionally, within the first 24 hours spent in a weightless environment, blood volume decreased by 10%.[14][3][1] Long weightless periods can cause brain swelling and eyesight problems.[15] Upon return to earth, the effects of prolonged weightlessness continue to affect the human body as fluids pool back to the lower body, the heart rate rises, a drop in blood pressure occurs and there is a reduced tolerance for exercise.[14]

Artificial gravity, for its ability to mimic the behavior of gravity on the human body, has been suggested as one of the most encompassing manners of combating the physical effects inherent in weightless environments. Other measures that have been suggested as symptomatic treatments include exercise, diet, and Pingvin suits. However, criticism of those methods lies in the fact that they do not fully eliminate health problems and require a variety of solutions to address all issues. Artificial gravity, in contrast, would remove the weightlessness inherent in space travel. By implementing artificial gravity, space travelers would never have to experience weightlessness or the associated side effects.[1] Especially in a modern-day six-month journey to Mars, exposure to artificial gravity is suggested in either a continuous or intermittent form to prevent extreme debilitation to the astronauts during travel.[11]

Proposals[edit]

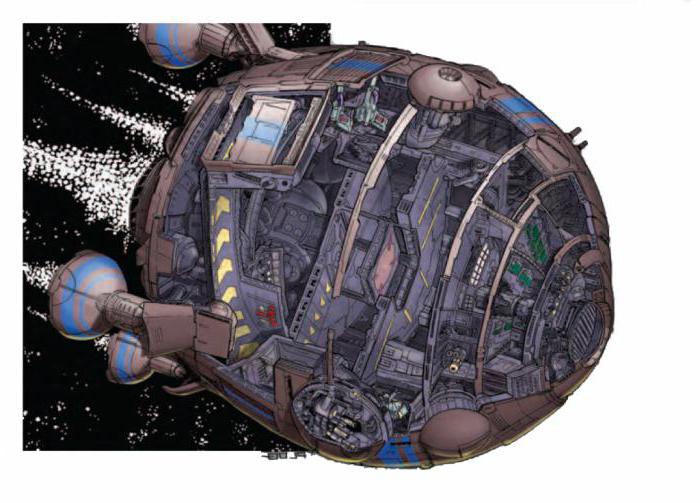

Rotating Mars spacecraft – 1989 NASA concept.

Several proposals have incorporated artificial gravity into their design:

- Discovery II: a 2005 vehicle proposal capable of delivering a 172-metric-ton crew to Jupiter’s orbit in 118 days. A very small portion of the 1,690-metric-ton craft would incorporate a centrifugal crew station.[16]

- Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle (MMSEV): a 2011 NASA proposal for a long-duration crewed space transport vehicle; it included a rotational artificial gravity space habitat intended to promote crew health for a crew of up to six persons on missions of up to two years in duration. The torus-ring centrifuge would utilize both standard metal-frame and inflatable spacecraft structures and would provide 0.11 to 0.69 g if built with the 40 feet (12 m) diameter option.[17][18]

- ISS Centrifuge Demo: a 2011 NASA proposal for a demonstration project preparatory to the final design of the larger torus centrifuge space habitat for the Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle. The structure would have an outside diameter of 30 feet (9.1 m) with a ring interior cross-section diameter of 30 inches (760 mm). It would provide 0.08 to 0.51 g partial gravity. This test and evaluation centrifuge would have the capability to become a Sleep Module for the ISS crew.[17]

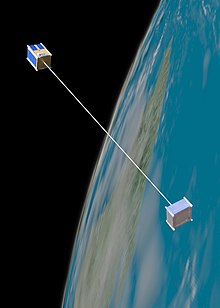

Artist view of TEMPO³ in orbit.

- Mars Direct: A plan for a crewed Mars mission created by NASA engineers Robert Zubrin and David Baker in 1990, later expanded upon in Zubrin’s 1996 book The Case for Mars. The «Mars Habitat Unit», which would carry astronauts to Mars to join the previously launched «Earth Return Vehicle», would have had artificial gravity generated during flight by tying the spent upper stage of the booster to the Habitat Unit, and setting them both rotating about a common axis.[19]

- The proposed Tempo3 mission rotates two halves of a spacecraft connected by a tether to test the feasibility of simulating gravity on a crewed mission to Mars.[20]

- The Mars Gravity Biosatellite was a proposed mission meant to study the effect of artificial gravity on mammals. An artificial gravity field of 0.38 g (equivalent to Mars’s surface gravity) was to be produced by rotation (32 rpm, radius of ca. 30 cm). Fifteen mice would have orbited Earth (Low Earth orbit) for five weeks and then land alive.[21] However, the program was canceled on 24 June 2009, due to a lack of funding and shifting priorities at NASA.[22]

Issues with implementation[edit]

Some of the reasons that artificial gravity remains unused today in spaceflight trace back to the problems inherent in implementation. One of the realistic methods of creating artificial gravity is the centrifugal effect caused by the centripetal force of the floor of a rotating structure pushing up on the person. In that model, however, issues arise in the size of the spacecraft. As expressed by John Page and Matthew Francis, the smaller a spacecraft (the shorter the radius of rotation), the more rapid the rotation that is required. As such, to simulate gravity, it would be better to utilize a larger spacecraft that rotates slowly. The requirements on size about rotation are due to the differing forces on parts of the body at different distances from the axis of rotation. If parts of the body closer to the rotational axis experience a force that is significantly different from parts farther from the axis, then this could have adverse effects. Additionally, questions remain as to what the best way is to initially set the rotating motion in place without disturbing the stability of the whole spacecraft’s orbit. At the moment, there is not a ship massive enough to meet the rotation requirements, and the costs associated with building, maintaining, and launching such a craft are extensive.[3]

In general, with the limited health effects present in shorter spaceflights, as well as the high cost of research, the application of artificial gravity is often stunted and sporadic.[1][14]

In science fiction[edit]

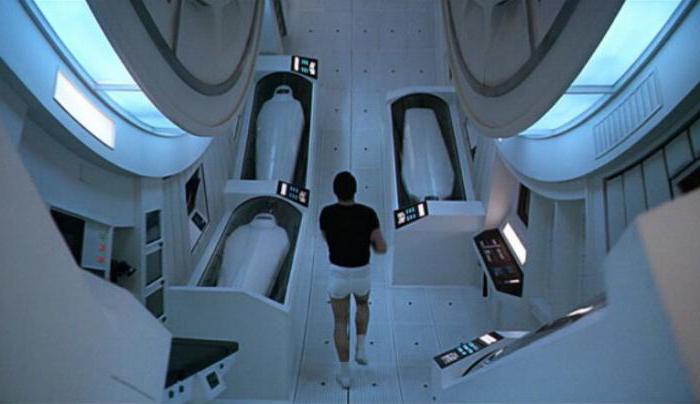

Several science fiction novels, films, and series have featured artificial gravity production. In the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, a rotating centrifuge in the Discovery spacecraft provides artificial gravity.

In the novel The Martian, the Hermes spacecraft achieves artificial gravity by design; it employs a ringed structure, at whose periphery forces around 40% of Earth’s gravity are experienced, similar to Mars’ gravity. The movie Interstellar features a spacecraft called the Endurance that can rotate on its central axis to create artificial gravity, controlled by retro thrusters on the ship. The 2021 film Stowaway features the upper stage of a launch vehicle connected by 450-meter long tethers to the ship’s main hull, acting as a counterweight for inertia-based artificial gravity.[23]

Linear acceleration[edit]

Linear acceleration is another method of generating artificial gravity, by using the thrust from a spacecraft’s engines to create the illusion of being under a gravitational pull. A spacecraft under constant acceleration in a straight line would have the appearance of a gravitational pull in the direction opposite to that of the acceleration, as the thrust from the engines would cause the spacecraft to «push» itself up into the objects and persons inside of the vessel, thus creating the feeling of weight. This is because of Newton’s third law: the weight that one would feel standing in a linearly accelerating spacecraft would not be a true gravitational pull, but simply the reaction of oneself pushing against the craft’s hull as it pushes back. Similarly, objects that would otherwise be free-floating within the spacecraft if it were not accelerating would «fall» towards the engines when it started accelerating, as a consequence of Newton’s first law: the floating object would remain at rest, while the spacecraft would accelerate towards it, and appear to an observer within that the object was «falling».

To emulate artificial gravity on Earth, spacecraft using linear acceleration gravity may be built similar to a skyscraper, with its engines as the bottom «floor». If the spacecraft were to accelerate at the rate of 1 g—Earth’s gravitational pull—the individuals inside would be pressed into the hull at the same force, and thus be able to walk and behave as if they were on Earth.

This form of artificial gravity is desirable because it could functionally create the illusion of a gravity field that is uniform and unidirectional throughout a spacecraft, without the need for large, spinning rings, whose fields may not be uniform, not unidirectional with respect to the spacecraft, and require constant rotation. This would also have the advantage of relatively high speed: a spaceship accelerating at 1 g, 9.8 m/s2, for the first half of the journey, and then decelerating for the other half, could reach Mars within a few days.[24] Similarly, a hypothetical space travel using constant acceleration of 1 g for one year would reach relativistic speeds and allow for a round trip to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri. As such, low-impulse but long-term linear acceleration has been proposed for various interplanetary missions. For example, even heavy (100 ton) cargo payloads to Mars could be transported to Mars in 27 months and retain approximately 55 percent of the LEO vehicle mass upon arrival into a Mars orbit, providing a low-gravity gradient to the spacecraft during the entire journey.[25]

This form of gravity is not without challenges, however. At present, the only practical engines that could propel a vessel fast enough to reach speeds comparable to Earth’s gravitational pull require chemical reaction rockets, which expel reaction mass to achieve thrust, and thus the acceleration could only last for as long as a vessel had fuel. The vessel would also need to be constantly accelerating and at a constant speed to maintain the gravitational effect, and thus would not have gravity while stationary, and could experience significant swings in g-forces if the vessel were to accelerate above or below 1 g. Further, for point-to-point journeys, such as Earth-Mars transits, vessels would need to constantly accelerate for half the journey, turn off their engines, perform a 180° flip, reactivate their engines, and then begin decelerating towards the target destination, requiring everything inside the vessel to experience weightlessness and possibly be secured down for the duration of the flip.

A propulsion system with a very high specific impulse (that is, good efficiency in the use of reaction mass that must be carried along and used for propulsion on the journey) could accelerate more slowly producing useful levels of artificial gravity for long periods of time. A variety of electric propulsion systems provide examples. Two examples of this long-duration, low-thrust, high-impulse propulsion that have either been practically used on spacecraft or are planned in for near-term in-space use are Hall effect thrusters and Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rockets (VASIMR). Both provide very high specific impulse but relatively low thrust, compared to the more typical chemical reaction rockets. They are thus ideally suited for long-duration firings which would provide limited amounts of, but long-term, milli-g levels of artificial gravity in spacecraft.[citation needed]

In a number of science fiction plots, acceleration is used to produce artificial gravity for interstellar spacecraft, propelled by as yet theoretical or hypothetical means.

This effect of linear acceleration is well understood, and is routinely used for 0 g cryogenic fluid management for post-launch (subsequent) in-space firings of upper stage rockets.[26]

Roller coasters, especially launched roller coasters or those that rely on electromagnetic propulsion, can provide linear acceleration «gravity», and so can relatively high acceleration vehicles, such as sports cars. Linear acceleration can be used to provide air-time on roller coasters and other thrill rides.

Simulating lunar gravity[edit]

In January 2022 China was reported by the South China Morning Post to have built a small (60 centimetres (24 in) diameter) research facility to simulate low lunar gravity with the help of magnets.[27][28] The facility was reportedly partly inspired by the work of Andre Geim (who later shared the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics for his research on graphene) and Michael Berry, who both shared the Ig Nobel Prize in Physics in 2000 for the magnetic levitation of a frog.[27][28]

Simulating microgravity[edit]

Parabolic flight[edit]

Weightless Wonder is the nickname for the NASA aircraft that flies parabolic trajectories. Briefly, it provides a nearly weightless environment to train astronauts, conduct research, and film motion pictures. The parabolic trajectory creates a vertical linear acceleration that matches that of gravity, giving zero-g for a short time, usually 20–30 seconds, followed by approximately 1.8g for a similar period. The nickname Vomit Comet is also used to refer to motion sickness that aircraft passengers often experience during these parabolic trajectories. Such reduced gravity aircraft are nowadays operated by several organizations worldwide.[citation needed]

Neutral buoyancy[edit]

The Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) is an astronaut training facility at the Sonny Carter Training Facility at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.[29] The NBL is a large indoor pool of water, the largest in the world,[30] in which astronauts may perform simulated EVA tasks in preparation for space missions. The NBL contains full-sized mock-ups of the Space Shuttle cargo bay, flight payloads, and the International Space Station (ISS).[31]

The principle of neutral buoyancy is used to simulate the weightless environment of space.[29] The suited astronauts are lowered into the pool using an overhead crane and their weight is adjusted by support divers so that they experience no buoyant force and no rotational moment about their center of mass.[29] The suits worn in the NBL are down-rated from fully flight-rated EMU suits like those in use on the space shuttle and International Space Station.

The NBL tank is 202 feet (62 m) in length, 102 feet (31 m) wide, and 40 feet 6 inches (12.34 m) deep, and contains 6.2 million gallons (23.5 million liters) of water.[31][32] Divers breathe nitrox while working in the tank.[33][34]

Neutral buoyancy in a pool is not weightlessness, since the balance organs in the inner ear still sense the up-down direction of gravity. Also, there is a significant amount of drag presented by water.[35] Generally, drag effects are minimized by doing tasks slowly in the water. Another difference between neutral buoyancy simulation in a pool and actual EVA during spaceflight is that the temperature of the pool and the lighting conditions are maintained constant.

Speculative or fictional mechanisms[edit]

In science fiction, artificial gravity (or cancellation of gravity) or «paragravity»[36][37] is sometimes present in spacecraft that are neither rotating nor accelerating. At present, there is no confirmed technique as such that can simulate gravity other than actual mass or acceleration. There have been many claims over the years of such a device. Eugene Podkletnov, a Russian engineer, has claimed since the early 1990s to have made such a device consisting of a spinning superconductor producing a powerful «gravitomagnetic field», but there has been no verification or even negative results from third parties. In 2006, a research group funded by ESA claimed to have created a similar device that demonstrated positive results for the production of gravitomagnetism, although it produced only 0.0001 g.[38] This result has not been replicated.

See also[edit]

- Non-inertial reference frame – Reference frame that undergoes acceleration with respect to an inertial frame

- Anti-gravity – Idea of creating a place or object that is free from the force of gravity

- Gravitational shielding – Hypothetical shielding of an object from gravity

- Coriolis effect – Force on objects moving within a reference frame that rotates with respect to an inertial frame

- Centrifuge Accommodations Module – Cancelled element of the International Space Station

- Fictitious force – Force on objects moving within a reference frame that rotates with respect to an inertial frame.

- Rotating wheel space station

- Space habitat – Type of space station, intended as a permanent settlement

- Space travel under constant acceleration – Proposed mode of space travel

- Stanford torus – Proposed NASA design for space habitat

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Young, Laurence; Yajima, Kazuyoshi; Paloski, William, eds. (September 2009). ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY RESEARCH TO ENABLE HUMAN SPACE EXPLORATION (PDF). International Academy of Astronautics. ISBN 978-2-917761-04-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Strauss, Samuel (July 2008). «Space medicine at the NASA-JSC, neutral buoyancy laboratory». Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 79 (7): 732–733. ISSN 0095-6562. LCCN 75641492. OCLC 165744230. PMID 18619137.

- ^ a b c Feltman, Rachel (3 May 2013). «Why Don’t We Have Artificial Gravity?». Popular Mechanics. ISSN 0032-4558. OCLC 671272936. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Clément, Gilles R.; Bukley, Angelia P.; Paloski, William H. (June 17, 2015). «Artificial gravity as a countermeasure for mitigating physiological deconditioning during long-duration space missions». Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 9: 92. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2015.00092. ISSN 1662-5137. PMC 4470275. PMID 26136665.

- ^ Fifth Symposium on the Role of the Vestibular Organs in Space Exploration: Held Under the Auspices of the Committee on Hearing, Bioacoustics, and Biomechanics, National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, and Assisted by the Office of Advanced Research and Technology, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1973. p. 25.

- ^ Davis, Bl; Cavanagh, Pr; Perry, Je (September 1994). «Locomotion in a rotating space station: a synthesis of new data with established concepts». Gait & Posture. 2 (3): 157–165. doi:10.1016/0966-6362(94)90003-5. PMID 11539277.

- ^ a b Larson, Carl Alfred (1969). Rotating Space Station Stabilization Criteria for Artificial Gravity. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ Hecht, H.; Brown, E. L.; Young, L. R.; et al. (June 2–7, 2002). «Adapting to artificial gravity (AG) at high rotational speeds». Life in Space for Life on Earth. Proceedings of «Life in space for life on Earth». 8th European Symposium on Life Sciences Research in Space. 23rd Annual International Gravitational Physiology Meeting. 23 (1): P1-5. Bibcode:2002ESASP.501..151H. PMID 14703662.

- ^ Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Manned Spacecraft, Second Revision. New York, NY, USA: MacMillan. pp. 180–182. ISBN 978-0-02-542820-1.

- ^ Clément G, Bukley A (2007) Artificial Gravity. Springer: New York

- ^ a b «Artificial Gravity as a Countermeasure for Mitigating Physiological Deconditioning During Long-Duration Space Missions». June 17, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ «Weightlessness Obstacle to Space Survival». The Science News-Letter. 86 (7): 103. April 4, 1964. JSTOR 3947769.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (April 24, 2017). «Astronaut Peggy Whitson Sets NASA Record For Most Days In Space». NPR. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c David, Leonard (April 4, 1992). «Artificial Gravity and Space Travel». BioScience. 42 (3): 155–159. doi:10.2307/1311819. JSTOR 1311819.

- ^ «Prolonged space travel causes brain and eye abnormalities in astronauts».

- ^ Craig H. Williams; Leonard A. Dudzinski; Stanley K. Borowski; Albert J. Juhasz (March 2005). «Realizing «2001: A Space Odyssey»: Piloted Spherical Torus Nuclear Fusion Propulsion» (PDF). Cleveland, Ohio: NASA. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ a b NAUTILUS – X: Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle Archived March 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Mark L. Holderman, Future in Space Operations (FISO) Colloquium, 2011-01-26. Retrieved 2011-01-31

- ^

NASA NAUTILUS-X: multi-mission exploration vehicle includes a centrifuge, which would be tested at ISS Archived February 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, RLV and Space Transport News, 2011-01-28. Retrieved 2011-01-31 - ^ «NSS Review: The Case for Mars». www.nss.org. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ http://members.marssociety.org/TMQ/TMQ-V1-I1.pdf pg15-Tom Hill

- ^ Korzun, Ashley M.; Wagner, Erika B.; et al. (2007). Mars Gravity Biosatellite: Engineering, Science, and Education. 58th International Astronautical Congress.

- ^ «The Mars Gravity Biosatellite Program Is Closing Down». www.spaceref.com. June 24, 2009. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Kiang, Jessica (April 22, 2021). «Review: Anna Kendrick is lost, and found, in space in smart sci-fi ‘Stowaway’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Clément, Gilles; Bukley, Angelia P. (2007). Artificial Gravity. Springer New York. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-387-70712-9. Extract of page 35

- ^ VASIMR VX-200 Performance and Near-term SEP Capability for Unmanned Mars Flight Archived March 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Tim Glover, Future in Space Operations (FISO) Colloquium, pp. 22, 25, 2011-01-19. Retrieved 2011-02-01

- ^ Jon Goff; et al. (2009). «Realistic Near-Term Propellant Depots» (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

Developing techniques for manipulating fluids in microgravity, which typically fall into the category known as settled propellant handling. Research for cryogenic upper stages dating back to the Saturn S-IVB and Centaur found that providing a slight acceleration (as little as 10−4 to 10−5 g of acceleration) to the tank can make the propellants assume a desired configuration, which allows many of the main cryogenic fluid handling tasks to be performed in a similar fashion to terrestrial operations. The simplest and most mature settling technique is to apply thrust to the spacecraft, forcing the liquid to settle against one end of the tank.

- ^ a b «China building «Artificial Moon» that simulates low gravity with magnets». Futurism.com. Recurrent Ventures. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

Interestingly, the facility was partly inspired by previous research conducted by Russian physicist Andrew Geim in which he floated a frog with a magnet. The experiment earned Geim the Ig Nobel Prize in Physics, a satirical award for unusual scientific research. It’s cool that a quirky experiment involving floating a frog could lead to something approaching an honest-to-God antigravity chamber.

- ^ a b Chen, Stephen (January 12, 2022). «China has built an artificial moon that simulates low-gravity conditions on Earth». South China Morning Post. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

It is said to be the first of its kind and could play a key role in the country’s future lunar missions. The magnetic field supported the landscape and was inspired by experiments to levitate a frog.

- ^ a b c Strauss, S. (July 2008). «Space medicine at the NASA-JSC, neutral buoyancy laboratory». Aviat Space Environ Med. 79 (7): 732–3. PMID 18619137.

- ^ «Behind the scenes training». NASA. May 30, 2003. Archived from the original on November 24, 2002. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Strauss, S.; Krog, R.L.; Feiveson, A.H. (May 2005). «Extravehicular mobility unit training and astronaut injuries». Aviat Space Environ Med. 76 (5): 469–74. PMID 15892545. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ «NBL Characteristics». About the NBL. NASA. June 23, 2005. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007.

- ^ Fitzpatrick DT, Conkin J (2003). «Improved pulmonary function in working divers breathing nitrox at shallow depths». Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine. 30 (Supplement): 763–7. PMID 12862332. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Fitzpatrick DT, Conkin J (July 2003). «Improved pulmonary function in working divers breathing nitrox at shallow depths». Aviat Space Environ Med. 74 (7): 763–7. PMID 12862332. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ Pendergast D, Mollendorf J, Zamparo P, Termin A, Bushnell D, Paschke D (2005). «The influence of drag on human locomotion in water». Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine. 32 (1): 45–57. PMID 15796314. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Collision Orbit, 1942 by Jack Williamson

- ^ Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space by Carl Sagan, Chapter 19

- ^ «Toward a new test of general relativity?». Esa.int. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

External links[edit]

- List of peer review papers on artificial gravity

- TEDx talk about artificial gravity

- Revolving artificial gravity calculator

- Overview of artificial gravity in Sci-Fi and Space Science

- NASA’s Java simulation of artificial gravity

- Variable Gravity Research Facility (xGRF), concept with tethered rotating satellites, perhaps a Bigelow expandable module and a spent upper stage as a counterweight

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Proposed Nautilus-X International space station centrifuge demo concept, 2011.

Artificial gravity is the creation of an inertial force that mimics the effects of a gravitational force, usually by rotation.[1]

Artificial gravity, or rotational gravity, is thus the appearance of a centrifugal force in a rotating frame of reference (the transmission of centripetal acceleration via normal force in the non-rotating frame of reference), as opposed to the force experienced in linear acceleration, which by the equivalence principle is indistinguishable from gravity.

In a more general sense, «artificial gravity» may also refer to the effect of linear acceleration, e.g. by means of a rocket engine.[1]

Rotational simulated gravity has been used in simulations to help astronauts train for extreme conditions.[2]

Rotational simulated gravity has been proposed as a solution in human spaceflight to the adverse health effects caused by prolonged weightlessness.

However, there are no current practical outer space applications of artificial gravity for humans due to concerns about the size and cost of a spacecraft necessary to produce a useful centripetal force comparable to the gravitational field strength on Earth (g).[3]

Scientists are concerned about the effect of such a system on the inner ear of the occupants. The concern is that using centripetal force to create artificial gravity will cause disturbances in the inner ear leading to nausea and disorientation. The adverse effects may prove intolerable for the occupants.[4]

Centripetal force[edit]

Artificial gravity space station. 1969 NASA concept. A drawback is that the astronauts would be moving between higher gravity near the ends and lower gravity near the center.

In the context of a rotating space station, it is the radial force provided by the spacecraft’s hull that acts as centripetal force. Thus, the «gravity» force felt by an object is the centrifugal force perceived in the rotating frame of reference as pointing «downwards» towards the hull.

By Newton’s Third Law the value of little g (the perceived «downward» acceleration) is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the centripetal acceleration.

Differences from normal gravity[edit]

Balls in a rotating spacecraft

From the perspective of people rotating with the habitat, artificial gravity by rotation behaves similarly to normal gravity but with the following differences, which can be mitigated by increasing the radius of a space station.

- Centrifugal force varies with distance: Unlike real gravity, the apparent centrifugal force felt by observers in the habitat pushes radially outward from the axis, and the centrifugal force is directly proportional to the distance from the axis of the habitat. With a small radius of rotation, a standing person’s head would feel significantly less gravity than their feet.[5] Likewise, passengers who move in a space station experience changes in apparent weight in different parts of the body.[6]

- The Coriolis effect gives an apparent force that acts on objects that are moving relative to a rotating reference frame. This apparent force acts at right angles to the motion and the rotation axis and tends to curve the motion in the opposite sense to the habitat’s spin. If an astronaut inside a rotating artificial gravity environment moves towards or away from the axis of rotation, they will feel a force pushing them in or against the direction of spin. These forces act on the semicircular canals of the inner ear and can cause dizziness.[7] Lengthening the period of rotation (lower spin rate) reduces the Coriolis force and its effects. It is generally believed that at 2 rpm or less, no adverse effects from the Coriolis forces will occur, although humans have been shown to adapt to rates as high as 23 rpm.[8]

- Changes in the rotation axis or rate of a spin would cause a disturbance in the artificial gravity field and stimulate the semicircular canals (refer to above). Thus, the rotation of a space station would need to be adequately stabilized, and any operations to deliberately change the rotation would need to be done slowly enough to be imperceptible.[7]

Speed in rpm for a centrifuge of a given radius to achieve a given g-force

Human spaceflight[edit]

The Gemini 11 mission attempted to produce artificial gravity by rotating the capsule around the Agena Target Vehicle to which it was attached by a 36-meter tether. They were able to generate a small amount of artificial gravity, about 0.00015 g, by firing their side thrusters to slowly rotate the combined craft like a slow-motion pair of bolas.[9] The resultant force was too small to be felt by either astronaut, but objects were observed moving towards the «floor» of the capsule.[10]

Health benefits[edit]

Artificial gravity has been suggested for interplanetary journeys to Mars

Artificial gravity has been suggested as a solution to various health risks associated with spaceflight.[11] In 1964, the Soviet space program believed that a human could not survive more than 14 days in space for fear that the heart and blood vessels would be unable to adapt to the weightless conditions.[12] This fear was eventually discovered to be unfounded as spaceflights have now lasted up to 437 consecutive days,[13] with missions aboard the International Space Station commonly lasting 6 months. However, the question of human safety in space did launch an investigation into the physical effects of prolonged exposure to weightlessness. In June 1991, a Spacelab Life Sciences 1 flight performed 18 experiments on two men and two women over nine days. In an environment without gravity, it was concluded that the response of white blood cells and muscle mass decreased. Additionally, within the first 24 hours spent in a weightless environment, blood volume decreased by 10%.[14][3][1] Long weightless periods can cause brain swelling and eyesight problems.[15] Upon return to earth, the effects of prolonged weightlessness continue to affect the human body as fluids pool back to the lower body, the heart rate rises, a drop in blood pressure occurs and there is a reduced tolerance for exercise.[14]

Artificial gravity, for its ability to mimic the behavior of gravity on the human body, has been suggested as one of the most encompassing manners of combating the physical effects inherent in weightless environments. Other measures that have been suggested as symptomatic treatments include exercise, diet, and Pingvin suits. However, criticism of those methods lies in the fact that they do not fully eliminate health problems and require a variety of solutions to address all issues. Artificial gravity, in contrast, would remove the weightlessness inherent in space travel. By implementing artificial gravity, space travelers would never have to experience weightlessness or the associated side effects.[1] Especially in a modern-day six-month journey to Mars, exposure to artificial gravity is suggested in either a continuous or intermittent form to prevent extreme debilitation to the astronauts during travel.[11]

Proposals[edit]

Rotating Mars spacecraft – 1989 NASA concept.

Several proposals have incorporated artificial gravity into their design:

- Discovery II: a 2005 vehicle proposal capable of delivering a 172-metric-ton crew to Jupiter’s orbit in 118 days. A very small portion of the 1,690-metric-ton craft would incorporate a centrifugal crew station.[16]

- Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle (MMSEV): a 2011 NASA proposal for a long-duration crewed space transport vehicle; it included a rotational artificial gravity space habitat intended to promote crew health for a crew of up to six persons on missions of up to two years in duration. The torus-ring centrifuge would utilize both standard metal-frame and inflatable spacecraft structures and would provide 0.11 to 0.69 g if built with the 40 feet (12 m) diameter option.[17][18]

- ISS Centrifuge Demo: a 2011 NASA proposal for a demonstration project preparatory to the final design of the larger torus centrifuge space habitat for the Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle. The structure would have an outside diameter of 30 feet (9.1 m) with a ring interior cross-section diameter of 30 inches (760 mm). It would provide 0.08 to 0.51 g partial gravity. This test and evaluation centrifuge would have the capability to become a Sleep Module for the ISS crew.[17]

Artist view of TEMPO³ in orbit.

- Mars Direct: A plan for a crewed Mars mission created by NASA engineers Robert Zubrin and David Baker in 1990, later expanded upon in Zubrin’s 1996 book The Case for Mars. The «Mars Habitat Unit», which would carry astronauts to Mars to join the previously launched «Earth Return Vehicle», would have had artificial gravity generated during flight by tying the spent upper stage of the booster to the Habitat Unit, and setting them both rotating about a common axis.[19]

- The proposed Tempo3 mission rotates two halves of a spacecraft connected by a tether to test the feasibility of simulating gravity on a crewed mission to Mars.[20]

- The Mars Gravity Biosatellite was a proposed mission meant to study the effect of artificial gravity on mammals. An artificial gravity field of 0.38 g (equivalent to Mars’s surface gravity) was to be produced by rotation (32 rpm, radius of ca. 30 cm). Fifteen mice would have orbited Earth (Low Earth orbit) for five weeks and then land alive.[21] However, the program was canceled on 24 June 2009, due to a lack of funding and shifting priorities at NASA.[22]

Issues with implementation[edit]

Some of the reasons that artificial gravity remains unused today in spaceflight trace back to the problems inherent in implementation. One of the realistic methods of creating artificial gravity is the centrifugal effect caused by the centripetal force of the floor of a rotating structure pushing up on the person. In that model, however, issues arise in the size of the spacecraft. As expressed by John Page and Matthew Francis, the smaller a spacecraft (the shorter the radius of rotation), the more rapid the rotation that is required. As such, to simulate gravity, it would be better to utilize a larger spacecraft that rotates slowly. The requirements on size about rotation are due to the differing forces on parts of the body at different distances from the axis of rotation. If parts of the body closer to the rotational axis experience a force that is significantly different from parts farther from the axis, then this could have adverse effects. Additionally, questions remain as to what the best way is to initially set the rotating motion in place without disturbing the stability of the whole spacecraft’s orbit. At the moment, there is not a ship massive enough to meet the rotation requirements, and the costs associated with building, maintaining, and launching such a craft are extensive.[3]

In general, with the limited health effects present in shorter spaceflights, as well as the high cost of research, the application of artificial gravity is often stunted and sporadic.[1][14]

In science fiction[edit]

Several science fiction novels, films, and series have featured artificial gravity production. In the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, a rotating centrifuge in the Discovery spacecraft provides artificial gravity.

In the novel The Martian, the Hermes spacecraft achieves artificial gravity by design; it employs a ringed structure, at whose periphery forces around 40% of Earth’s gravity are experienced, similar to Mars’ gravity. The movie Interstellar features a spacecraft called the Endurance that can rotate on its central axis to create artificial gravity, controlled by retro thrusters on the ship. The 2021 film Stowaway features the upper stage of a launch vehicle connected by 450-meter long tethers to the ship’s main hull, acting as a counterweight for inertia-based artificial gravity.[23]

Linear acceleration[edit]

Linear acceleration is another method of generating artificial gravity, by using the thrust from a spacecraft’s engines to create the illusion of being under a gravitational pull. A spacecraft under constant acceleration in a straight line would have the appearance of a gravitational pull in the direction opposite to that of the acceleration, as the thrust from the engines would cause the spacecraft to «push» itself up into the objects and persons inside of the vessel, thus creating the feeling of weight. This is because of Newton’s third law: the weight that one would feel standing in a linearly accelerating spacecraft would not be a true gravitational pull, but simply the reaction of oneself pushing against the craft’s hull as it pushes back. Similarly, objects that would otherwise be free-floating within the spacecraft if it were not accelerating would «fall» towards the engines when it started accelerating, as a consequence of Newton’s first law: the floating object would remain at rest, while the spacecraft would accelerate towards it, and appear to an observer within that the object was «falling».

To emulate artificial gravity on Earth, spacecraft using linear acceleration gravity may be built similar to a skyscraper, with its engines as the bottom «floor». If the spacecraft were to accelerate at the rate of 1 g—Earth’s gravitational pull—the individuals inside would be pressed into the hull at the same force, and thus be able to walk and behave as if they were on Earth.

This form of artificial gravity is desirable because it could functionally create the illusion of a gravity field that is uniform and unidirectional throughout a spacecraft, without the need for large, spinning rings, whose fields may not be uniform, not unidirectional with respect to the spacecraft, and require constant rotation. This would also have the advantage of relatively high speed: a spaceship accelerating at 1 g, 9.8 m/s2, for the first half of the journey, and then decelerating for the other half, could reach Mars within a few days.[24] Similarly, a hypothetical space travel using constant acceleration of 1 g for one year would reach relativistic speeds and allow for a round trip to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri. As such, low-impulse but long-term linear acceleration has been proposed for various interplanetary missions. For example, even heavy (100 ton) cargo payloads to Mars could be transported to Mars in 27 months and retain approximately 55 percent of the LEO vehicle mass upon arrival into a Mars orbit, providing a low-gravity gradient to the spacecraft during the entire journey.[25]

This form of gravity is not without challenges, however. At present, the only practical engines that could propel a vessel fast enough to reach speeds comparable to Earth’s gravitational pull require chemical reaction rockets, which expel reaction mass to achieve thrust, and thus the acceleration could only last for as long as a vessel had fuel. The vessel would also need to be constantly accelerating and at a constant speed to maintain the gravitational effect, and thus would not have gravity while stationary, and could experience significant swings in g-forces if the vessel were to accelerate above or below 1 g. Further, for point-to-point journeys, such as Earth-Mars transits, vessels would need to constantly accelerate for half the journey, turn off their engines, perform a 180° flip, reactivate their engines, and then begin decelerating towards the target destination, requiring everything inside the vessel to experience weightlessness and possibly be secured down for the duration of the flip.

A propulsion system with a very high specific impulse (that is, good efficiency in the use of reaction mass that must be carried along and used for propulsion on the journey) could accelerate more slowly producing useful levels of artificial gravity for long periods of time. A variety of electric propulsion systems provide examples. Two examples of this long-duration, low-thrust, high-impulse propulsion that have either been practically used on spacecraft or are planned in for near-term in-space use are Hall effect thrusters and Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rockets (VASIMR). Both provide very high specific impulse but relatively low thrust, compared to the more typical chemical reaction rockets. They are thus ideally suited for long-duration firings which would provide limited amounts of, but long-term, milli-g levels of artificial gravity in spacecraft.[citation needed]

In a number of science fiction plots, acceleration is used to produce artificial gravity for interstellar spacecraft, propelled by as yet theoretical or hypothetical means.

This effect of linear acceleration is well understood, and is routinely used for 0 g cryogenic fluid management for post-launch (subsequent) in-space firings of upper stage rockets.[26]

Roller coasters, especially launched roller coasters or those that rely on electromagnetic propulsion, can provide linear acceleration «gravity», and so can relatively high acceleration vehicles, such as sports cars. Linear acceleration can be used to provide air-time on roller coasters and other thrill rides.

Simulating lunar gravity[edit]

In January 2022 China was reported by the South China Morning Post to have built a small (60 centimetres (24 in) diameter) research facility to simulate low lunar gravity with the help of magnets.[27][28] The facility was reportedly partly inspired by the work of Andre Geim (who later shared the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics for his research on graphene) and Michael Berry, who both shared the Ig Nobel Prize in Physics in 2000 for the magnetic levitation of a frog.[27][28]

Simulating microgravity[edit]

Parabolic flight[edit]

Weightless Wonder is the nickname for the NASA aircraft that flies parabolic trajectories. Briefly, it provides a nearly weightless environment to train astronauts, conduct research, and film motion pictures. The parabolic trajectory creates a vertical linear acceleration that matches that of gravity, giving zero-g for a short time, usually 20–30 seconds, followed by approximately 1.8g for a similar period. The nickname Vomit Comet is also used to refer to motion sickness that aircraft passengers often experience during these parabolic trajectories. Such reduced gravity aircraft are nowadays operated by several organizations worldwide.[citation needed]

Neutral buoyancy[edit]

The Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) is an astronaut training facility at the Sonny Carter Training Facility at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.[29] The NBL is a large indoor pool of water, the largest in the world,[30] in which astronauts may perform simulated EVA tasks in preparation for space missions. The NBL contains full-sized mock-ups of the Space Shuttle cargo bay, flight payloads, and the International Space Station (ISS).[31]

The principle of neutral buoyancy is used to simulate the weightless environment of space.[29] The suited astronauts are lowered into the pool using an overhead crane and their weight is adjusted by support divers so that they experience no buoyant force and no rotational moment about their center of mass.[29] The suits worn in the NBL are down-rated from fully flight-rated EMU suits like those in use on the space shuttle and International Space Station.

The NBL tank is 202 feet (62 m) in length, 102 feet (31 m) wide, and 40 feet 6 inches (12.34 m) deep, and contains 6.2 million gallons (23.5 million liters) of water.[31][32] Divers breathe nitrox while working in the tank.[33][34]

Neutral buoyancy in a pool is not weightlessness, since the balance organs in the inner ear still sense the up-down direction of gravity. Also, there is a significant amount of drag presented by water.[35] Generally, drag effects are minimized by doing tasks slowly in the water. Another difference between neutral buoyancy simulation in a pool and actual EVA during spaceflight is that the temperature of the pool and the lighting conditions are maintained constant.

Speculative or fictional mechanisms[edit]

In science fiction, artificial gravity (or cancellation of gravity) or «paragravity»[36][37] is sometimes present in spacecraft that are neither rotating nor accelerating. At present, there is no confirmed technique as such that can simulate gravity other than actual mass or acceleration. There have been many claims over the years of such a device. Eugene Podkletnov, a Russian engineer, has claimed since the early 1990s to have made such a device consisting of a spinning superconductor producing a powerful «gravitomagnetic field», but there has been no verification or even negative results from third parties. In 2006, a research group funded by ESA claimed to have created a similar device that demonstrated positive results for the production of gravitomagnetism, although it produced only 0.0001 g.[38] This result has not been replicated.

See also[edit]

- Non-inertial reference frame – Reference frame that undergoes acceleration with respect to an inertial frame

- Anti-gravity – Idea of creating a place or object that is free from the force of gravity

- Gravitational shielding – Hypothetical shielding of an object from gravity

- Coriolis effect – Force on objects moving within a reference frame that rotates with respect to an inertial frame

- Centrifuge Accommodations Module – Cancelled element of the International Space Station

- Fictitious force – Force on objects moving within a reference frame that rotates with respect to an inertial frame.

- Rotating wheel space station

- Space habitat – Type of space station, intended as a permanent settlement

- Space travel under constant acceleration – Proposed mode of space travel

- Stanford torus – Proposed NASA design for space habitat

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Young, Laurence; Yajima, Kazuyoshi; Paloski, William, eds. (September 2009). ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY RESEARCH TO ENABLE HUMAN SPACE EXPLORATION (PDF). International Academy of Astronautics. ISBN 978-2-917761-04-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Strauss, Samuel (July 2008). «Space medicine at the NASA-JSC, neutral buoyancy laboratory». Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 79 (7): 732–733. ISSN 0095-6562. LCCN 75641492. OCLC 165744230. PMID 18619137.

- ^ a b c Feltman, Rachel (3 May 2013). «Why Don’t We Have Artificial Gravity?». Popular Mechanics. ISSN 0032-4558. OCLC 671272936. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Clément, Gilles R.; Bukley, Angelia P.; Paloski, William H. (June 17, 2015). «Artificial gravity as a countermeasure for mitigating physiological deconditioning during long-duration space missions». Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 9: 92. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2015.00092. ISSN 1662-5137. PMC 4470275. PMID 26136665.

- ^ Fifth Symposium on the Role of the Vestibular Organs in Space Exploration: Held Under the Auspices of the Committee on Hearing, Bioacoustics, and Biomechanics, National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, and Assisted by the Office of Advanced Research and Technology, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1973. p. 25.

- ^ Davis, Bl; Cavanagh, Pr; Perry, Je (September 1994). «Locomotion in a rotating space station: a synthesis of new data with established concepts». Gait & Posture. 2 (3): 157–165. doi:10.1016/0966-6362(94)90003-5. PMID 11539277.

- ^ a b Larson, Carl Alfred (1969). Rotating Space Station Stabilization Criteria for Artificial Gravity. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ Hecht, H.; Brown, E. L.; Young, L. R.; et al. (June 2–7, 2002). «Adapting to artificial gravity (AG) at high rotational speeds». Life in Space for Life on Earth. Proceedings of «Life in space for life on Earth». 8th European Symposium on Life Sciences Research in Space. 23rd Annual International Gravitational Physiology Meeting. 23 (1): P1-5. Bibcode:2002ESASP.501..151H. PMID 14703662.

- ^ Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Manned Spacecraft, Second Revision. New York, NY, USA: MacMillan. pp. 180–182. ISBN 978-0-02-542820-1.

- ^ Clément G, Bukley A (2007) Artificial Gravity. Springer: New York

- ^ a b «Artificial Gravity as a Countermeasure for Mitigating Physiological Deconditioning During Long-Duration Space Missions». June 17, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ «Weightlessness Obstacle to Space Survival». The Science News-Letter. 86 (7): 103. April 4, 1964. JSTOR 3947769.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (April 24, 2017). «Astronaut Peggy Whitson Sets NASA Record For Most Days In Space». NPR. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c David, Leonard (April 4, 1992). «Artificial Gravity and Space Travel». BioScience. 42 (3): 155–159. doi:10.2307/1311819. JSTOR 1311819.

- ^ «Prolonged space travel causes brain and eye abnormalities in astronauts».

- ^ Craig H. Williams; Leonard A. Dudzinski; Stanley K. Borowski; Albert J. Juhasz (March 2005). «Realizing «2001: A Space Odyssey»: Piloted Spherical Torus Nuclear Fusion Propulsion» (PDF). Cleveland, Ohio: NASA. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ a b NAUTILUS – X: Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle Archived March 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Mark L. Holderman, Future in Space Operations (FISO) Colloquium, 2011-01-26. Retrieved 2011-01-31

- ^

NASA NAUTILUS-X: multi-mission exploration vehicle includes a centrifuge, which would be tested at ISS Archived February 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, RLV and Space Transport News, 2011-01-28. Retrieved 2011-01-31 - ^ «NSS Review: The Case for Mars». www.nss.org. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ http://members.marssociety.org/TMQ/TMQ-V1-I1.pdf pg15-Tom Hill

- ^ Korzun, Ashley M.; Wagner, Erika B.; et al. (2007). Mars Gravity Biosatellite: Engineering, Science, and Education. 58th International Astronautical Congress.

- ^ «The Mars Gravity Biosatellite Program Is Closing Down». www.spaceref.com. June 24, 2009. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Kiang, Jessica (April 22, 2021). «Review: Anna Kendrick is lost, and found, in space in smart sci-fi ‘Stowaway’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Clément, Gilles; Bukley, Angelia P. (2007). Artificial Gravity. Springer New York. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-387-70712-9. Extract of page 35

- ^ VASIMR VX-200 Performance and Near-term SEP Capability for Unmanned Mars Flight Archived March 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Tim Glover, Future in Space Operations (FISO) Colloquium, pp. 22, 25, 2011-01-19. Retrieved 2011-02-01

- ^ Jon Goff; et al. (2009). «Realistic Near-Term Propellant Depots» (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

Developing techniques for manipulating fluids in microgravity, which typically fall into the category known as settled propellant handling. Research for cryogenic upper stages dating back to the Saturn S-IVB and Centaur found that providing a slight acceleration (as little as 10−4 to 10−5 g of acceleration) to the tank can make the propellants assume a desired configuration, which allows many of the main cryogenic fluid handling tasks to be performed in a similar fashion to terrestrial operations. The simplest and most mature settling technique is to apply thrust to the spacecraft, forcing the liquid to settle against one end of the tank.

- ^ a b «China building «Artificial Moon» that simulates low gravity with magnets». Futurism.com. Recurrent Ventures. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

Interestingly, the facility was partly inspired by previous research conducted by Russian physicist Andrew Geim in which he floated a frog with a magnet. The experiment earned Geim the Ig Nobel Prize in Physics, a satirical award for unusual scientific research. It’s cool that a quirky experiment involving floating a frog could lead to something approaching an honest-to-God antigravity chamber.

- ^ a b Chen, Stephen (January 12, 2022). «China has built an artificial moon that simulates low-gravity conditions on Earth». South China Morning Post. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

It is said to be the first of its kind and could play a key role in the country’s future lunar missions. The magnetic field supported the landscape and was inspired by experiments to levitate a frog.

- ^ a b c Strauss, S. (July 2008). «Space medicine at the NASA-JSC, neutral buoyancy laboratory». Aviat Space Environ Med. 79 (7): 732–3. PMID 18619137.

- ^ «Behind the scenes training». NASA. May 30, 2003. Archived from the original on November 24, 2002. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Strauss, S.; Krog, R.L.; Feiveson, A.H. (May 2005). «Extravehicular mobility unit training and astronaut injuries». Aviat Space Environ Med. 76 (5): 469–74. PMID 15892545. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ «NBL Characteristics». About the NBL. NASA. June 23, 2005. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007.

- ^ Fitzpatrick DT, Conkin J (2003). «Improved pulmonary function in working divers breathing nitrox at shallow depths». Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine. 30 (Supplement): 763–7. PMID 12862332. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Fitzpatrick DT, Conkin J (July 2003). «Improved pulmonary function in working divers breathing nitrox at shallow depths». Aviat Space Environ Med. 74 (7): 763–7. PMID 12862332. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ Pendergast D, Mollendorf J, Zamparo P, Termin A, Bushnell D, Paschke D (2005). «The influence of drag on human locomotion in water». Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine. 32 (1): 45–57. PMID 15796314. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Collision Orbit, 1942 by Jack Williamson

- ^ Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space by Carl Sagan, Chapter 19

- ^ «Toward a new test of general relativity?». Esa.int. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

External links[edit]

- List of peer review papers on artificial gravity

- TEDx talk about artificial gravity

- Revolving artificial gravity calculator

- Overview of artificial gravity in Sci-Fi and Space Science

- NASA’s Java simulation of artificial gravity

- Variable Gravity Research Facility (xGRF), concept with tethered rotating satellites, perhaps a Bigelow expandable module and a spent upper stage as a counterweight

Даже человек, не интересующийся космосом, хоть раз видел фильм о космических путешествиях или читал о таких вещах в книгах. Практически во всех подобных произведениях люди ходят по кораблю, нормально спят, не испытывают проблем с приемом пищи. Это означает, что на этих – выдуманных – кораблях имеется искусственная гравитация. Большинство зрителей воспринимает это как нечто совершенно естественное, а ведь это совсем не так.

Искусственная гравитация

Так называют изменение (в любую сторону) привычной для нас гравитации путем применения различных способов. И делается это не только в фантастических произведениях, но и во вполне реальных земных ситуациях, чаще всего, для экспериментов.

В теории создание искусственной гравитации выглядит не так сложно. К примеру, воссоздать ее можно при помощи инерции, точнее, центробежной силы. Потребность в этой силе возникла не вчера – произошло это сразу, как только человек начал мечтать о длительных космических перелетах. Создание искусственной гравитации в космосе даст возможность избежать множества проблем, возникающих при продолжительном нахождении в невесомости. У космонавтов слабеют мускулы, кости становятся менее прочными. Путешествуя в таких условиях месяцы, можно получить атрофию некоторых мышц.

Таким образом, на сегодняшний день создание искусственной гравитации – задача первостепенной важности, освоение космоса без этого умения просто невозможно.

Матчасть

Даже те, кто знают физику лишь на уровне школьной программы, понимают, что гравитация – один из фундаментальных законов нашего мира: все тела взаимодействуют друг с другом, испытывая взаимное притяжение/отталкивание. Чем больше тело, тем выше его сила притяжения.

Земля для нашей реальности — объект очень массивный. Именно поэтому все без исключения тела вокруг к ней притягиваются.

Для нас это означает ускорение свободного падения, которое принято измерять в g, равное 9.8 метра за квадратную секунду. Это значит, что если бы под ногами у нас не было опоры, мы бы падали со скоростью, ежесекундно увеличивающейся на 9.8 метра.

Таким образом, только благодаря гравитации мы способны стоять, падать, нормально есть и пить, понимать, где находится верх, где низ. Если притяжение исчезнет – мы окажемся в невесомости.

Особенно хорошо знакомы с этим феноменом космонавты, оказывающиеся в космосе в состоянии парения – свободного падения.

Теоретически ученые знают, как создать искусственную гравитацию. Существует несколько методик.

Большая масса

Самый логичный вариант – сделать космический корабль настолько большим, чтобы на нем возникала искусственная гравитация. На корабле можно будет чувствовать себя комфортно, поскольку не будет потеряна ориентация в пространстве.

К сожалению, этот способ при современном развитии технологий нереален. Чтобы соорудить такой объект, требуется слишком много ресурсов. Кроме того, для его подъема потребуется невероятное количество энергии.

Ускорение

Казалось бы, если требуется достичь g, равного земному, нужно всего лишь придать кораблю плоскую (платформообразную) форму, и заставить его двигаться по перпендикуляру к плоскости с нужным ускорением. Таким путем будет получена искусственная гравитация, причем – идеальная.

Однако в реальности все гораздо сложнее.

В первую очередь стоит учесть топливный вопрос. Для того чтобы станция постоянно ускорялась, необходимо иметь бесперебойный источник питания. Даже если внезапно появится двигатель, не выбрасывающий материю, закон сохранения энергии останется в силе.

Вторая проблема заключается в самой идее постоянного ускорения. Согласно нашим знаниям и физическим законам, невозможно ускоряться до бесконечности.

Кроме того, такой транспорт не подходит для исследовательских миссий, поскольку он должен постоянно ускоряться – лететь. Он не сможет остановиться для изучения планеты, он даже медленно пролететь вокруг нее не сможет – надо ускоряться.

Таким образом, становится ясно, что и такая искусственная гравитация нам пока недоступна.

Карусель

Каждый знает, как вращение карусели воздействует на тело. Поэтому устройство искусственной гравитации по этому принципу кажется наиболее реальным.

Все, что находится в диаметре карусели, стремится выпасть из нее со скоростью, примерно равной скорости вращения. Выходит, что на тела действует сила, направленная вдоль радиуса вращающегося объекта. Это очень похоже на гравитацию.

Итак, требуется корабль, имеющий цилиндрическую форму. При этом он должен вращаться вокруг своей оси. Между прочим, искусственная гравитация на космическом корабле, созданная по этому принципу, достаточно часто демонстрируется в научно-фантастических фильмах.

Бочкообразный корабль, вращаясь вокруг продольной оси, создает центробежную силу, направление которой соответствует радиусу объекта. Чтобы вычислить получаемое ускорение, требуется разделить силу на массу.

Знающим физику людям посчитать это будет совсем не сложно: a = ω²R.

В этой формуле результат расчетов – ускорение, первая переменная – узловая скорость (измеряется в количестве радиан в секунду), вторая – радиус.

Согласно этому, для получения привычной нам g, необходимо грамотно сочетать угловую скорость и радиус космического транспорта.

Подобная проблема освещена в таких фильмах, как «Интерсолах», «Вавилон 5», «2001 год: Космическая одиссея» и подобных им. Во всех этих случаях искусственная гравитация приближена к земному ускорению свободного падения.

Как бы ни была хороша идея, реализовать ее достаточно сложно.

Проблемы метода «карусель»

Самая очевидная проблема освещена в «Космической одиссее». Радиус «космического перевозчика» составляет порядка 8 метров. Для того чтобы получить ускорение в 9.8, вращение должно происходить со скоростью, примерно, 10.5 оборота ежеминутно.

При указанных величинах проявляется «эффект Кориолиса», который заключается в том, что на различном удалении от пола действует разная сила. Она напрямую зависит от угловой скорости.

Выходит, искусственная гравитация в космосе создана будет, однако слишком быстрое вращение корпуса приведет к проблемам с внутренним ухом. Это, в свою очередь, вызывает нарушения равновесия, проблемы с вестибулярным аппаратом и прочие – аналогичные – трудности.

Возникновение этой преграды говорит о том, что подобная модель крайне неудачная.

Можно попробовать пойти от обратного, как поступили в романе «Мир-Кольцо». Тут корабль выполнен в форме кольца, радиус которого приближен к радиусу нашей орбиты (порядка 150 млн км). При таком размере скорости его вращения вполне достаточно, чтобы игнорировать эффект Кориолиса.

Можно предположить, что проблема решена, однако это совсем не так. Дело в том, что полный оборот этой конструкции вокруг своей оси занимает 9 дней. Это дает возможность предположить, что нагрузки окажутся слишком велики. Для того чтобы конструкция их выдержала, необходим очень крепкий материал, которым на сегодняшний день мы не располагаем. Кроме того, проблемой является количество материала и непосредственно процесс постройки.

В играх подобной тематики, как и в фильме «Вавилон 5», эти проблемы каким-то образом решены: вполне достаточна скорость вращения, эффект Кориолиса не существенен, гипотетически создать такой корабль возможно.

Однако даже такие миры имеют недостаток. Зовут его – момент импульса.

Корабль, вращаясь вокруг оси, превращается в огромный гироскоп. Как известно, заставить гироскоп отклониться от оси крайне сложно благодаря моменту импульса. Важно, чтобы его количество не покидало систему. Это означает, что задать направление этому объекту будет очень сложно. Однако такую проблему решить можно.

Решение проблемы

Искусственная гравитация на космической станции становится доступной, когда на помощь приходит «цилиндр О’Нила». Для создания этой конструкции необходимы одинаковые цилиндрические корабли, которые соединяют вдоль оси. Вращаться они должны в разные стороны. Результатом такой сборки является нулевой момент импульса, поэтому не должно возникнуть трудностей с приданием кораблю необходимого направления.

Если возможно сделать корабль радиусом порядка 500 метров, то он будет работать именно так, как и должен. При этом искусственная гравитация в космосе будет вполне комфортной и пригодной для длительных перелетов на кораблях или исследовательских станциях.

Space Engineers

Как создать искусственную гравитацию, известно создателям игры. Впрочем, в этом фантастическом мире гравитация – это не взаимное притяжение тел, но линейная сила, призванная ускорить предметы в заданном направлении. Притяжение тут не абсолютно, оно изменяется при перенаправлении источника.

Искусственная гравитация на космической станции создается путем использования специального генератора. Она равномерна и равнонаправленна в зоне действия генератора. Так, в реальном мире, попав под корабль, в котором установлен генератор, вы бы были притянуты к корпусу. Однако в игре герой будет падать до тех пор, пока не покинет периметр действия устройства.

На сегодняшний день искусственная гравитация в космосе, созданная таким устройством, для человечества недоступна. Однако даже убеленные сединами разработчики не перестают мечтать о ней.

Сферический генератор

Это более реалистичный вариант оборудования. При его установке гравитация имеет направление к генератору. Это дает возможность создать станцию, гравитация которой будет равна планетарной.

Центрифуга

Сегодня искусственная гравитация на Земле встречается в различных устройствах. Основаны они, большей частью, на инерции, поскольку эта сила ощущается нами аналогично гравитационному воздействию – организм не различает, какая причина вызывает ускорение. Как пример: человек, поднимающийся в лифте, испытывает на себе воздействие инерции. Глазами физика: подъем лифта добавляет к ускорению свободного падения ускорение кабины. При возвращении кабины к размеренному движению «прибавка» в весе исчезает, возвращая привычные ощущения.

Ученых давно интересует искусственная гравитация. Центрифуга используется для этих целей чаще всего. Этот метод подходит не только для космических кораблей, но и для наземных станций, в которых требуется изучать воздействие гравитации на человеческий организм.

Изучить на Земле, применять в…

Хотя изучение гравитации началось из космоса, это очень земная наука. Даже на сегодняшний день достижения в этой сфере нашли свое применение, например, в медицине. Зная, возможно ли создать искусственную гравитацию на планете, можно использовать ее для лечения проблем с двигательным аппаратом или нервной системы. Более того, изучением этой силы занимаются прежде всего на Земле. Это дает возможность космонавтам проводить эксперименты, оставаясь под пристальным вниманием врачей. Другое дело искусственная гравитация в космосе, там нет людей, способных помочь космонавтам при возникновении непредвиденной ситуации.

Имея в виду полную невесомость, нельзя брать в расчет спутник, находящийся на околоземной орбите. На эти объекты, пусть и в малой степени, воздействует земное притяжение. Силу тяжести, образующуюся в таких случаях, называют микрогравитацией. Реальную гравитацию испытывают только в аппарате, летящем с постоянной скоростью в открытом космосе. Впрочем, человеческий организм эту разницу не ощущает.

Испытать на себе невесомость можно при затяжном прыжке (до того, как купол раскроется) или во время параболического снижения самолета. Такие эксперименты часто ставят в США, но в самолете это ощущение длится только 40 секунд – это слишком мало для полноценного изучения.

В СССР еще в 1973 году знали, можно ли создать искусственную гравитацию. И не просто создавали ее, но и в некотором роде изменяли. Яркий пример искусственного уменьшения силы тяжести – сухое погружение, иммерсия. Для достижения необходимого эффекта требуется положить плотную пленку на поверхность воды. Человек размещается поверх нее. Под тяжестью тела организм погружается под воду, наверху остается лишь голова. Эта модель демонстрирует безопорность с пониженной гравитацией, которая характерна для океана.

Нет необходимости отправляться в космос, чтобы ощутить на себе воздействие противоположной невесомости силы – гипергравитации. При взлете и посадке космического корабля, в центрифуге перегрузку можно не только ощутить, но и изучить.

Лечение гравитацией

Гравитационная физика изучает в том числе и воздействие невесомости на организм человека, стремясь минимизировать последствия. Однако большое количество достижений этой науки способно пригодиться и обычным жителям планеты.

Большие надежды медики возлагают на исследования поведения мышечных ферментов при миопатии. Это тяжелое заболевание, ведущее к ранней смерти.

При активных физических занятиях в кровь здорового человека поступает большой объем фермента креатинофосфокиназы. Причина этого явления неясна, возможно, нагрузка воздействует на мембрану клеток таким образом, что она «дырявится». Больные миопатией получают тот же эффект без нагрузок. Наблюдения за космонавтами показывают, что в невесомости поступление активного фермента в кровь значительно снижается. Такое открытие позволяет предположить, что применение иммерсии позволит снизить негативное воздействие приводящих к миопатии факторов. В данный момент проводятся опыты на животных.

Лечение некоторых болезней уже сегодня проводится с использованием данных, полученных при изучении гравитации, в том числе искусственной. К примеру, проводится лечение ДЦП, инсультов, Паркинсона путем применения нагрузочных костюмов. Практически закончены исследования положительного воздействия опоры – пневматического башмака.

Полетим ли на Марс?

Последние достижения космонавтов дают надежду на реальность проекта. Имеется опыт медицинской поддержки человека при длительном нахождении вдали от Земли. Много пользы принесли и исследовательские полеты к Луне, сила гравитации на которой в 6 раз меньше нашей родной. Теперь космонавты и ученые ставят перед собой новую цель – Марс.

Прежде чем вставать в очередь за билетом на Красную планету, следует знать, что ожидает организм уже на первом этапе работы – в пути. В среднем дорога к пустынной планете займет полтора года – около 500 суток. Рассчитывать в пути придется только на свои собственные силы, помощи ждать просто неоткуда.

Подтачивать силы будут множество факторов: стресс, радиация, отсутствие магнитного поля. Самое главное же испытание для организма – изменение гравитации. В путешествии человек «ознакомится» с несколькими уровнями гравитации. В первую очередь это перегрузки при взлете. Затем – невесомость во время полета. После этого – гипогравитация в месте назначения, т. к. сила тяжести на Марсе менее 40% земной.

Как справляются с отрицательным воздействием невесомости в длительном перелете? Есть надежда, что разработки в области создания искусственной гравитации помогут решить этот вопрос в недалеком будущем. Опыты на крысах, путешествующих на «Космос-936» показывают, что этот прием не решает всех проблем.

Опыт ОС показал, что гораздо больше пользы для организма способно принести применение тренажерных комплексов, способных определить необходимую нагрузку для каждого космонавта индивидуально.

Пока считается, что на Марс полетят не только исследователи, но и туристы, желающие основать колонию на Красной планете. Для них, во всяком случае первое время, ощущения от нахождения в невесомости перевесят все доводы медиков о вреде длительного нахождения в таких условиях. Однако через несколько недель помощь потребуется и им, поэтому так важно суметь найти способ создать на космическом корабле искусственную гравитацию.

Итоги

Какие выводы можно сделать о создании искусственной гравитации в космосе?

Среди всех рассматриваемых в данный момент вариантов наиболее реалистично выглядит вращающаяся конструкция. Однако при нынешнем понимании физических законов это невозможно, поскольку корабль – это не полый цилиндр. Внутри него имеются перекрытия, мешающие воплощению идей.

Кроме того, радиус корабля должен быть настолько большим, чтобы эффект Кориолиса не оказывал существенного влияния.

Чтобы управлять чем-то подобным, требуется упомянутый выше цилиндр О’Нила, который даст возможность управлять кораблем. В этом случае повышаются шансы применения подобной конструкции для межпланетных перелетов с обеспечением команды комфортным уровнем гравитации.

До того как человечеству удастся претворить свои мечты в жизнь, хотелось бы видеть в фантастических произведениях чуточку большей реалистичности и еще большего знания законов физики.

-

-

masterok Golden Entry

October 19 2020, 10:00

- Технологии

- Космос

- Кино

- Фантастика

- Cancel

Существуют ли технологии искусственной гравитации?

В научно-фантастических фильмах, где корабль летит к далекой галактике, экипаж внутри в большинстве случаев находится не в невесомости, а спокойно передвигается по полу. Это возможно благодаря работающей системе искусственной гравитации, которая создает силу притяжения.

Но существуют ли подобные технологии в реальной жизни?

Как создать искусственную гравитацию?

Существует два способа создания искусственной гравитации. Однако реализовать их довольно тяжело с технической точки зрения.

Первый метод основан на центробежной силе, которая преобразовывается в притяжение. Для этого космический корабль должен быть выполнен в виде круга и постоянно вращаться. В момент передвижения модули, установленные на кольце, будут притягиваться к центру. Из-за этого внутри помещений будет создаваться искусственная гравитация.