Леонардо да Винчи (1452-1519) известен созданием некоторых из величайших произведений искусства. Но помимо того, что он был блестящим художником, Леонардо был также ученым, инженером и изобретателем. И чертовски хорошим, что ясно демонстрируют его невероятные прототипы заложившие основу для самых инновационных изобретений в последнее время.

Невероятные изобретения Леонардо да Винчи

1. Робот-рыцарь

Известно, что Леонардо с детства очень увлекался анатомией. Наверняка именно она, а также огромное желание помочь человечеству способствовали появлению данной технологии примерно в 1495 году. Подолгу да Винчи изучал человеческое тело и решил создать свой собственный механический прототип человека (мог приподниматься и садиться, двигать руками и шеей), естественно, отличающийся от современных киборгов. Но, именно он является первоисточником для дальнейших совершенствований робототехники.

2. Воздушный винт

Это прототип современного вертолёта, у которого были «лопасти» и если придать им достаточной скорости то формировалось аэродинамическое давление, благодаря которому он мог взлететь. При наличии воздуха под лопастями воздушный винт поднимался на достаточно высокое расстояние, но лететь самостоятельно не мог. Винт должен был, приводился в движение людьми, которые шли вокруг оси и толкали рычаги.

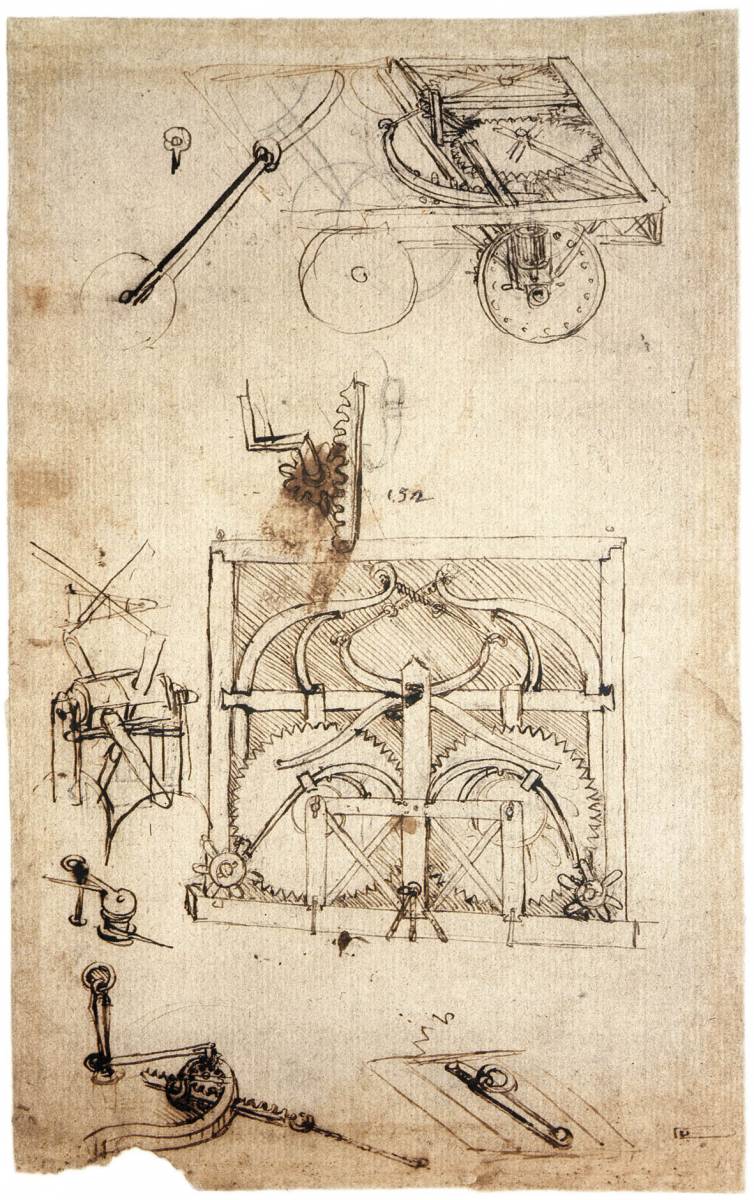

3. Самоходная тележка

Самоходная тележка очень похожа, и по сути дела, является предком нашего автомобиля. Она была изобретена да Винчи таким образом, что могла передвигаться как с водителем, так и без — своего рода «машина-робот». К сожалению, учёным не удалось детально изучить конструкцию, благодаря которому передвигалась машина, но они сделали предположение, что это был пружинный механизм. Он прятался внутри самой телеги, его необходимо было заводить рукой, после чего пружина разматывалась и телега двигалась.

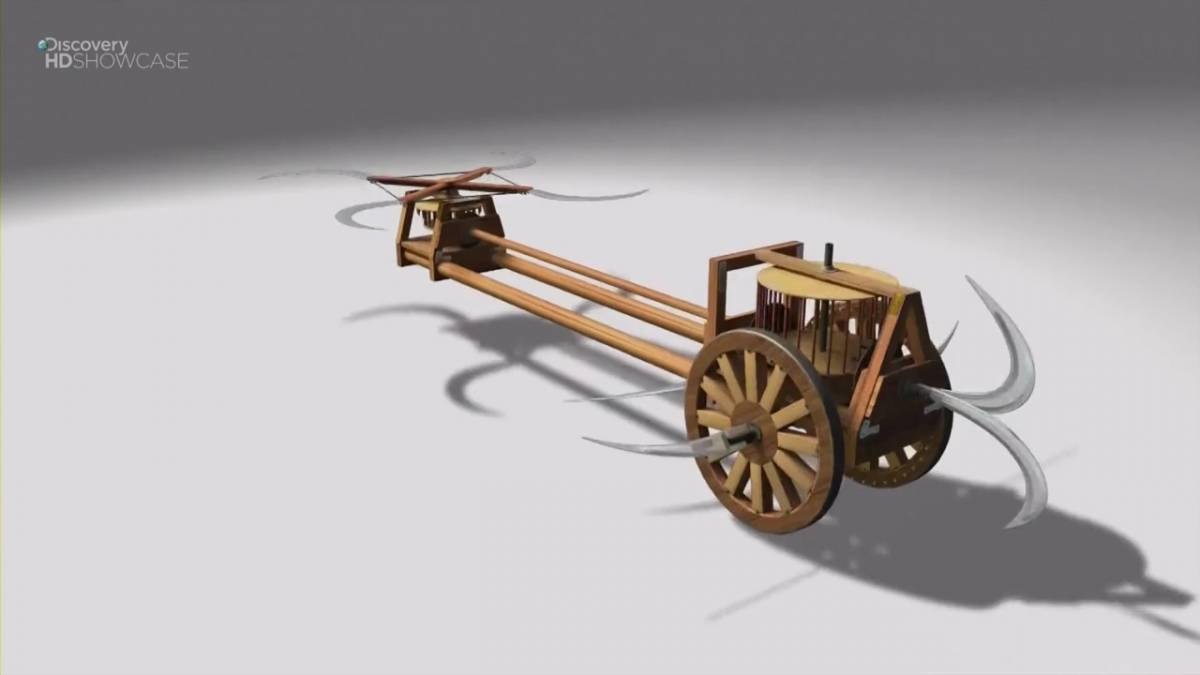

4. Танк/Бронированная машина

Данное изобретение считается прототипом современных танков. Представляло собой конической формы машину по периметру оснащённую пушками. Могла перемещаться посредством мускульной силы экипажа из восьми человек. Скорее всего, предназначалась для запугивания противника, а не для использования в качестве серьёзного военного оружия.

5. Водолазный костюм

Водолазный костюм был изобретён для подводных диверсий. Чтоб водолазы могли, переодевшись в это одеяние вскрывать днища вражеских судов, которые приплывали в Венецию. Костюм был выполнен из кожи. Дышать ныряльщики могли с помощью гибкой дыхательной трубки, сделанной из кусков тростника прикреплённой к винным бутылям или плавучему колоколу на поверхности.

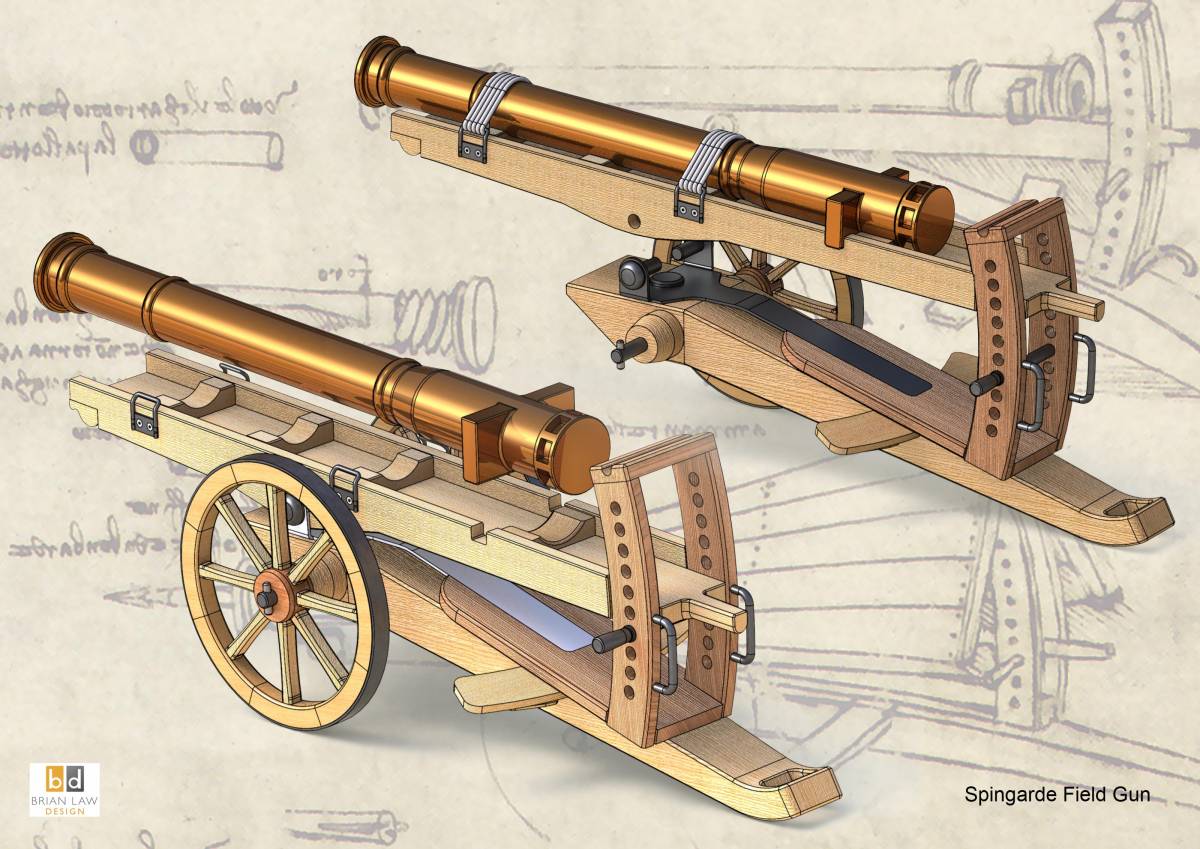

6. Пулемёт

Леонардо да Винчи предложил собрать вместе 11 мушкетов на одной прямоугольной платформе, после этого сложить в треугольник три платформы и поместить вовнутрь вал. Подразумевалось, что пока один ряд мушкетов стрелял, два других бы остывали и перезаряжались. Как известно, не одно из изобретений да Винчи для убийств не было построено, но если бы этот пулемёт был сооружён, то он был крайне губителен для противника.

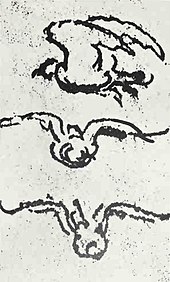

7. Крылатый летательный аппарат (Орнитоптер)

Не секрет, что Леонардо да Винчи интересовало все что летает, потому итальянский изобретатель разработал орнитоптер, устройство, с помощью которого можно подниматься в воздух и летать, словно птица, размахивая механическими крыльями, приводимыми в движение силой мышц. С точки зрения аэродинамики этот прибор был весьма успешен и учёные доказали, будь он построен, человек бы и правда взлетел!

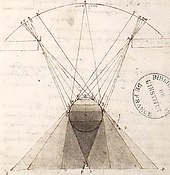

8. Парашют

В 1483 году Леонардо да Винчи нарисовал эскиз пирамидального парашюта — «палатки» из накрахмаленного полотна размером 12х12 локтей. Как он сам обозначал, благодаря данному устройству человек мог упасть с любой высоты при этом не повредиться. Удивительно то, что эти расчёты близки к размерам современного парашюта.

9. Подшипник

Пожалуй, величайшим изобретением Леонардо да Винчи считается подшипник. Этот механизм настолько маленький, что мы просто не замечаем его в повседневной жизни, но и представить себе наш быт без него невозможно! Подшипник являлся частью большинства изобретённых механизмов Леонардо, именно он основа практически каждого подвижного механизма и сейчас.

Ученый, художник, скульптор, архитектор — это лишь некоторые звания, которые Леонардо ди сер Пьеро да Винчи носил в течение своей 67-летней жизни. Он был человеком, чье любопытство равнялось только его уму и таланту. Многие утверждают, что он был самым умным человеком на свете — настоящим гением. Его таланты во многих областях науки и искусства просто невозможно отрицать. После стольких веков одно можно сказать наверняка: он был единственным в своем роде.

В 2019 году исполнилось 500 лет со дня смерти да Винчи. И хотя прошло уже целых пять столетий, именно его изобретения мы используем по сей день, и многие из его дальновидных проектов заложили основу для инновационных изобретений. Мы собрали знаковые изобретения и открытия Леонардо, которые навсегда изменили мир.

Мона Лиза

Картина, ныне находящаяся в Лувре под пуленепробиваемым стеклом, очаровывает человечество на протяжении веков. Картина представляет собой портрет Лизы Герардини, но на полотне кроется намного больше, чем просто Лиза. Огромное количество теорий, версий, тайн и загадок связано с этим портретом. Говорят, что только на губы у да Винчи ушло 10 лет! Известно впечатляющее количество теорий не только о таинственной улыбке женщины и якобы скрытом сексуальном подтексте картины, но и о том, является ли портрет изображением альтер-эго самого да Винчи, и так далее. Многие видят в Моне Лизе слияние мужских и женских черт, в то время как другие видят в ней четкие черты Девы Марии. Несмотря на то, что Джоконда не является привлекательной в традиционном смысле, ее образ воплощает собой идеальную женщину.

«Мона Лиза» является самой копируемой картиной в мире, и влияние ее на искусство огромно и не теряет своей силы на протяжении веков.

Леонардо да Винчи, Мона Лиза

Фото: www.wikipedia.org

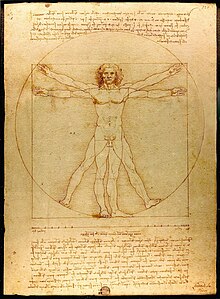

Витрувианский человек

Увлечение анатомией человеческого тела передалось Леонардо от его учителя Андреа дель Верроккьо, который настаивал на том, чтобы все ученики изучали анатомию. В результате да Винчи так увлекся анатомией, что заполнил все свои тетради рисунками мышц и сухожилий. Он вскрыл десятки тел, чтобы создать детальные рисунки скелетов, черепов и костей. Помимо этого, он изучал физиологию, делая восковые формы мозга и сердца, чтобы лучше понять, как кровь течет через сосудистую систему и создавая некоторые из первых рисунков человеческих органов, включая аппендикс, репродуктивные органы и легкие.

Позже да Винчи применил эти знания в одной из своих самых известных работ. Его рисунок «Витрувианского человека» — это модель человеческого тела в идеальных пропорциях. Работа была вдохновлена древнеримским архитектором Витрувием, который, считал, что пропорциональность как у людей должна применяться к проектированию и строительству зданий.

Рисунок Витрувианского человека стал знаковым: его и пояснения к нему часто называют «каноническими пропорциями».

Леонардо да Винчи, Витрувианский человек

Фото: www.wikipedia.org

Мост да Винчи

Да Винчи был блестящим инженером, хотя далеко не все его проекты были осуществлены; некоторые из его идей были вовсе не практичны. Однако многие инженерные идеи были применены и по-прежнему вдохновляют исследователей.

В 2001 году в Норвегии, в поселке Аас, был возведен пешеходный мост по проекту да Винчи. Этот проект, широко известный в наше время как «Мона Лиза среди мостов» был раскритикован современниками да Винчи и признан нежизнеспособным. Да Винчи спроектировал мост в 1502 году, чтобы тот пересек бухту Золотой Рог в Стамбуле. Длиной 346 метров, это был бы самый длинный мост в мире того времени, если бы только султан Баязет II посчитал это строительство возможным.

В итоге спустя 5 веков амбициозный проект пешеходного моста да Винчи был осуществлен в Норвегии — стране с суровым климатом с его ветром, дождями и снегом. Это было партнерство между норвежской администрацией общественных дорог и норвежским художником Вебьерном Сандом, который возглавил проект. Хотя сам да Винчи представлял себе мост в камне, практичные норвежцы сочли этот проект слишком дорогим и остановились на изящной версии из слоистого дерева с параболической аркой. На осуществление проекта потрачено 930 000 фунтов стерлингов.

Мост да Винчи

Фото: www.wikipedia.org

Парашют

Еще более чем за 400 лет до того, как братья Райт взлетели в небо на первом в мире самолете, да Винчи искал и разрабатывал способы для человека подняться в небо. Он изучал строение птиц и летучих мышей, чтобы попытаться создать летательный аппарат, или орнитоптер, в котором человек будет привязан к каркасу с деревянными крыльями. Идея треугольного парашюта на основе деревянных балок длиной 7 метров, покрытыми тканью, стала первым в мире проектом устройства, которое позволило бы людям «прыгать с любой высоты без травм», — как писал он сам. Как и многие другие идеи да Винчи, эта значительно опередила свое время. Технологии помогли развить идеи, раскрытые в наброске 1485 года, до первого практического парашюта лишь к 1783 году.

Многие из монументальных открытий Леонардо никогда не испытывались. Однако все же нашелся смельчак, который решился испытать на себе такой треугольный парашют. Британский скайдайвер Эдриан Николс в 2000 году построил парашют по рисунку Леонардо. Несмотря на скептицизм большинства людей, парашют летел плавно, и Николс успешно приземлился с высоты 2130 метров, тем самым практически доказав, что гений эпохи Возрождения действительно был изобретателем первого рабочего парашюта.

Парашют да Винчи

Фото: www.wikipedia.org

Это были лишь некоторые примеры изобретений и достижений Леонардо да Винчи, которые навсегда изменили историю и жизнь человечества. В следующем материале мы расскажем еще о нескольких важных достижениях гения.

«Универсальный» гений эпохи Возрождения.

Леонардо да Винчи, который родился 15 апреля 1452 года, известен в первую очередь как гениальный художник, нарисовавший «Мону Лизу» и множество других, не менее выдающихся, картин. Но помимо этого да Винчи был также ученым, инженером и изобретателем, пишет History Lists. И чертовски хорошим, что ясно демонстрируют его невероятные изобретения. Вот 9 самых важных из них:

1. Парашют.

Изобретение парашюта традиционно приписывают Леонардо да Винчи, хотя он и не был первым, кто придумал эту концепцию. Эскиз устройства, очень похожего на да Винчи, появляется в рукописи неизвестного автора, и это было прототипом парашюта в форме пирамиды с деревянной рамой, нарисованной Леонардо в знаменитом Кодексе Атлантик.

Более того, есть свидетельства того, что подобные парашютам устройства использовались в Китае еще в 11 веке. Однако парашют Леонардо был более изощренным, и в 2000 году британский парашютист Адриан Николас доказал, что он работает, прыгнув с парашютом, построенным по эскизам да Винчи.

2. Воздушный винт.

Это еще одно изобретение да Винчи, которое больше напоминает технологии 20-го и 21-го веков, чем те, которые использовались во времена Ренессанса. Действительно, его воздушный винт выглядит поразительно похожим на современные вертолеты. И, по словам Леонардо, он мог летать.

Но, по мнению большинства экспертов, было бы невозможно эффективно управлять им, потому что одной мышечной силы недостаточно, чтобы держать машину в воздухе. Несмотря на это, Леонардо часто приписывают идею концепции вертолета или, по крайней мере, концепции вертикального полета.

3. Орнитоптер.

Да Винчи разработал планы для ряда летательных аппаратов, включая орнитоптеры. Вдохновленный полетом птиц и птиц, орнитоптер Леонардо должен был подниматься и управляться взмахами крыльев, которые, в свою очередь, будут «питаться» энергией мышц. Управляемые человеком орнитоптеры способны летать, но только в течение короткого периода времени и на короткие расстояния (несколько сотен метров) из-за ограниченных возможностей человека.

Летательный аппарат Леонардо — если бы он мог летать — работал бы не лучше. Тем не менее, его заметки и наброски демонстрируют глубокое понимание аэродинамики и концепций полета, многие из которых оказались фундаментальными для развития современной авиации.

4. Робот.

То, что построил да Винчи, не было роботом в современном понимании. Он построил автомат с автоматическим управлением, который, однако, мог двигаться без помощи/вмешательства человека.

В середине 1490-х годов известный ученый сконструировал так называемого робота или механического рыцаря Леонардо — гуманоидного автомата, который мог самостоятельно сидеть, стоять и двигать руками. Несколько лет спустя он также построил механического льва, который мог двигаться самостоятельно.

5. Пулемет.

Пулемет Леонардо — 33-ствольный орган — не был похож на современные пулеметы. Вместо того, чтобы быстро стрелять пулями из ленты, он предназначался для стрельбы пулями из отдельных пушек, которые были соединены в три ряда, в каждом из которых было по 11 пушек.

33-ствольный пулемет Леонардо никогда не строился и не использовался в войне, но он примечателен введением концепции современного пулемета. Последний попал на поле битвы только в 19 веке, первоначально в форме скорострельного оружия.

6. Виола Органиста.

Среди множества набросков и рисунков Леонардо есть также так называемая альтистская органиста, которая свидетельствует о многих интересах и талантах знаменитого ренессансного эрудита. Тем не менее, кажется, что он никогда не создавал свой инновационный музыкальный инструмент, который представляет собой разновидность клавесина, играемого на клавиатуре. Подобные инструменты были созданы позже, но не ясно, были ли они вдохновлены альтовой органистой да Винчи или они были разработаны независимо.

7. Гидрокостюм для дайвинга.

Как и в случае с парашютом, да Винчи был не первым, кто предложил идею костюма, который позволял бы его владельцу дышать под водой. Но опять же, его дизайн поразительно похож на ранние прототипы современного гидрокостюма: он состоял из (кожаной) куртки, брюк и шлема со встроенными стеклянными очками и дыхательной трубки, которая снабжала воздух воздухом с поверхности.

И самое главное, он был придуман задолго до современных водолазных костюмов.

8. Самоходная тележка.

Как и многие другие изобретения Леонардо, это намного опередило его время. Это, вероятно, также объясняет, почему невероятная машина была «открыта» на его рисунках только в начале 20-го века. Но никто не мог понять, как это должно было работать вплоть до конца 1990-х годов, когда профессор Карло Педретти понял, что она не приводится в действие непосредственно пружинами, а другим механизмом, который контролируется пружинами.

В дополнение к способности передвигаться самостоятельно, самоходная тележка Леонардо также может быть запрограммирована на поворот — хотя только на правую сторону.

9. Танк/Бронированная машина.

Танк был впервые использован только во время Первой мировой войны (1914-18), но концепция или, по некоторым данным, первый прототип был разработан Леонардо да Винчи более 500 лет назад. Танк/бронетранспортер Леонардо был оборудованным серией орудий/пушек и должен был управляться людьми изнутри.

Тем не менее, конструкция содержала серьезный недостаток, который сделал броневик нерабочим. Большинство историков считают, что да Винчи сделал это преднамеренно. Или он действительно не хотел, чтобы военная машина была построена, в то время как другие думают, что он, возможно, хотел предотвратить попадание дизайна в чужие руки.

Теперь вы понимаете, почему да Винчи считал себя инженером, а не художником?

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was an Italian polymath, regarded as the epitome of the «Renaissance Man», displaying skills in numerous diverse areas of study. Whilst most famous for his paintings such as the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper, Leonardo is also renowned in the fields of civil engineering, chemistry, geology, geometry, hydrodynamics, mathematics, mechanical engineering, optics, physics, pyrotechnics, and zoology.

While the full extent of his scientific studies has only become recognized in the last 150 years, during his lifetime he was employed for his engineering and skill of invention. Many of his designs, such as the movable dikes to protect Venice from invasion, proved too costly or impractical. Some of his smaller inventions entered the world of manufacturing unheralded. As an engineer, Leonardo conceived ideas vastly ahead of his own time, conceptually inventing the parachute, the helicopter, an armored fighting vehicle, the use of concentrated solar power, a ratio machine that could be used in an adding machine,[1] a rudimentary theory of plate tectonics and the double hull.[2] In practice, he greatly advanced the state of knowledge in the fields of anatomy, astronomy, civil engineering, optics, and the study of water (hydrodynamics).

One of Leonardo’s drawings, the Vitruvian Man, is a study of the proportions of the human body, linking art and science in a single work that has come to represent the concept of macrocosm and microcosm in Renaissance humanism.

Approach to scientific investigation[edit]

Investigating the motion of the arm.

During the Renaissance, the study of art and science was not perceived as mutually exclusive; on the contrary, the one was seen as informing upon the other. Although Leonardo’s training was primarily as an artist, it was largely through his scientific approach to the art of painting, and his development of a style that coupled his scientific knowledge with his unique ability to render what he saw that created the outstanding masterpieces of art for which he is famous.

As a scientist, Leonardo had no formal education in Latin and mathematics and did not attend a university. Because of these factors, his scientific studies were largely ignored by other scholars. Leonardo’s approach to science was one of intense observation and detailed recording, his tools of investigation being almost exclusively his eyes. His journals give insight into his investigative processes.

As a researcher, Leonardo divided nature and phenomena into ever smaller segments, concretely with knives and measuring instruments, intellectually with formulas and numbers, to wrest the secrets of creation from it. The smaller the particles, runs the assumption; the closer one will get to the solution of the enigmas.[3]

A recent and exhaustive analysis of Leonardo as a scientist by Fritjof Capra argues that Leonardo was a fundamentally different kind of scientist from Galileo, Newton, and other scientists who followed him, his theorizing and hypothesizing integrating the arts and particularly painting. Capra sees Leonardo’s unique integrated, holistic views of science as making him a forerunner of modern systems theory and complexity schools of thought.[4]

Leonardo’s notes and journals[edit]

Leonardo kept a series of journals in which he wrote almost daily, as well as separate notes and sheets of observations, comments and plans. He wrote and drew with his left hand, and most of his writing is in mirror script, which makes it difficult to read. Much has survived to illustrate Leonardo’s studies, discoveries and inventions.

On his death, the writings were left mainly to his pupil and heir Francesco Melzi, with the apparent intention that his scientific work should be published. Sometime before 1542, Melzi gathered together the papers for A Treatise on Painting from eighteen of Leonardo’s ‘books’ (two-thirds of which have gone missing).[5] The publishing did not take place in Melzi’s lifetime, and the writings were eventually bound in different forms and dispersed. Some of his works were published as A Treatise on Painting 165 years after his death.

Publication[edit]

Leonardo illustrated a book on mathematical proportion in art written by his friend Luca Pacioli and called De divina proportione, published in 1509. He was also preparing a major treatise on his scientific observations and mechanical inventions. It was to be divided into a number of sections or «Books», Leonardo leaving some instructions as to how they were to be ordered. Many sections of it appear in his notebooks.

These pages deal with scientific subjects generally but also specifically as they touch upon the creation of artworks. In relating to art, this is not science that is dependent upon experimentation or the testing of theories. It deals with detailed observation, particularly the observation of the natural world, and includes a great deal about the visual effects of light on different natural substances such as foliage.[6]

Leonardo wrote:

Begun at Florence, in the house of Piero di Braccio Martelli, on the 22nd day of March 1508. And this is to be a collection without order, taken from many papers which I have copied here, hoping to arrange them later each in its place, according to the subjects of which they may treat. But I believe that before I am at the end of this [task] I shall have to repeat the same things several times; for which, O reader! do not blame me, for the subjects are many and memory cannot retain them [all] and say: ‘I will not write this because I wrote it before.’ And if I wished to avoid falling into this fault, it would be necessary in every case when I wanted to copy [a passage] that, not to repeat myself, I should read over all that had gone before; and all the more since the intervals are long between one time of writing and the next.[6]

Natural science[edit]

Study of the graduations of light and shade on a sphere (chiaroscuro).

Light[edit]

Leonardo wrote:

The lights which may illuminate opaque bodies are of 4 kinds. These are; diffused light as that of the atmosphere; And Direct, as that of the sun; The third is Reflected light; and there is a 4th which is that which passes through [translucent] bodies, as linen or paper etc.[6]

For an artist working in the 15th century, some study of the nature of light was essential. It was by the effective painting of light falling on a surface that modelling, or a three-dimensional appearance was to be achieved in a two-dimensional medium. It was also well understood by artists like Leonardo’s teacher, Verrocchio, that an appearance of space and distance could be achieved in a background landscape by painting in tones that were less in contrast and colors that were less bright than in the foreground of the painting. The effects of light on solids were achieved by trial and error, since few artists except Piero della Francesca actually had accurate scientific knowledge of the subject.

At the time when Leonardo commenced painting, it was unusual for figures to be painted with extreme contrast of light and shade. Faces, in particular, were shadowed in a manner that was bland and maintained all the features and contours clearly visible. Leonardo broke with this.

In the painting generally titled The Lady with an Ermine (about 1483) he sets the figure diagonally to the picture space and turns her head so that her face is almost parallel to her nearer shoulder. The back of her head and the further shoulder are deeply shadowed. Around the ovoid solid of her head and across her breast and hand the light is diffused in such a way that the distance and position of the light in relation to the figure can be calculated.

Leonardo’s treatment of light in paintings such as The Virgin of the Rocks and the Mona Lisa was to change forever the way in which artists perceived light and used it in their paintings. Of all Leonardo’s scientific legacies, this is probably the one that had the most immediate and noticeable effect.

Human anatomy[edit]

Leonardo wrote:

…to obtain a true and perfect knowledge … I have dissected more than ten human bodies, destroying all the other members, and removing the very minutest particles of the flesh by which these veins are surrounded, … and as one single body would not last so long, since it was necessary to proceed with several bodies by degrees, until I came to an end and had a complete knowledge; this I repeated twice, to learn the differences…[6]

Study of the proportions of the head.

Topographic anatomy[edit]

Leonardo began the formal study of the topographical anatomy of the human body when apprenticed to Andrea del Verrocchio. As a student he would have been taught to draw the human body from life, to memorize the muscles, tendons and visible subcutaneous structure and to familiarise himself with the mechanics of the various parts of the skeletal and muscular structure. It was common workshop practice to have plaster casts of parts of the human anatomy available for students to study and draw.

If, as is thought to be the case, Leonardo painted the torso and arms of Christ in The Baptism of Christ on which he famously collaborated with his master Verrocchio, then his understanding of topographical anatomy had surpassed that of his master at an early age as can be seen by a comparison of the arms of Christ with those of John the Baptist in the same painting.

In the 1490s he wrote about demonstrating muscles and sinews to students:

Remember that to be certain of the point of origin of any muscle, you must pull the sinew from which the muscle springs in such a way as to see that muscle move, and where it is attached to the ligaments of the bones.[6]

His continued investigations in this field occupied many pages of notes, each dealing systematically with a particular aspect of anatomy. It appears that the notes were intended for publication, a task entrusted on his death to his pupil Melzi.

In conjunction with studies of aspects of the body are drawings of faces displaying different emotions and many drawings of people suffering facial deformity, either congenital or through illness. Some of these drawings, generally referred to as «caricatures», on analysis of the skeletal proportions, appear to be based on anatomical studies.

Dissection[edit]

As Leonardo became successful as an artist, he was given permission to dissect human corpses at the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. Later he dissected in Milan at the hospital Maggiore, and in Rome at the Ospedale di Santo Spirito (the first mainland Italian hospital). From 1510 to 1511 he collaborated in his studies with the doctor Marcantonio della Torre.

I have removed the skin from a man who was so shrunk by illness that the muscles were worn down and remained in a state like thin membrane, in such a way that the sinews instead of merging in muscles ended in wide membrane; and where the bones were covered by the skin they had very little over their natural size.[6]

In 30 years, Leonardo dissected 30 male and female corpses of different ages. Together with Marcantonio, he prepared to publish a theoretical work on anatomy and made more than 200 drawings. However, his book was published only in 1680 (161 years after his death) under the heading A Treatise on Painting.

The organs of a woman’s body

Among the detailed images that Leonardo drew are many studies of the human skeleton. He was the first to describe the double S form of the backbone. He also studied the inclination of pelvis and sacrum and stressed that sacrum was not uniform, but composed of five fused vertebrae. He also studied the anatomy of the human foot and its connection to the leg, and from these studies, he was able to further his studies in biomechanics.

Leonardo was a physiologist as well as an anatomist, studying the function of the human body as well as examining and recording its structure. He dissected and drew the human skull and cross-sections of the brain, transversal, sagittal, and frontal. These drawings may be linked to a search for the sensus communis, the locus of the human senses,[citation needed] which, by Medieval tradition, was located at the exact physical center of the skull.

Studies of a fœtus from Leonardo’s journals

Leonardo studied internal organs, being the first to draw the human appendix and the lungs, mesentery, urinary tract, reproductive organs, the muscles of the cervix and a detailed cross-section of coitus. He was one of the first to draw a scientific representation of the fetus in the intrautero.

Leonardo studied the vascular system and drew a dissected heart in detail. He correctly worked out how heart valves ebb the flow of blood yet he did not fully understand circulation, as he believed that blood was pumped to the muscles where it was consumed. In 2005 a UK heart surgeon, Francis Wells, from Papworth Hospital Cambridge, pioneered repair to damaged hearts, using Leonardo’s depiction of the opening phase of the mitral valve to operate without changing its diameter allowing an individual to recover more quickly. Wells said «Leonardo had a depth of appreciation of the anatomy and physiology of the body – its structure and function – that perhaps has been overlooked by some.»[7]

Leonardo’s observational acumen, drawing skill, and the clarity of depiction of bone structures reveal him at his finest as an anatomist. However, his depiction of the internal soft tissues of the body are incorrect in many ways, showing that he maintained concepts of anatomy and functioning that were in some cases millennia old, and that his investigations were probably hampered by the lack of preservation techniques available at the time. Leonardo’s detailed drawing of the internal organs of a woman (See left) reveal many traditional misconceptions.[8][9]

Leonardo’s study of human anatomy led also to the design of an automaton which has come to be called Leonardo’s robot, was probably made around the year 1495 but was rediscovered only in the 1950s.

Comparative anatomy[edit]

Comparison of the leg of a man and a dog.

Leonardo not only studied human anatomy, but the anatomy of many other animals as well. He dissected cows, birds, monkeys and frogs, comparing in his drawings their anatomical structure with that of humans. On one page of his journal Leonardo drew five profile studies of a horse with its teeth bared in anger and, for comparison, a snarling lion and a snarling man.

I have found that in the composition of the human body as compared with the bodies of animals, the organs of sense are duller and coarser… I have seen in the Lion tribe that the sense of smell is connected with part of the substance of the brain which comes down the nostrils, which form a spacious receptacle for the sense of smell, which enters by a great number of cartilaginous vesicles with several passages leading up to where the brain, as before said, comes down.[6]

In the early 1490s Leonardo was commissioned to create a monument in honour of Francesco Sforza. In his notebooks are a series of plans for an equestrian monument. There are also a large number of related anatomical studies of horses. They include several diagrams of a standing horse with the angles and proportions annotated, anatomical studies of horses’ heads, a dozen detailed drawings of hooves and numerous studies and sketches of horses rearing.

He studied the topographical anatomy of a bear in detail, making many drawings of its paws. There is also a drawing of the muscles and tendons of the bear’s hind feet.

Other drawings of particular interest include the uterus of a pregnant cow, the hindquarters of a decrepit mule and studies of the musculature of a little dog.

Botany[edit]

The science of botany was long established by Leonardo’s time, a treatise on the subject having been written as early as 300 BCE.[10] Leonardo’s study of plants, resulting in many detailed drawings in his notebooks, was not to record in diagrammatic form the parts of the plant, but rather, as an artist and observer to record the precise appearance of plants, the manner of growth and the way that individual plants and flowers of a single variety differed from one another.

One such study shows a page with several species of flower of which ten drawings are of wild violets. Along with a drawing of the growing plant and a detail of a leaf, Leonardo has repeatedly drawn single flowers from different angles, with their heads set differently on the stem.

Apart from flowers the notebooks contain many drawings of crop plants including several types of grain and a variety of berries including a detailed study of bramble. There are also water plants such as irises and sedge. His notebooks also direct the artist to observe how light reflects from foliage at different distances and under different atmospheric conditions.

A number of the drawings have their equivalents in Leonardo’s paintings. An elegant study of a stem of lilies may have been for one of Leonardo’s early Annunciation paintings, carried in the hand of the Archangel Gabriel. In both the Annunciation pictures the grass is dotted with blossoming plants.

The plants which appear in the Louvre version of The Virgin of the Rocks reflects the results of Leonardo’s studies in a meticulous realism that makes each plant readily identifiable to the botanist.

In A Treatise on Painting, Leonardo proposed the following branching rule:

All the branches of a tree at every stage of its height when put together are equal in thickness to the trunk [below them].[6]

Geology[edit]

As an adult, Leonardo had only two childhood memories, one of which was the finding of a cave in the Apennines. Although fearing that he might be attacked by a wild beast, he ventured in driven «by the burning desire to see whether there might be any marvelous thing within.»

Leonardo’s earliest dated drawing is a study of the Arno valley, strongly emphasizing its geological features. His notebooks contain landscapes with a wealth of geological observation from the regions of both Florence and Milan, often including atmospheric effects such as a heavy rainstorm pouring down on a town at the foot of a mountain range.

It had been observed for many years that strata in mountains often contained bands of sea shells. Conservative science said that these could be explained by the Great Flood described in the Bible. Leonardo’s observations convinced him that this could not possibly be the case.

And a little beyond the sandstone conglomerate, a tufa has been formed, where it turned towards Castel Florentino; farther on, the mud was deposited in which the shells lived, and which rose in layers according to the levels at which the turbid Arno flowed into that sea. And from time to time the bottom of the sea was raised, depositing these shells in layers, as may be seen in the cutting at Colle Gonzoli, laid open by the Arno which is wearing away the base of it; in which cutting the said layers of shells are very plainly to be seen in clay of a bluish colour, and various marine objects are found there.[6]

This quotation makes clear the breadth of Leonardo’s understanding of geology, including the action of water in creating sedimentary rock, the tectonic action of the Earth in raising the sea bed and the action of erosion in the creation of geographical features.

In Leonardo’s earliest paintings we see the remarkable attention given to the small landscapes of the background, with lakes and water, swathed in a misty light. In the larger of the Annunciation paintings is a town on the edge of a lake. Although distant, the mountains can be seen to be scored by vertical strata. This characteristic can be observed in other paintings by Leonardo, and closely resembles the mountains around Lago di Garda and Lago d’Iseo in Northern Italy. It is a particular feature of both the paintings of The Virgin of the Rocks, which also include caverns of fractured, tumbled, and water-eroded limestone.[11]

Cartography[edit]

Leonardo’s accurate map of Imola for Cesare Borgia.

In the early 16th century maps were rare and often inaccurate. Leonardo produced several extremely accurate maps such as the town plan of Imola created in 1502 in order to win the patronage of Cesare Borgia. Borgia was so impressed that he hired him as a military engineer and architect. Leonardo also produced a map of Chiana Valley in Tuscany, which he surveyed, without the benefit of modern equipment, by pacing the distances. In 1515, Leonardo produced a map of the Roman Southern Coast which is linked to his work for the Vatican and relates to his plans to drain the marshland.

Recent research by Donato Pezzutto suggests that the background landscapes in Leonardo’s paintings depict specific locations as aerial views with enhanced depth, employing a technique called cartographic perspective. Pezzutto identifies the location of the Mona Lisa to the Val di Chiana, the Annunciation to the Arno Valley, the Madonna of the Yarnwinder to the Adda Valley and The Virgin and Child with St Anne to the Sessia Valley.[12]

Hydrodynamics[edit]

Leonardo wrote:

All the branches of a water [course] at every stage of its course, if they are of equal rapidity, are equal to the body of the main stream.[6]

Among Leonardo’s drawings are many that are studies of the motion of water, in particular the forms taken by fast-flowing water on striking different surfaces.

Many of these drawings depict the spiralling nature of water. The spiral form had been studied in the art of the Classical era and strict mathematical proportion had been applied to its use in art and architecture. An awareness of these rules of proportion had been revived in the early Renaissance. In Leonardo’s drawings can be seen the investigation of the spiral as it occurs in water.

There are several elaborate drawings of water curling over an object placed at a diagonal to its course. There are several drawings of water dropping from a height and curling upwards in spiral forms. One such drawing, as well as curling waves, shows splashes and details of spray and bubbles.

Leonardo’s interest manifested itself in the drawing of streams and rivers, the action of water in eroding rocks, and the cataclysmic action of water in floods and tidal waves. The knowledge that he gained from his studies was employed in devising a range of projects, particularly in relation to the Arno River. None of the major works was brought to completion.

Astronomy[edit]

Leonardo lived at a time when geocentric theories were the most widely used explanations to account for the relationship between the Earth and Sun’s movement. He wrote that «The Sun has substance, shape, movement, radiance, heat, and generative power; and these qualities all emanate from itself without its diminution.»[13] He further wrote,

The earth is not in the centre of the Sun’s orbit nor at the centre of the universe, but in the centre of its companion elements, and united with them. And any one standing on the moon, when it and the sun are both beneath us, would see this our earth and the element of water upon it just as we see the moon, and the earth would light it as it lights us.[14]

In one of his notebooks, there is a note in the margin which states, «The Sun does not move,» which may indicate Leonardo’s support of heliocentrism.[15]

Alchemy[edit]

Claims are sometimes made that Leonardo da Vinci was an alchemist. He was trained in the workshop of Verrocchio, who according to Vasari, was an able alchemist. Leonardo was a chemist in so much as that he experimented with different media for suspending paint pigment. In the painting of murals, his experiments resulted in notorious failures with The Last Supper deteriorating within a century, and The Battle of Anghiari running off the wall. In Leonardo’s many pages of notes about artistic processes, there are some that pertain to the use of silver and gold in artworks, information he would have learned as a student.[16]

Leonardo’s scientific process was based mainly upon observation. His practical experiments are also founded in observation rather than belief. Leonardo, who questioned the order of the Solar System and the deposit of fossils by the Great Flood, had little time for the alchemical quests to turn lead into gold or create a potion that gave eternal life.

Leonardo said about alchemists:

The false interpreters of nature declare that quicksilver is the common seed of every metal, not remembering that nature varies the seed according to the variety of the things she desires to produce in the world.[6][17]

Old alchemists… have never either by chance or by experiment succeeded in creating the smallest element that can be created by nature; however [they] deserve unmeasured praise for the usefulness of things invented for the use of men, and would deserve it even more if they had not been the inventors of noxious things like poisons and other similar things which destroy life or mind.[18]

And many have made a trade of delusions and false miracles, deceiving the stupid multitude.[6]

Mathematical studies[edit]

Perspective[edit]

The art of perspective is of such a nature as to make what is flat appear in relief and what is in relief flat.[6]

During the early 15th century, both Brunelleschi and Alberti made studies of linear perspective. In 1436 Alberti published De pictura («On Painting»), which includes his findings on linear perspective. Piero della Francesca carried his work forward and by the 1470s a number of artists were able to produce works of art that demonstrated a full understanding of the principles of linear perspective.

Leonardo studied linear perspective and employed it in his earlier paintings. His use of perspective in the two Annunciations is daring, as he uses various features such as the corner of a building, a walled garden and a path to contrast enclosure and spaciousness.

The unfinished Adoration of the Magi was intended to be a masterpiece revealing much of Leonardo’s knowledge of figure drawing and perspective. There exists a number of studies that he made, including a detailed study of the perspective, showing the complex background of ruined Classical buildings that he planned for the left of the picture. In addition, Leonardo is credited with the first use of anamorphosis, the use of a «perspective» to produce an image that is intelligible only with a curved mirror or from a specific vantage point.[19]

Leonardo wrote:

Those who are in love with practice without knowledge are like the sailor who gets into a ship without rudder or compass and who never can be certain whither he is going. Practice must always be founded on sound theory, and to this Perspective is the guide and the gateway; and without this nothing can be done well in the matter of drawing.[6][20]

Geometry[edit]

While in Milan in 1496, Leonardo met a traveling monk and academic, Luca Pacioli. Under him, Leonardo studied mathematics. Pacioli, who first codified and recorded the double entry system of bookkeeping,[21] had already published a major treatise on mathematical knowledge, collaborated with Leonardo in the production of a book called De divina proportione about mathematical and artistic proportion. Leonardo prepared a series of drawings of regular solids in a skeletal form to be engraved as plates. De divina proportione was published in 1509.

All the problems of perspective are made clear by the five terms of mathematicians, which are:—the point, the line, the angle, the superficies and the solid. The point is unique of its kind. And the point has neither height, breadth, length, nor depth, whence it is to be regarded as indivisible and as having no dimensions in space.[6]

Engineering and invention[edit]

Vasari in The Lives says of Leonardo:

He made designs for mills, fulling machines and engines that could be driven by water-power… In addition he used to make models and plans showing how to excavate and tunnel through mountains without difficulty, so as to pass from one level to another; and he demonstrated how to lift and draw great weights by means of levers, hoists and winches, and ways of cleansing harbours and using pumps to suck up water from great depths.

Practical inventions and projects[edit]

A machine for grinding convex lenses

With the same rational and analytical approach that he used in anatomic studies, Leonardo faced the study and design of a bewildering number of machines and devices. He drew their «anatomy» with unparalleled mastery, producing the first form of the modern technical drawing, include a perfected «exploded view» technique, to represent internal components. Those studies and projects have been collected in his codices and fill more than 5,000 pages.[22] Leonardo was a master of mechanical principles. He utilized leverage and cantilevering, pulleys, cranks, gears, including angle gears and rack and pinion gears; parallel linkage, lubrication systems and bearings. He understood the principles governing momentum, centripetal force, friction and the aerofoil and applied these to his inventions. His scientific studies remained unpublished with, for example, his manuscripts describing the processes governing friction predating the introduction of Amontons’ laws of friction by 150 years.[23]

It is impossible to say with any certainty how many or even which of his inventions passed into general and practical use, and thereby had impact over the lives of many people. Among those inventions that are credited with passing into general practical use are the strut bridge, the automated bobbin winder, the rolling mill, the machine for testing the tensile strength of wire and the lens-grinding machine pictured at right. In the lens-grinding machine, the hand rotation of the grinding wheel operates an angle-gear, which rotates a shaft, turning a geared dish in which sits the glass or crystal to be ground. A single action rotates both surfaces at a fixed speed ratio determined by the gear.

As an inventor, Leonardo was not prepared to tell all that he knew:

How by means of a certain machine many people may stay some time under water. How and why I do not describe my method of remaining under water, or how long I can stay without eating; and I do not publish nor divulge these by reason of the evil nature of men who would use them as means of destruction at the bottom of the sea, by sending ships to the bottom, and sinking them together with the men in them. And although I will impart others, there is no danger in them; because the mouth of the tube, by which you breathe, is above the water supported on bags of corks.[6]

Bridges and hydraulics[edit]

Various hydraulic machines

Leonardo’s study of the motion of water led him to design machinery that utilized its force. Much of his work on hydraulics was for Ludovico il Moro. Leonardo wrote to Ludovico describing his skills and what he could build:

…very light and strong bridges that can easily be carried, with which to pursue, and sometimes flee from, the enemy; and others safe and indestructible by fire or assault, easy and convenient to transport and place into position.

Among his projects in Florence was one to divert the course of the Arno, in order to flood Pisa. Fortunately, this was too costly to be carried out. He also surveyed Venice and came up with a plan to create a movable dyke for the city’s protection against invaders.

In 1502, Leonardo produced a drawing of a single span 240 m (720 ft) bridge as part of a civil engineering project for Ottoman Sultan Beyazid II of Istanbul. The bridge was intended to span an inlet at the mouth of the Bosphorus known as the Golden Horn. Beyazid did not pursue the project, because he believed that such a construction was impossible. Leonardo’s vision was resurrected in 2001 when a smaller bridge based on his design was constructed in Norway.

A stone model of the bridge was evaluated in 2019 by MIT researchers. The self-supporting 1:500 scale model was built from 126 3D-printed stone cross-sections, held together without mortar. Researchers concluded that the bridge would’ve been able to support its own weight, and maintain stability under load and wind shear forces.[24]

War machines[edit]

Leonardo’s letter to Ludovico il Moro assured him:

When a place is besieged I know how to cut off water from the trenches and construct an infinite variety of bridges, mantlets and scaling ladders, and other instruments pertaining to sieges. I also have types of mortars that are very convenient and easy to transport…. when a place cannot be reduced by the method of bombardment either because of its height or its location, I have methods for destroying any fortress or other stronghold, even if it be founded upon rock. ….If the engagement be at sea, I have many engines of a kind most efficient for offence and defence, and ships that can resist cannons and powder.

In Leonardo’s notebooks there is an array of war machines which includes a vehicle to be propelled by two men powering crank shafts. Although the drawing itself looks quite finished, the mechanics were apparently not fully developed because, if built as drawn, the vehicle would never progress in a forward direction. In a BBC documentary, a military team built the machine and changed the gears in order to make the machine work. It has been suggested that Leonardo deliberately left this error in the design, in order to prevent it from being put to practice by unauthorized people.[25] Another machine, propelled by horses with a pillion rider, carries in front of it four scythes mounted on a revolving gear, turned by a shaft driven by the wheels of a cart behind the horses.

Leonardo’s proposed vehicle

Leonardo’s notebooks also show cannons which he claimed «to hurl small stones like a storm with the smoke of these causing great terror to the enemy, and great loss and confusion.» He also designed an enormous crossbow. Following his detailed drawing, one was constructed by the British Army, but could not be made to fire successfully. In 1481 Leonardo designed a breech-loading, water cooled cannon with three racks of barrels allowed the re-loading of one rack while another was being fired and thus maintaining continuous fire power. The «fan type» gun with its array of horizontal barrels allowed for a wide scattering of shot.

Leonardo was the first to sketch the wheel-lock musket c. 1500 AD (the precedent of the flintlock musket which first appeared in Europe by 1547), although as early as the 14th century the Chinese had used a flintlock ‘steel wheel’ in order to detonate land mines.[26]

While Leonardo was working in Venice, he drew a sketch for an early diving suit, to be used in the destruction of enemy ships entering Venetian waters. A suit was constructed for a BBC documentary using pigskin treated with fish oil to repel water. The head was covered by a helmet with two eyeglasses at the front. A breathing tube of bamboo with pigskin joints was attached to the back of the helmet and connected to a float of cork and wood. When the scuba divers tested the suit, they found it to be a workable precursor to a modern diving suit, the cork float acting as a compressed air chamber when submerged.[27]

His inventions were very futuristic which meant they were very expensive and proved not to be useful.

Flight[edit]

In Leonardo’s infancy a hawk had once hovered over his cradle. Recalling this incident, Leonardo saw it as prophetic:

An object offers as much resistance to the air as the air does to the object. You may see that the beating of its wings against the air supports a heavy eagle in the highest and rarest atmosphere, close to the sphere of elemental fire. Again you may see the air in motion over the sea, fill the swelling sails and drive heavily laden ships. From these instances, and the reasons given, a man with wings large enough and duly connected might learn to overcome the resistance of the air, and by conquering it, succeed in subjugating it and rising above it.[6]

Design for a flying machine with wings based closely upon the structure of a bat’s wings.

The desire to fly is expressed in the many studies and drawings. His later journals contain a detailed study of the flight of birds and several different designs for wings based in structure upon those of bats which he described as being less heavy because of the impenetrable nature of the membrane. There is a legend that Leonardo tested the flying machine on Monte Ceceri with one of his apprentices, and that the apprentice fell and broke his leg.[28] Experts Martin Kemp and Liana Bortolon agree that there is no evidence of such a test, which is not mentioned in his journals.

One design that he produced shows a flying machine to be lifted by a man-powered rotor.[29] It would not have worked since the body of the craft itself would have rotated in the opposite direction to the rotor.[30]

While he designed a number of man powered flying machines with mechanical wings that flapped, he also designed a parachute and a light hang glider which could have flown.[31]

Musical instrument[edit]

The viola organista was an experimental musical instrument invented by Leonardo da Vinci. It was the first bowed keyboard instrument (of which any record has survived) ever to be devised.

Leonardo’s original idea, as preserved in his notebooks of 1488–1489 and in the drawings in the Codex Atlanticus, was to use one or more wheels, continuously rotating, each of which pulled a looping bow, rather like a fanbelt in an automobile engine, and perpendicular to the instrument’s strings.

Leonardo’s inventions made reality[edit]

In the late 20th century, interest in Leonardo’s inventions escalated. There have been many projects which have sought to turn diagrams on paper into working models. One of the factors is the awareness that, although in the 15th and 16th centuries Leonardo had available a limited range of materials, modern technological advancements have made available a number of robust materials of light-weight which might turn Leonardo’s designs into reality. This is particularly the case with his designs for flying machines.

A difficulty encountered in the creation of models is that often Leonardo had not entirely thought through the mechanics of a machine before he drew it, or else he used a sort of graphic shorthand, simply not bothering to draw a gear or a lever at a point where one is essential in order to make a machine function. This lack of refinement of mechanical details can cause considerable confusion. Thus, many models that are created, such as some of those on display at Clos Lucé, Leonardo’s home in France, do not work, but would work, with a little mechanical tweaking.

Accidental perspective and anamorphosis[edit]

Anamorphosis[edit]

…And if you will paint this on a wall in front of which you can move freely, it will look out of proportion… and if notwithstanding that you still wish to paint it, it will be necessary that your perspective is seen through a single hole…

Leonardo was the author of some of the earliest known examples of pictorial anamorphosis identified and studied.[32][33]

Anamorphosis is a type of optical artifice in which images are represented with altered proportions, and are recognizable only when the image is observed from a specific vantage point or using distorting instruments. A notable example in painting is The Ambassadors (1533) by Hans Holbein the Younger.

Leonardo da Vinci: Tool for the angle of contingency reconstructed from the Codex Atlanticus

Instruments[edit]

One of the instruments used by Leonardo for his research on anamorphosis was the tool for the angle of contingence, recreated in modern times using the Codex Atlanticus.[34] It is an instrument to determine the reflexion angle of a ray of light incident on the surface of a cylindrical mirror.

First examples[edit]

The first examples of Leonardo’s studies on anamorphosis can be found both in his treatise Treatise on Painting («Rules for the Painter»)[35] and in the Codex Atlanticus.[34] Two anamorphic drawings of the Codex Atlanticus, representing the head of a baby and an eye, are examples of plane anamorphosis.[36][37]

Two anamorphic drawings, a face of a baby and an eye in Codex Atlanticus folio 98 recto.

The two drawings can be adjusted when observed from a foreshortening angle, placing the eye on the right side of the sheet, about middle height. The original paper displays a preparation with a bundle of lines traced with a metal tip inside which the figures are inscripted; these lines are invisible in any reproduction.[38][39][40] A chapter in the Codex Arundel 263 (c.62, 9r.) with the title «On natural perspective mixed with accidental perspective» explains how to apply an accidental viewpoint to that of a natural surface, in order for the moving observer to obtain the vision of a «monstrous» figure. This was the procedure used to accomplish the «Fight Between a Dragon and a Lion» and Painting with Horses, so peculiar as to attract the attention of Francis I of France demonstrating the presence of a geometric construction underlying the sketches, which can be seen in their real proportions only observing them with the usual technique needed for ‘anamorphic’ paintings.

According to Jurgis Baltrušaitis these are some of the oldest examples of anamorphosis known at the time, and with reference to the technique he stated:

…undoubtedly at first the recipes were kept closely secret, the exact geometric procedures were integrally revealed only during the XVII century, with the creation of the second group of anamorphoses and its spreading in multiple directions…[38]

Other studies on this topic were later reinforced and widened by Panofsky (1940) and White (1957).[41]

The Codex A[42] of the Institut de France includes the description of a technique to build an anamorphosis using a hole through which letting a ray of light project the shadow of what is to be drawn on a dedicated wall. This drawing technique is defined by Leonardo as «accidental perspective», in which farther objects needed to be drawn bigger than close ones, in contrast with what is observed in reality («natural perspective»).

Anamorphic virtuosities[edit]

In the Uffizi Annunciation, sparsely documented early work by Leonardo once wrongly attributed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, the shortcomings, mistakes, including a seemingly gross perspective one and the subsequent doubts concerning its authorship, were caused by the failure to understand the principles of anamorphosis. Mary in the painting is represented reading in the garden, when she is surprised by the arrival of Archangel Gabriel, the Virgin looks almost gloomy, while her right hand chastely appears to hold back the annunciation of the divine messenger. In Leonardo’s composition, the bookstand on which the Virgin lays her right hand, constrains her in an unusual position. Observing the painting from a central point of view, when looked at frontally, the limb appears too long and unjointed, almost unnatural. But thanks to the remarks of Carlo Pedretti’s[43] (one of the greatest experts on Leonardo) and Antonio Natali’s,[44] (Director of the Uffizi), it is now understood that when observed from a vantage point, not only does the arm appear perfectly proportioned, but the figure of Archangel Gabriel, who would have looked too off-balance from ahead, regains a more natural pose.[45][46] The erroneous attempt to blame this seeming imperfection to the young author’s inexperience is overcome by the clear use of an anamorphic composition of the painting by Leonardo, following the example of other great artists of the early Renaissance, such as Florentine artists Donatello and Filippo Lippi.

The errors of perspective can be summarized as follows: the Virgin’s right arm being longer than the left one, too short legs compared to the height of the torso, the cypress confused with the fifteenth-century building, making it appear bigger, the different placing of the Virgin’s legs and shoulders relative to the bookstand. The error of perspective is the result of the will of the painter, and arises from the need to accommodate the placing of the painting on a wall that would have been looked at mainly in foresight from the right; it is actually observing the Annunciation from a right sided lateral position that the disproportion of the arm subsides, as an effect of the anamorphosis.

Leonardo’s projects[edit]

-

Walking on water

-

A parabolic compass

-

A water powered gyroscopic compass

-

Cannons (Firing)

-

Sketch of a lifebelt

Models based on Leonardo’s drawings[edit]

-

Model of a Leonardo bridge

-

Model of Leonardo’s parachute

-

Model after Leonardo’s design for the Golden Horn Bridge

-

Model of a fighting vehicle by Leonardo

-

Model of a flywheel

Exhibitions[edit]

- Leonardo da Vinci Gallery at Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci in Milan; permanent exhibition, the biggest collection of Leonardo’s projects and inventions.[47]

- Models of Leonardo’s designs are on permanent display at Clos Lucé.

- The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, held an exhibition called «Leonardo da Vinci: Experience, Experiment, and Design» in 2006

- Logitech Museum

- «The Da Vinci Machines Exhibition» was held in a pavilion in the Cultural Forecourt, at South Bank, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia in 2009. The exhibits shown were on loan from the Museum of Leonardo da Vinci, Florence, Italy.

Television programs[edit]

- The U.S. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), aired in October 2005, a television programme called Leonardo’s Dream Machines, about the building and successful flight of a glider based upon Leonardo’s design.

- The Discovery Channel began a series called Doing DaVinci in April 2009, in which a team of builders try to construct various inventions of Leonardo based on his designs.[48]

See also[edit]

- List of works by Leonardo da Vinci

- Ostrich Egg Globe

- Personal life of Leonardo da Vinci

Notes[edit]

- ^ Kaplan, E. (Apr 1997). «Anecdotes». IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 19 (2): 62–69. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1997.586074. ISSN 1058-6180.

- ^ Innocenzi, Plinio (2018). The innovators behind Leonardo: The True Story of the Scientific and Technological Renaissance. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 9783319904481.

- ^ Marc van den Broek (2019), Leonardo da Vinci Spirits of Invention. A Search for Traces, Hamburg: A.TE.M., ISBN 978-3-00-063700-1

- ^ Capra, Fritjof. The Science of Leonardo; Inside the Mind of the Genius of the Renaissance. (New York, Doubleday, 2007)

- ^ Wallace 1972, p. 170.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Jean Paul Richter editor 1880, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci Dover, 1970, ISBN 0-486-22572-0. (accessed 2007-02-04)

- ^ «Da Vinci clue for heart surgeon». BBC News. 2005-09-28. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ Martin Kemp, Leonardo, Oxford University Press, (2004) ISBN 0-19-280644-0

- ^ Live Science

- ^ E.g. Theophrastus, On the History of Plants.

- ^ The London painting of the Virgin of the Rocks is denounced by the geologist Ann C. Pizzorusso, [1] of New York, as largely by the hand of someone other than Leonardo, because the rocks appear incongruous and the lake looks like a fjord. Pizzorusso says «Fjords do not exist in Italy and it is highly unlikely the glacial lakes of the Lombard region would have such steep relief surrounding them.» In fact, the glacial lake, Garda, has just such steep geological formations. The sedimentary red limestone which appears in the picture is also typical of Italy.

- ^ Pezzutto, Donato (2012-10-24). «Leonardo’s Landscapes as Maps». OPUSeJ. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- ^ Livio, Dr. Mario (8 October 2013). «The Da Vinci Astronomy». Huff Post. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Da Vinci’s notebooks on astronomy.

- ^ «Leonardo Da Vinci». Giants of Science. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Bruce T. Moran, Distilling Knowledge, Chemistry, Alchemy and the Scientific Revolution, (2005) ISBN 0-674-01495-2

- ^ «Quicksilver» is an old name for mercury.

- ^ Irma Ann Richter and Teresa Wells, Leonardo da Vinci – Notebooks, Oxford University Press (2008) ISBN 978-0-19-929902-7

- ^ «Animations of anamorphosis of Leonardo and other artists». Illusionworks.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-13. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ «Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson». Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ^ L. Murphy Smith, Luca Pacioli: The Father of Accounting Archived 2011-08-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Guarnieri, M. (2019). «Reconsidering Leonardo». IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine. 13 (3): 35–38. doi:10.1109/MIE.2019.2929366. hdl:11577/3310853. S2CID 202729396.

- ^ «Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)». Nano-world.org. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

- ^ Chandler, David L. (2019-10-09). «Engineers put Leonardo da Vinci’s bridge design to the test». MIT News. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- ^ «Da Vinci war machines «designed to fail»«. The Age. Melbourne. December 14, 2002.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 199.

- ^ «Youtube Video of the BBC documentary». Archived from the original on 2010-10-13.

- ^ Liana Bortolon, Leonardo, Paul Hamlyn, (1967)

- ^ «The Helicopter » Leonardo Da Vinci’s Inventions». leonardodavincisinventions.com. Retrieved 2016-03-21.

- ^ see Helicopter for detailed description of solutions and types of functional helicopter.

- ^ U.S. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), Leonardo’s Dream Machine, October 2005

- ^ Bassoli, F., Leonardo da Vinci e l’invenzione delle anamorfosi, in «Atti della società dei Naturalisti e Matematici in Modena» LXIX/1938

- ^ Decio Gioseffi, Perspectiva artificialis: per la storia della prospettiva. Spigolature e appunti, Smolars, Trieste, 1957

- ^ a b Pedretti, Carlo (1978). The Codex Atlanticus of Leonardo Da Vinci. San Diego, California: Harcourt. ISBN 978-3840950032.

- ^ A Treatise on Painting, by Leonardo da Vinci 1721 Senex and Taylor, London

- ^ Leonardo Da Vinci, Codex Atlanticus, folio 98 recto-Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, dating around 1515

- ^ ««Eyed Awry»: Blind Spots and Memoria in the Zimmern Anamorphosis».

- ^ a b Baltrušaitis, Jurgis (1976) «Anamorphic Art». Trans. W.J. Strachn. Harry N. Abrams Inc. New York. Standard Book Number: 8109-0662-7. Library of Congress: 77-73789 ISBN 978-0810906624

- ^ J. Baltrusaitis, Anamorfosi o thaumaturgus opticus, Milano 2004

- ^ http://www.educational.rai.it/materiali/file_lezioni/64888_636314928342978742.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ White, John. The Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space, London : Faber and Faber, 1957.

- ^ C. Pedretti; M. Cianchi (April 1995). «Manoscritto A». Leonardo. I codici. p. 20.

- ^ Pedretti, Carlo (2006). Leonardo da Vinci. Surrey: Taj Books International. ISBN 978-1-8440-6036-8.Pedretti, Carlo (1982). Leonardo, a study in chronology and style. Cambridge: Johnson Reprint Corp. ISBN 978-0-3844-5281-7.

- ^ Antonio Natali, La montagna sul mare. L’Annunciazione di Leonardo (2006)

- ^ «Annunciazione | Opere | le Gallerie degli Uffizi».

- ^ «Il mistero dell’Annunciazione di Leonardo, Errori o Virtuosismi».

- ^ «Leonardo». Museoscienzaorg. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ About Doing DaVinci : Doing DaVinci : Discovery Channel Archived April 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

References[edit]

- Bsmbach, Carmen (2003). Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 414. ISBN 0-300-09878-2.

- Wallace, Robert (1972) [1966]. The World of Leonardo: 1452–1519. New York: Time-Life Books.

Further reading[edit]

- Moon, Francis C. (2007). The Machines of Leonardo da Vinci and Franz Reuleaux, Kinematics of Machines from the Renaissance to the 20th Century. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-5598-0.

- Capra, Fritjof (2007). The Science of Leonardo; Inside the Mind of the Genius of the Renaissance. New York: Doubleday.

External links[edit]

- The Art of War: Leonardo da Vinci’s War Machines

- Complete text & images of Richter’s translation of the Notebooks

- Leonardo da Vinci: Experience, Experiment, Design (review)

- Some digitized notebook pages with explanations from the British Library (Non HTML5 Available)

- Digital and animated compendium of anatomy notebook pages

- BBC Leonardo homepage

- Leonardo da Vinci: The Leicester Codex

- Leonardo’s Letter to Ludovico Sforza

- Animations of anamorphosis of Leonardo and other artists

- Da Vinci – The Genius: A comprehensive traveling exhibition about Leonardo da Vinci

- The technical drawings of Leonardo da Vinci – a high resolution gallery

- Leonardo da Vinci: anatomical drawings from the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, exhibition catalog fully online as PDF from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman, exhibition catalog fully online as PDF from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, Friday, 4 May 2012 to Sunday, 7 October 2012. High-resolution anatomical drawings.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was an Italian polymath, regarded as the epitome of the «Renaissance Man», displaying skills in numerous diverse areas of study. Whilst most famous for his paintings such as the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper, Leonardo is also renowned in the fields of civil engineering, chemistry, geology, geometry, hydrodynamics, mathematics, mechanical engineering, optics, physics, pyrotechnics, and zoology.

While the full extent of his scientific studies has only become recognized in the last 150 years, during his lifetime he was employed for his engineering and skill of invention. Many of his designs, such as the movable dikes to protect Venice from invasion, proved too costly or impractical. Some of his smaller inventions entered the world of manufacturing unheralded. As an engineer, Leonardo conceived ideas vastly ahead of his own time, conceptually inventing the parachute, the helicopter, an armored fighting vehicle, the use of concentrated solar power, a ratio machine that could be used in an adding machine,[1] a rudimentary theory of plate tectonics and the double hull.[2] In practice, he greatly advanced the state of knowledge in the fields of anatomy, astronomy, civil engineering, optics, and the study of water (hydrodynamics).

One of Leonardo’s drawings, the Vitruvian Man, is a study of the proportions of the human body, linking art and science in a single work that has come to represent the concept of macrocosm and microcosm in Renaissance humanism.

Approach to scientific investigation[edit]

Investigating the motion of the arm.

During the Renaissance, the study of art and science was not perceived as mutually exclusive; on the contrary, the one was seen as informing upon the other. Although Leonardo’s training was primarily as an artist, it was largely through his scientific approach to the art of painting, and his development of a style that coupled his scientific knowledge with his unique ability to render what he saw that created the outstanding masterpieces of art for which he is famous.

As a scientist, Leonardo had no formal education in Latin and mathematics and did not attend a university. Because of these factors, his scientific studies were largely ignored by other scholars. Leonardo’s approach to science was one of intense observation and detailed recording, his tools of investigation being almost exclusively his eyes. His journals give insight into his investigative processes.

As a researcher, Leonardo divided nature and phenomena into ever smaller segments, concretely with knives and measuring instruments, intellectually with formulas and numbers, to wrest the secrets of creation from it. The smaller the particles, runs the assumption; the closer one will get to the solution of the enigmas.[3]

A recent and exhaustive analysis of Leonardo as a scientist by Fritjof Capra argues that Leonardo was a fundamentally different kind of scientist from Galileo, Newton, and other scientists who followed him, his theorizing and hypothesizing integrating the arts and particularly painting. Capra sees Leonardo’s unique integrated, holistic views of science as making him a forerunner of modern systems theory and complexity schools of thought.[4]

Leonardo’s notes and journals[edit]

Leonardo kept a series of journals in which he wrote almost daily, as well as separate notes and sheets of observations, comments and plans. He wrote and drew with his left hand, and most of his writing is in mirror script, which makes it difficult to read. Much has survived to illustrate Leonardo’s studies, discoveries and inventions.

On his death, the writings were left mainly to his pupil and heir Francesco Melzi, with the apparent intention that his scientific work should be published. Sometime before 1542, Melzi gathered together the papers for A Treatise on Painting from eighteen of Leonardo’s ‘books’ (two-thirds of which have gone missing).[5] The publishing did not take place in Melzi’s lifetime, and the writings were eventually bound in different forms and dispersed. Some of his works were published as A Treatise on Painting 165 years after his death.

Publication[edit]

Leonardo illustrated a book on mathematical proportion in art written by his friend Luca Pacioli and called De divina proportione, published in 1509. He was also preparing a major treatise on his scientific observations and mechanical inventions. It was to be divided into a number of sections or «Books», Leonardo leaving some instructions as to how they were to be ordered. Many sections of it appear in his notebooks.

These pages deal with scientific subjects generally but also specifically as they touch upon the creation of artworks. In relating to art, this is not science that is dependent upon experimentation or the testing of theories. It deals with detailed observation, particularly the observation of the natural world, and includes a great deal about the visual effects of light on different natural substances such as foliage.[6]

Leonardo wrote:

Begun at Florence, in the house of Piero di Braccio Martelli, on the 22nd day of March 1508. And this is to be a collection without order, taken from many papers which I have copied here, hoping to arrange them later each in its place, according to the subjects of which they may treat. But I believe that before I am at the end of this [task] I shall have to repeat the same things several times; for which, O reader! do not blame me, for the subjects are many and memory cannot retain them [all] and say: ‘I will not write this because I wrote it before.’ And if I wished to avoid falling into this fault, it would be necessary in every case when I wanted to copy [a passage] that, not to repeat myself, I should read over all that had gone before; and all the more since the intervals are long between one time of writing and the next.[6]

Natural science[edit]

Study of the graduations of light and shade on a sphere (chiaroscuro).

Light[edit]

Leonardo wrote:

The lights which may illuminate opaque bodies are of 4 kinds. These are; diffused light as that of the atmosphere; And Direct, as that of the sun; The third is Reflected light; and there is a 4th which is that which passes through [translucent] bodies, as linen or paper etc.[6]

For an artist working in the 15th century, some study of the nature of light was essential. It was by the effective painting of light falling on a surface that modelling, or a three-dimensional appearance was to be achieved in a two-dimensional medium. It was also well understood by artists like Leonardo’s teacher, Verrocchio, that an appearance of space and distance could be achieved in a background landscape by painting in tones that were less in contrast and colors that were less bright than in the foreground of the painting. The effects of light on solids were achieved by trial and error, since few artists except Piero della Francesca actually had accurate scientific knowledge of the subject.

At the time when Leonardo commenced painting, it was unusual for figures to be painted with extreme contrast of light and shade. Faces, in particular, were shadowed in a manner that was bland and maintained all the features and contours clearly visible. Leonardo broke with this.

In the painting generally titled The Lady with an Ermine (about 1483) he sets the figure diagonally to the picture space and turns her head so that her face is almost parallel to her nearer shoulder. The back of her head and the further shoulder are deeply shadowed. Around the ovoid solid of her head and across her breast and hand the light is diffused in such a way that the distance and position of the light in relation to the figure can be calculated.

Leonardo’s treatment of light in paintings such as The Virgin of the Rocks and the Mona Lisa was to change forever the way in which artists perceived light and used it in their paintings. Of all Leonardo’s scientific legacies, this is probably the one that had the most immediate and noticeable effect.

Human anatomy[edit]

Leonardo wrote:

…to obtain a true and perfect knowledge … I have dissected more than ten human bodies, destroying all the other members, and removing the very minutest particles of the flesh by which these veins are surrounded, … and as one single body would not last so long, since it was necessary to proceed with several bodies by degrees, until I came to an end and had a complete knowledge; this I repeated twice, to learn the differences…[6]

Study of the proportions of the head.

Topographic anatomy[edit]

Leonardo began the formal study of the topographical anatomy of the human body when apprenticed to Andrea del Verrocchio. As a student he would have been taught to draw the human body from life, to memorize the muscles, tendons and visible subcutaneous structure and to familiarise himself with the mechanics of the various parts of the skeletal and muscular structure. It was common workshop practice to have plaster casts of parts of the human anatomy available for students to study and draw.

If, as is thought to be the case, Leonardo painted the torso and arms of Christ in The Baptism of Christ on which he famously collaborated with his master Verrocchio, then his understanding of topographical anatomy had surpassed that of his master at an early age as can be seen by a comparison of the arms of Christ with those of John the Baptist in the same painting.

In the 1490s he wrote about demonstrating muscles and sinews to students: